The Camino might be over for this year, but the adventure certainly isn’t. Before my flight back home tomorrow, one last challenge remained: to scale Monte Santiago and lay eyes upon Spain’s highest waterfall, the Salto del Nervión. Since I’m staying in Bilbao, which straddles the Nervión on its journey to the sea, it seemed only natural to go in search of its source. The fact that it springs from a mountain bearing the same name as the patron saint of the Camino clinched it. So, just after eight o’clock this morning, I grabbed my rucksack and poncho (just in case) and set off for the Bilbao-Arando train station.

Leaving the stained-glass masterpiece of Bilbao-Arando behind, I took the 8.25 to Orduña on the C3 line. It’s the furthest stop on the Cercanías line and the trains were running very consistently even through the holiday season, so I was pretty confident about getting there and back OK.

Orduña itself was just waking up when the train pulled in. I made a quick detour via an AlCampo mini-market to grab a picnic lunch: the usual fare of semicurado cheese, chorizo slices and a fresh loaf of bread, with a punnet of grapes to boot. I then doubled back, crossed the bridge over the railway and started to climb up into the hills.

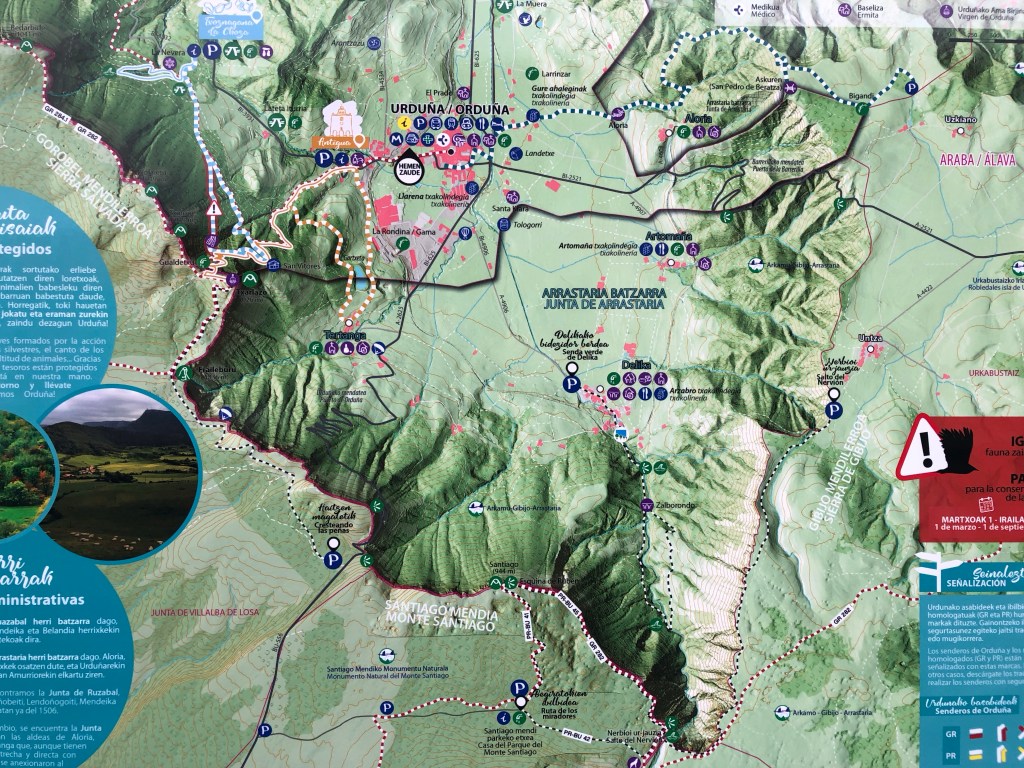

Fortunately for me, somebody had the peace of mind to leave a clearly-labelled map outside the train station. I’d found a few maps online, but I was relieved to find a more reliable one at the start of the trail, so I snapped a photo and used it as my map for the day. I can’t find it online, so here’s a copy if you’re interested:

First things first: the climb was bloody steep. Easy to follow, but steep. And before long, I’d climbed up beyond the cloud level and was weaving in and out of the mist. Sometimes I couldn’t see more than ten metres or so ahead, and sometimes the road seemed to stretch on forever up the mountainside. A jay screeched at me from the base to the summit, and while it may well have been a number of them, I had the strange feeling it was the same bird watching my slow progress. And yet, whenever I tried to lock eyes upon it, I only ever caught a disappearing shadow between the trees.

In the deep woods of the Basque Country, when the clouds are at ground level, it’s easy to see how myths of the Basajaun – wild men of the woods – persisted for so long. God only knows what was watching me unseen in the mist.

I only met two other souls on the road coming down: a local man with a hiking pole in hand about halfway up and a jogger leaving the forest, which would imply he’d just run down the mountain. There’s a reason the Basques have a formidable reputation.

Near the summit, a spring of crystal clear water was a welcome find. I couldn’t help remembering a childhood memory of vomiting for days after drinking from a village spring in the Alpujarras, but the water looked so clean I couldn’t help myself. It was easily the most delicious water I’ve had out here – mountain water always is, if you can get it – though I was sane enough not to use the metal cup chained to the rock, which looked in dire need of a good clean. In a nearby tank, filled to the brim with the spotless spring water, a few tiny newt efts were swimming about.

After what felt like an age (but in reality only took ten minutes over an hour) the track suddenly came to a narrow crevasse which cut a path through the karst to the clifftop. With one last screech from the jay echoing after me, I put the cloud forest behind me, pushed the metal gate open and stepped out of the Basque Country and back into Castilla.

At first, the rolling clouds shrouded all but the peak upon which I was standing from view. I could just about make out the bizarre sculpture to an apparition of the Virgin Mary in the form of a colossal concrete block supported by a stylised tree looming out of the mist, but it looked like it had been fenced off and graffitied for good measure long ago.

More impressive by far was what I could see when I turned around. The Castilian sun began to beat down through the clouds, and suddenly the sheer majesty of the Sierra Sálvada began to unroll before me like a painting. I was lost for words. Pictures don’t do it justice, but they might bring you closer to that wonder I witnessed.

The breathtaking crags of the Sierra Sálvada give an indication of what to expect from the Salto del Nervión long before you reach it. It’s a drop of more than 200m to the bottom in places, and even the thought of kicking a pebble over the edge is enough to tie your stomach in several uncomfortable knots.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m absolutely mad about mountains. But there’s nothing funny about a drop of that height, particularly when it isn’t broken by any tree or slope on the way down.

Ironically, perhaps, some of Spain’s biggest creatures are perfectly at home here. The hulking shape of the griffon vulture was rarely out of sight during my wanderings along the clifftop, but nowhere more so than about the stark stack known as the Fraileburu – the Friar’s Head – an utterly unassailable column where many of the Sierra’s griffons had chosen to roost, haughtily observing the valley below. I haven’t needed my camera once on this holiday – my phone has done a more than satisfactory job – but I was missing it then more than ever. A decent telephoto could have worked wonders on the griffons riding the thermals below, as well as pulling the acrobatic choughs and the few pairs of Egyptian vultures into focus for good measure. Instead you’ll just have to see how many you can spot clinging to the cliff face below.

From the summit of Monte Santiago, it’s a fair trek to the Salto del Nervión. I didn’t stop often and I keep a pretty merciless pace, but it still took me the better part of two hours to reach the waterfall. Fortunately, the path cuts through tree cover for a large stretch, and the views are incredible – especially so as the sun had burned off most of the mist by this point, offering spectacular views down to Orduña, now some way in the distance.

The Mirador at the Salto was quite busy by the time I arrived (around one o’clock) but one look was enough. The river was bone dry: I might have guessed from the absence of any sound of crashing water. So much for the highest waterfall in Spain! It seems it’s only really in action after heavy rain, otherwise the Nervión is supplied by a network of underground rivers that ensure it flows year-round, while its primary spring in neighbouring Castilla has a tendency of drying up in all but the wettest seasons.

Still – box ticked, I suppose.

Perhaps more interesting than a dry waterfall is the nearby lobera, an ancient wolf trap built possibly over two thousand years ago by the ancient Basques to hunt wolves and other large game on the clifftop. In a fashion akin to the Native American buffalo jumps, the wolf would be chased into a funnel, with men beating drums on one side and the cliff on the other, driving the poor beast into a deep pit at the end of the funnel as its only escape.

I didn’t see any wolves during the hike, though they have been seen recently in the area after a long absence. Instead I disturbed an amorous couple who had straddled the large wolf statue and were enjoying each other’s company, though they had picked an exceedingly odd place: I can think of better spots for a tryst than the site of a Neolithic abattoir.

From the Salto del Nervión, I decided to fork east and descend back into the valley of Orduña that way. The trouble was, the map – which had been utterly brilliant thus far – was pretty dismal about suggesting a way back down bar turning around and heading back the way I came. One of the maps I’d found online seemed to indicate a track that led down through the forest an hour or so to the north of the Salto, but I couldn’t find anything like it. Scanning the east side of the valley during the hike didn’t show much either, beyond what might have been a dry river gulley running down the mountainside.

In the end, rather than face a possibly two or three-hour march to the north, I decided to follow the beginnings of a track that appeared as the cliff began to slope rather than drop. Whether it was made by man or beast I’m not entirely sure, only that it probably wasn’t the track suggested online and that it very quickly came to an end.

There are few things more frustrating than getting halfway down a mountain and realising you’ve lost the path. At least you can surrender going up, but on the descent, you have no choice but to find a way down somehow. So I did what I have done in the past, foolhardy though it seems, and cut across country.

This is a lot easier said than done when the cross country in question is a forest thick with underbrush that happens to be growing on the side of a mountain. The ground under my feet was not always stable, there were thorns everywhere and the animals tracks I was following – boar, I wouldn’t wonder – were not always reliable. The heat of the midday sun was similarly unwelcome, silencing the forest and making my every step sound like a cannon. The vultures circling overhead only added to the dismal state of affairs.

Twice I came upon what looked like a road, but rather than wind up on some local farmer’s turf (and potentially ending up in really cross country) I decided to stick to a personal motto (don’t ever, under any circumstances, f*ck with the Basques) and continue to forge my own path.

It took just over an hour to escape the forest. I don’t think I’ve been more relieved to see a tarmac road in years.

I made it back to Orduña’s train station with seven minutes to spare before the 16.45 train back to Bilbao. I must have looked a beardy, sweaty mess but I was past caring. Despite the mountain’s best efforts, I’d made it back in one piece.

My old English teacher once told me you can’t claim to conquer a mountain, a thing which has been standing on this earth since the world was young and will be there long after you have gone. I’m still hooked on the idea of climbing higher than the vultures – there are few things in this world more awe-inspiring than looking down on creatures that are usually specks in the great blue beyond – but I’ll hand it to him here. Mountains are ancient, treacherous things that deserve to be treated with respect.

I finished my time in Spain by summiting Santiago’s mountain, but the mountain very nearly got the better of me on the way down. A knock to my hubris – and a necessary one.

I’ll stick to regular cross country around the school grounds for now. I’ve had quite enough wayfaring for one holiday! BB x