Albergue de Peregrinos, Grado. 21.40.

Confession. I was genuinely considering skipping Grado to gain a day this morning. I think I still hadn’t shaken the idea that, if I could only walk a little faster, I might catch up to my companions on the Camino Francés before they left for home. But the Camino, like an old god, is fickle. I’m not sure whose idea it was – Santiago, the Lady of El Rocío or the capricious spirit of the Camino itself – but I was waylaid at the albergue this morning by a retired Swedish woman who wanted company on the road out of town. The Camino leads straight to the train station, and I might have made it in time… but the Swedish woman pointed left and I followed without thinking.

I lost her about half an hour later when I picked up speed at the city’s outer limits, but I see now that it was a signal: no tricks this time. This Camino must be walked from beginning to end. There is something along this road that I am meant to do or see. The fatalist in me takes over on the Camino, and right now he is utterly convinced of that fact. So here we are.

Welcome to the Camino Primitivo. If you were expecting something similar to the Camino Francés, think again. It’s almost like stepping out of a bus and onto a boat: the same feeling of companionship, but an altogether different vehicle in an altogether different environment.

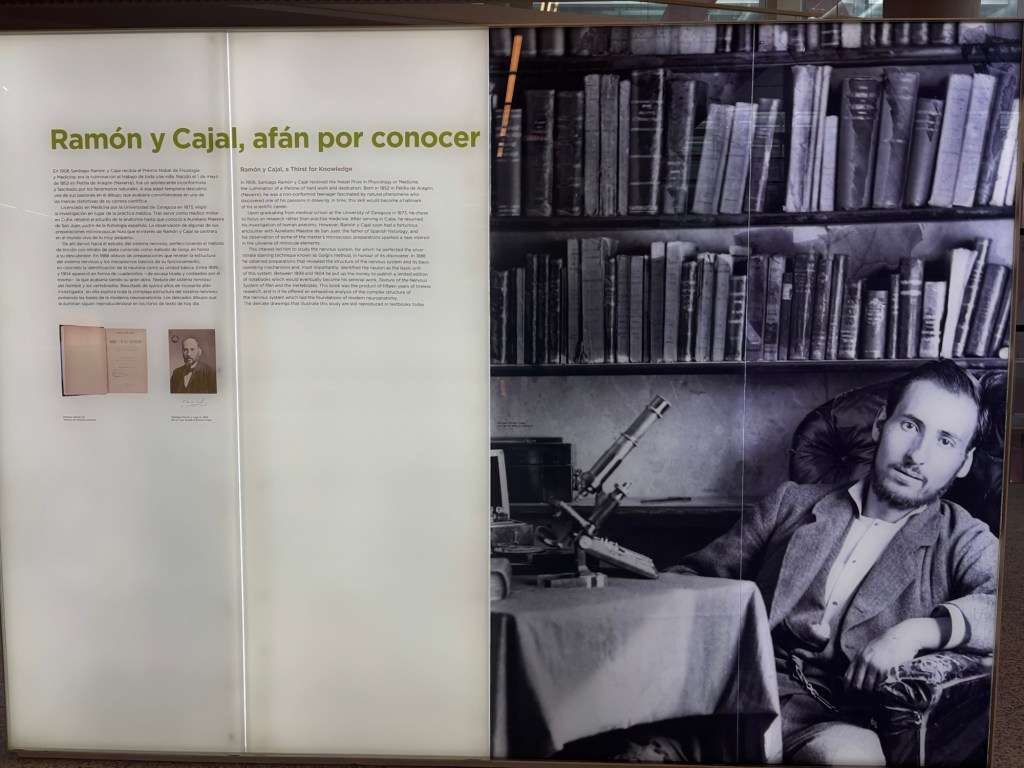

Asturias is, in a way, the grandfather of Spain. This green and clouded region, together with Cantabria and the Basque Country, was the final holdout of Iberia’s Christians during the Moorish invasion of 711, and it was from here – so the legends tell – that Don Pelayo established the Asturian monarchy, the earliest forerunner of the Spanish crown, and began the Christian reconquest of Spain – the Reconquista – which would take nearly eight hundred years to complete.

You might think such a place would be as Spanish as it gets. You would be mistaken. This is not a land of paella, flamenco and bull-fighting, or dark-skinned maidens flanked by guitar-wielding lotharios (a stereotype far more common among Italian pilgrims this year). This is a green and hilly country where the clouds descend as far as the tree-tops and sometimes beyond; where the rain rolls in off the sea in visible eddies and falls like mist on your face. Where the men are short but powerfully built, and the women breathtakingly pale. Where great clouds of smoke rise from the quarries and factories, and the air is thick with the constant ringing of cowbells. This is Asturias. It could hardly be more different to neighbouring León. It is a reminder – as though one were needed – that Spain is, in reality, a multinational state, where even the kingdom that started it all has its own distinct language and identity.

For the greater part of the morning, my road was cushioned by the clouds. Sometimes they moved with me, sometimes they moved against me. It rained for a half-hour or so, but it was not so much rain as a rain cloud that was so low to the ground that one could walk right through it. The Camino from Oviedo ducks and weaves through the hill country, sometimes following the asphalt roads, sometimes leading down dark trails into the tangled forests of oak and eucalyptus.

It’s very easy to see how this corner of Spain – behind the frontier of the Cordillera Cantábrica – shelters most of Spain’s lingering mythology. The forests are dark and watchful and the mist rolling through them plays tricks with your eyes. I heard something large kick up the leaves and dart into the deep at one point, but I never did see what it was. A deer, perhaps. There are plenty of them about.

In one of the forested stretches, the Camino crosses a small clearing scarred with limestone teeth, like the bones of some ancient monster. A splash of colour on one of the rocks nearest to the road caught my eye and, on closer inspection, it was the head of one of the spirits the Lady of El Rocío sent to guide me yesterday: an Egyptian vulture.

Egyptian vultures are one of the oldest species of vulture still in existence. They are also the last of their kind, with their nearest relatives believed to have died out during the Miocene. They are incredibly intelligent creatures, being one of the few species to use not just one but two tools: using stones as hammers to break into eggs, and sticks as spools to gather wool or other nest-building materials.

They’re also amazing to look at, with their glam-rocker hairstyles and their black and white wings. I found myself wondering whether this bird was one of the inspirations for the Chozo, an ancient race of superintelligent avianoid aliens from the Metroid series. Their faces certainly match up to the earlier designs.

Well, while I had them on the brain, suddenly, there they were: a pair of them, circling low over a hamlet on the outskirts of Premoño. A local and his son were heaping refuse onto a small bonfire, which may be what drew them in, but before long they were riding the thermals high into the sky. It was enough to make me skip one breakfast stop just to chase after them and watch them ride higher and higher until I could no longer make out the diamond shape of their tailfeathers.

I tried to make amends on a breakfast stop in Valduno, but one of the waiters made frantic signs to be quiet as I opened the door: half the bar space had been given over to microphones and speakers, and they were in the middle of recording a podcast. I could get some water, they said, or wait in a corner. I felt I was intruding on something. I moved on.

I found a better spot in Paladín, where I had a nice long chat with the barman. He had some sort of alarm setup which sounded awfully close to Colours of the Wind from Disney’s Pocahontas, which went off whenever somebody walked through the gate – I guess that’s how he knew to appear the moment I arrived. He was keen to know how many pilgrims I had seen on the road. I told him only a handful, as I had been one of the first to leave Oviedo – which was true – but that there had been plenty at the albergue. He was quick to point out that not all of them would come this way, as the Camino Norte also runs through Oviedo, but seemed very appreciative to have a conversation with a peregrino. Spanish tourists bring money during the summer, he said, but they don’t bring much more than that: a place to eat and sleep and then they’re gone. He missed conversations with pilgrims and swapping tales from the road.

After Paladín, the Camino returns to the banks of the Nalón for a little while. I was so fixated on the beauty of the river that I almost stepped on a stag beetle. I have yet to see one of the impressive males, but the females seem to get about quite a bit during the day, as this is the sixth or seventh one I’ve seen along the Camino.

Like its sister, the Tajo, and a great number of other Spanish rivers and creeks, the Nalón cuts right through the craggy cliffs and sierras on its winding journey to the sea. The train from Oviedo seems to follow it, which must make for a spectacular journey. There’s a small bar at the foot of the Peñón de Peñaflor where you can stop for a drink, but I was much too busy drinking in the view. The old masters painted paradise as a garden with many mirrored lakes and fruit trees, but I think mine would be scarred with karstic crags just like these.

After crossing the river and the tiny settlement of Peñaflor – a small cluster of houses that seem to exist purely to justify the train station – the Camino cuts across the countryside toward the hill town of Grado. A local girl in white cut-off jeans stepped out into the road as I left town and sauntered on ahead with a jaunty, confident stride, toying with her hair over one shoulder and then the other, and then held up in one hand, as though she couldn’t quite make up her mind how she wanted it. It was about half an hour’s walk to Grado, where she finally disappeared into one of the apartment buildings. Spaniards aren’t known for being natural long-distance walkers, so I wonder what she was doing out here?

I reached the albergue a full two hours ahead of opening time, so I took off my sandals and zoned out for a bit. I’ve found a comfortable method in wearing my liner socks underneath the woolen socks (which may well be their original purpose). It’s not too hot and it meant no discomfort whatsoever from my blisters. Let’s see if it lasts.

Andrés, the cheery hospitalero from Badajoz (I’d recognise that accent anywhere) arrived just before 2pm and handled check-in, after which I had a good nap for two hours (that’s how I can justify still writing at this late hour, when all the other pilgrims have long since turned in). I considered going out to eat, but instead sorted out my flight home and popped out to a supermarket to get some supplies – namely, sun-tan lotion, as I’m all out and there are some long days ahead.

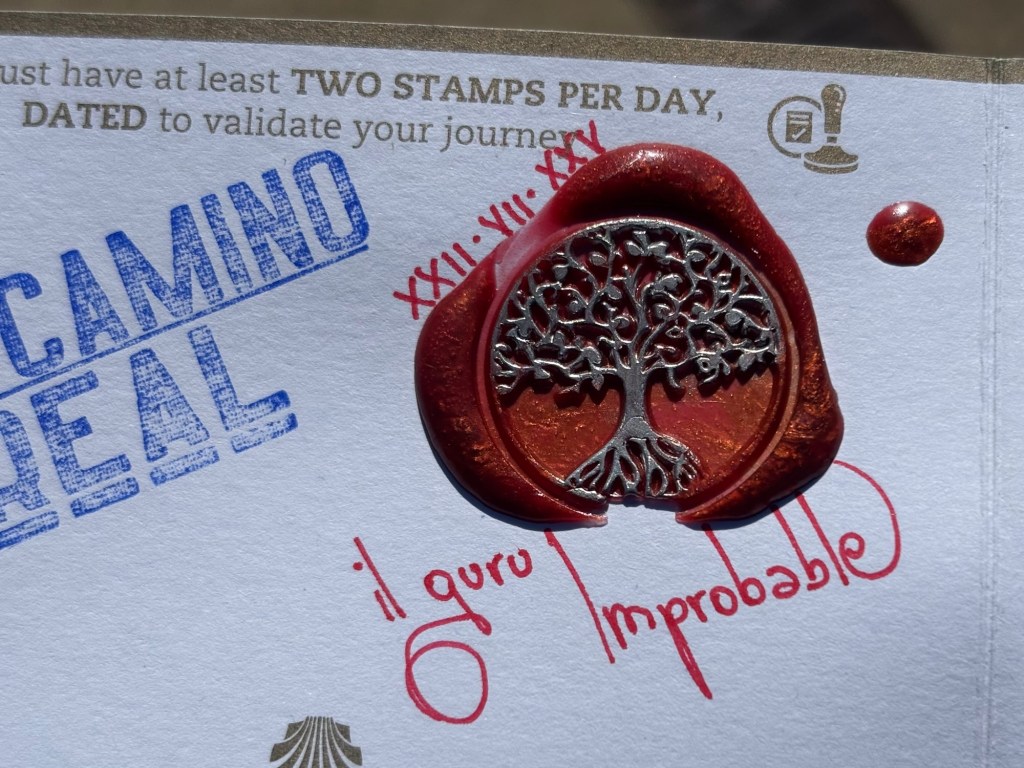

Back at the albergue, Andrés suggested making some wax stamps. This slowly brought all the pilgrims downstairs and got conversations flowing all around the room. Hospitaleros only typically work for around 15 days before moving on, but here was a master at work: friendly, accommodating, knowledgeable and unimposing. Just present.

He also had the spirit to call out a fellow Spaniard for a slightly tactless remark about how “easily” Moroccan migrants get Spanish citizenship. As a former civil servant, Andrés certainly knew his stuff – enough to put the man in his place with some hard facts about the reality of immigration policy in Spain.

I feel I learned a lot today. I also got a shiny new wax stamp for the passport, which I painted gold in a nod to the Asturian flag. Now when I look at it, I’ll remember this place.

I don’t know if I’ll find a “Camino family” again like I did on the Francés – that road does facilitate the group dynamic like no other. But this feels right. I’m learning so much and seeing so much more.

Somebody stopped me from catching that train, and they had the right of it. Here’s to another week and a half of wonder. BB x