Cafetería La Concha, Grañón. 16.15.

A red sky in the morning is usually a herald of rain. I saw the rising sun for just a fraction of a minute as I left Nájera: a huge blood-red disk, perfectly circular, disappearing almost as soon as it appeared behind a low curtain of cloud that stretched at least as far as Aragón, and perhaps beyond. It’s certainly true that it was a cooler and cloudier morning than most, but whatever promise of rain the sun made it the early hours was forgotten once it was out of sight, like a fickle lover. The clouds have almost entirely disappeared, leaving behind the immense blue heavens for which Spain is so famous.

I’m here in Grañón – ice cream in hand – and it couldn’t have worked out for the better.

I was woken in the night by a pillow to the face. In the half-light I saw the pilgrim on the bunk below standing there. He said something, but it was in German and I was half-asleep, so I neither understood nor recall what he said. I guess I might have been snoring, though that’s not usually a problem these days – but I was on the top bunk, which had no railings, so my sleeping posture probably wasn’t the best last night.

The others – my Camino family, as it were – were all still fast asleep, and their intention was to reach Santo Domingo de la Calzada (the guidebooks do have a strong hand in where pilgrims end up), so I set out alone. I have somewhat mastered the “Irish Exit” strategy, and the Camino lends itself very well to such a move.

The reward for striking out alone was a nightjar – and not just the sound of one, but the sight of one as well. They’re bizarre creatures, nightjars: shaped like a cuckoo, or maybe a small hawk, with an owl-like face, a whispered beak and enormous black eyes. They’re often heard in the places they frequent, but rarely seen due to their nocturnal habits, so it’s remarkable that they should have left such an impression as to have such an intensely evocative name in each language.

In German they’re nachtschwalben – night swallows. In Spanish, chotacabras – goat-suckers (the Italian succiacapre is much the same). The French use the term engoulevent – literally, wind-eater, on account of their hunting habit of flying through the twilight air with their beaks wide open. In English, I can only assume the name is phonic: because the nightjar’s call can only be described as a long, rasping jar or churr, which it can go on producing for hours with seemingly no need to rest.

I only saw it a few times as it moved beneath the forest canopy, with the jerky motion of a child’s toy glider, its wings held high as it manoeuvred dextrously through the trees. But it was enough. I consider that a very good start to the day.

I came this way during the spring a few years ago and I remember needing gloves, it was so cold. There was even frost on the ground. Not so today: the endless green fields of shimmering wheat have since turned to gold, as though by the hand of Midas. With the merciful cover of the clouds, they were not blinding to the eye, so the loss of my sunglasses in Sansol the other day was no concern, though I did buy a new pair in Santo Domingo; it would be nothing short of madness to attempt the ceaseless flat of the Meseta without them (where it sometimes feels like you’re walking on the sky).

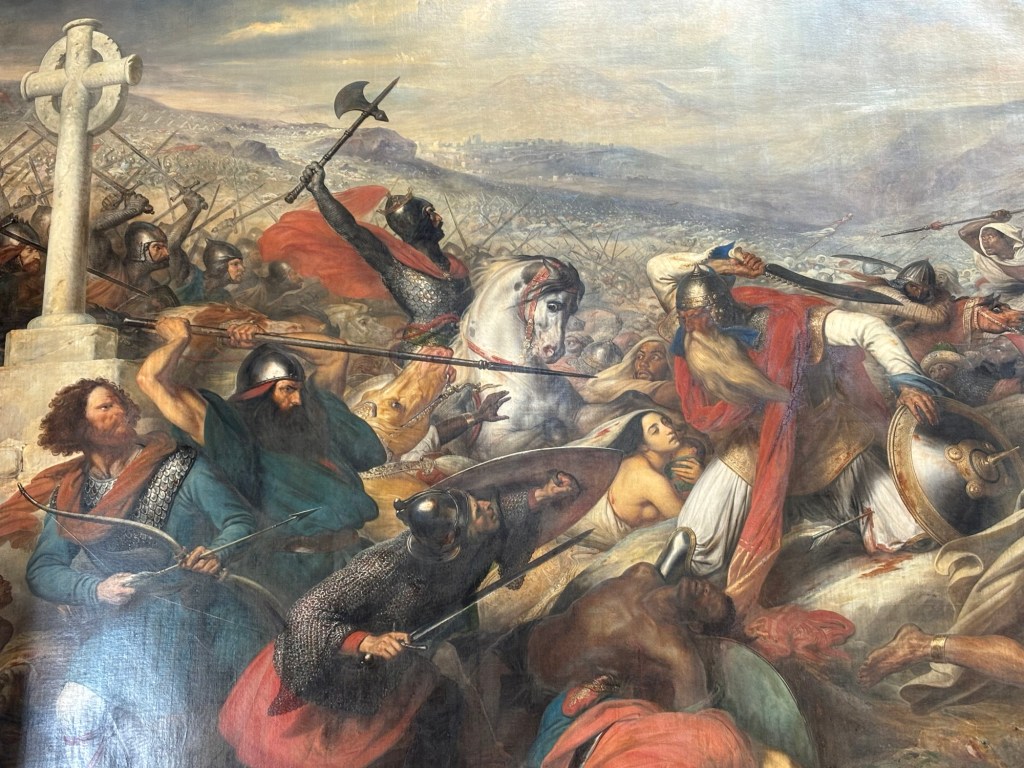

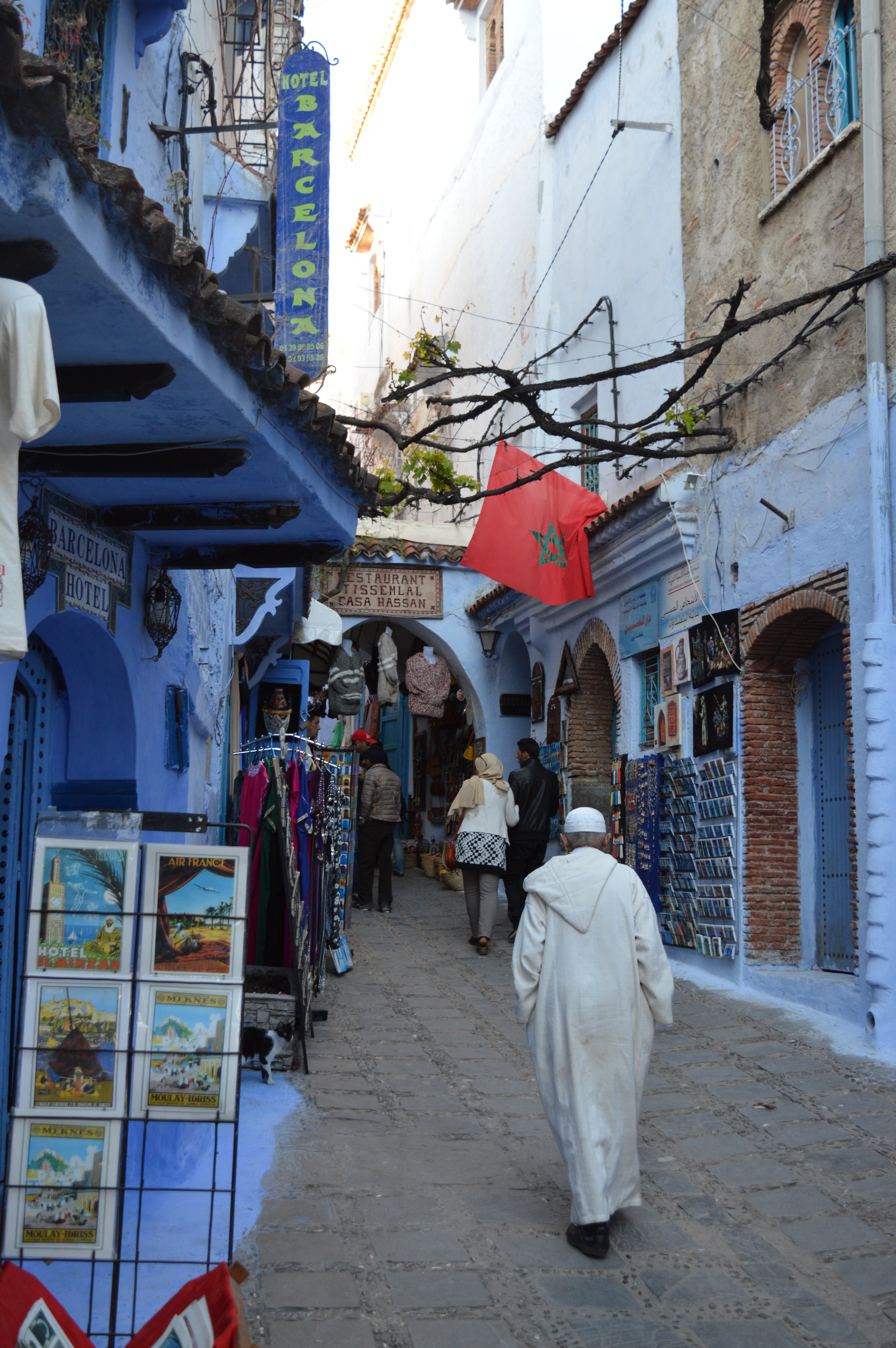

I stopped in Santo Domingo to have the rest of the pâté and bread I bought yesterday as a light lunch. The last time I came here, I was with Mikkel, Lachlan and Sophia and so I never got around to visiting the cathedral, so I made good on that today. Apart from netting me another couple of stamps for the credencial, it also housed a number of treasures that I wanted to investigate – not least of all the famous “resurrected chickens” that feature so prominently in the town’s history.

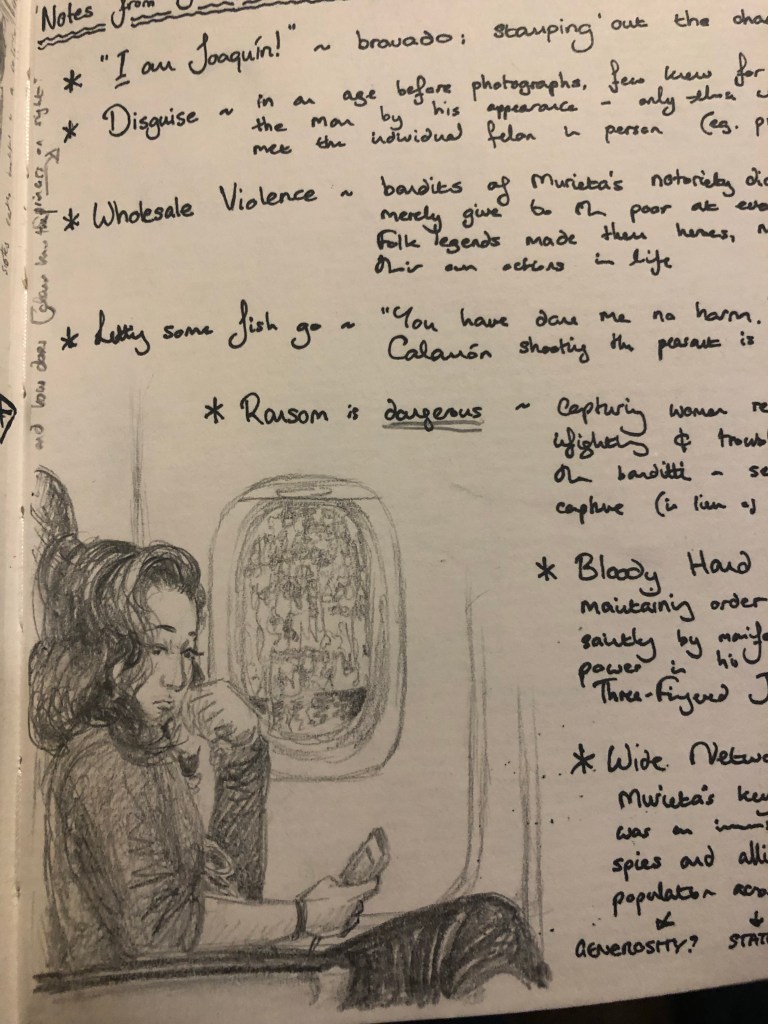

Santo Domingo de la Calzada, like so many towns along the Camino, was born on the pilgrim road, founded by the same Domingo García who gave the town its name. Its most famous legend tells of the execution of a young German pilgrim who, passing through the town, attracted the attention of the mesonera (innkeeper). After rejecting her amorous advances, the spiteful mesonera concealed a silver cup in the pilgrim’s bag before he left, for which he was accused of theft, sentenced to death and hanged on the spot. When his parents came to identify the body, they found him alive, claiming Santo Domingo had saved him. The sceptical mayor, who was fairly sure that the boy they had hanged the day before had been executed properly, claimed he was as alive as the chicken on his plate – which promptly stood up and crowed, testifying to the truth of the pilgrim’s fate.

Ever since, a pair of the descendants of the resurrected chickens (don’t ask me how they check) have been kept in the cathedral, together with a piece of the scaffold where they hanged – or tried to hang – the innocent pilgrim, all those centuries ago. Go figure.

Santo Domingo’s cathedral, like many in Spain, is full of hidden treasures. I was particularly taken – as always – by the mythical creatures that pop up in the stonemasonry. Harpies, dragons, demons, griffins… for a faith that spent so much time and money driving all traces of paganism from the land, it sure is amusing to see that Spain’s churches are full to the rafters – quite literally – with frozen memories of that dark world.

One really stands out, especially after some recent reading. In one alcove, an icon of the Virgin Mary and child stands above the carved image of a griffin – in fact, there’s quite a few griffins watching over the chapel from the surrounding pillars. There’s a deeper poignancy at work here: griffins have been symbols of maternity since their invention over a thousand years ago.

Unlike the other mythological beasts of the ancient world, like centaurs, unicorns and minotaurs – which have a solid grounding in Greek mythology – the griffin seems to spring into existence out of nowhere, but already fully-formed.

Adrienne Mayor has a very convincing theory that the griffin is an unmistakeable reimagining of the protoceratops, a Cretaceous era dinosaur often found protecting its young in the lands where griffins were believed to reside (Central Asia). As stories of such “griffins” reached Europe, they entered our heraldic system, and are often to be found around the Virgin Mary, the single most important symbol of maternity in the Christian faith. A seemingly bizarre pairing – but a perfectly logical one. Two ancient beliefs meeting in the middle.

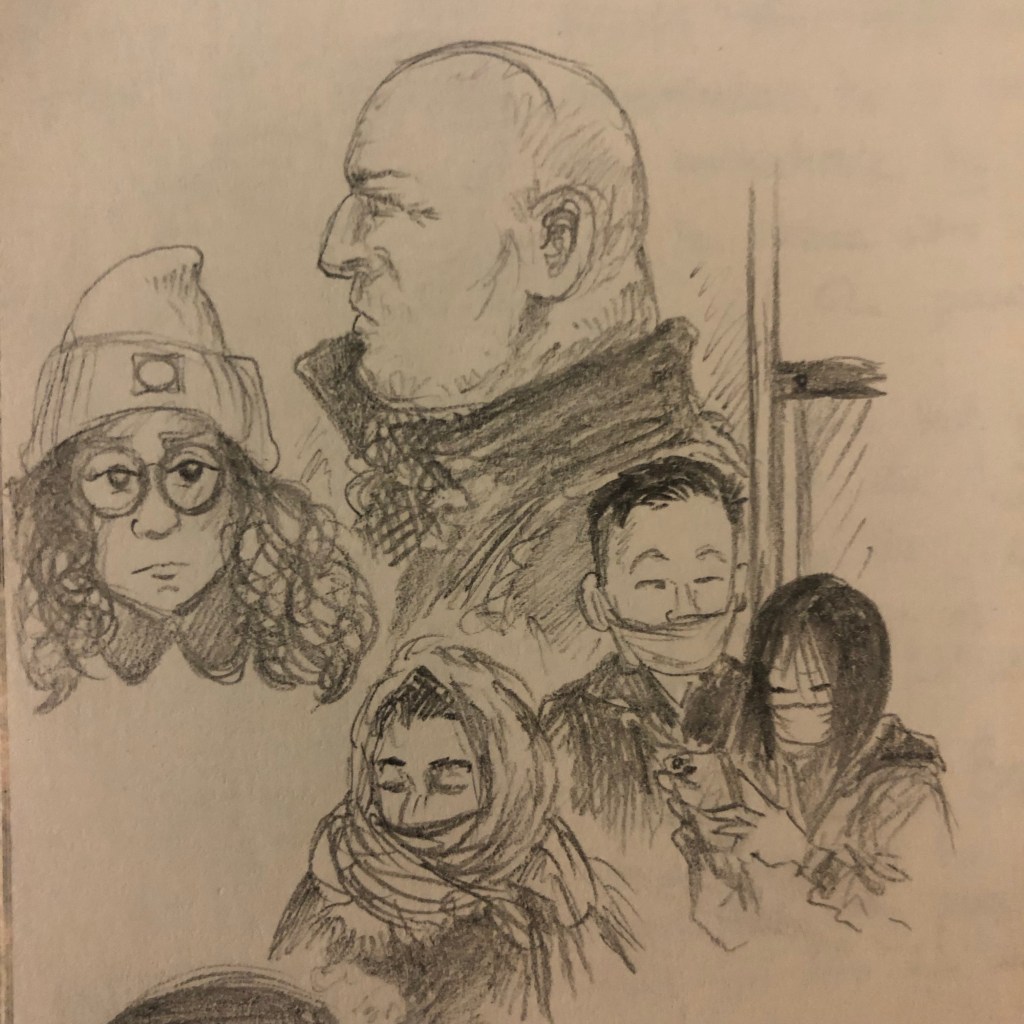

Under the cathedral, where Santo Domingo is buried, a relatively recent mosaic stares out at you from a thousand shining tiles. The design is modern, but the style is almost Byzantine: teardrop-shaped faces line the wall with huge, almond eyes the colour of midnight.

This is the kind of religious art that I have always found especially compelling. There’s an otherworldliness to it that borders on the mystical, a connection to the faith of those first believers long ago. That’s what I sometimes think the modern church is missing, why so many lose interest: the more it tries to modernise, to catch up to the new generations “on their level”, the more it loses the mystery that made the early church so compelling. I know that for me, at least, it’s that connection to the ancient ways, to tradition, that speaks to me. And I get a piece of that when I see this kind of art, even in imitation. A mirror to the ancient world, when faith was new and hot like a flame.

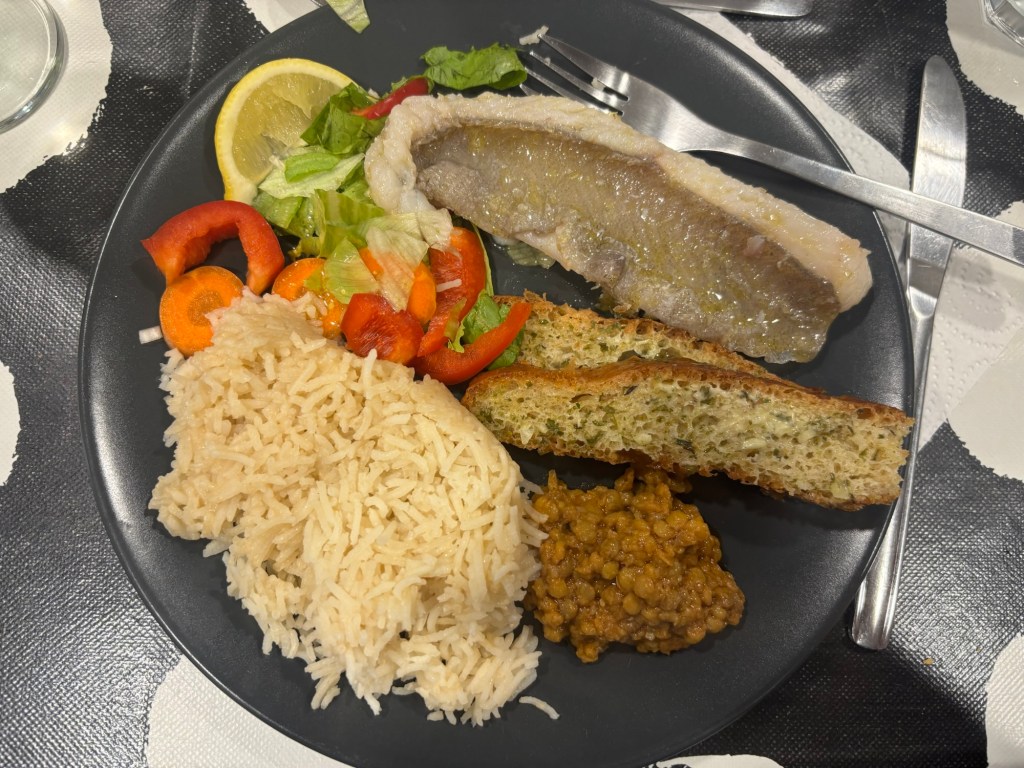

It’s nearly half past five. I’d better head back to the albergue – I’m on dinner duty. That’s the price for arriving early! BB x