They weren’t wrong when they called Rome the Eternal City. It seems to go on forever and ever – which is probably why everybody I asked told me not to walk, but get the bus or metro. But I’m stubborn when it comes to walking – years of not driving forces you to master the art – so I spent today exploring Rome on foot. The only foolish thing was that I did it twice: once to scout the city, then once again to visit the Colosseum for my timed entry slot. My heels are aching and frankly I can’t blame them. But if anything should be aching, it’s my eyes… because there’s more to see in Rome than in any city I’ve ever seen in my life.

I’m staying in a cosy AirBnB behind Castel Sant’Angelo, situated within a condominium that’s just a stone’s throw from the Vatican City. I figured it would be nicer to be in a quieter part of the city as I’m not much of a city boy, and I wasn’t wrong… Rome is loud. Somebody grabbed the volume dial on the train from Venice and ramped it up to max. Noisiest of all are the ambulanzas… the way they hurtle down the streets with sirens blazing every ten minutes you’d think the Romans had one of the highest mortality rates in Europe. Given the Vatican’s population growth rate of 0% and the average age of its citizens, perhaps that’s not surprising.

It’s telling enough that between writing the word ambulanza and this line, I’ve heard four go by in the space of two minutes. Ils sont fous, ces Romains.

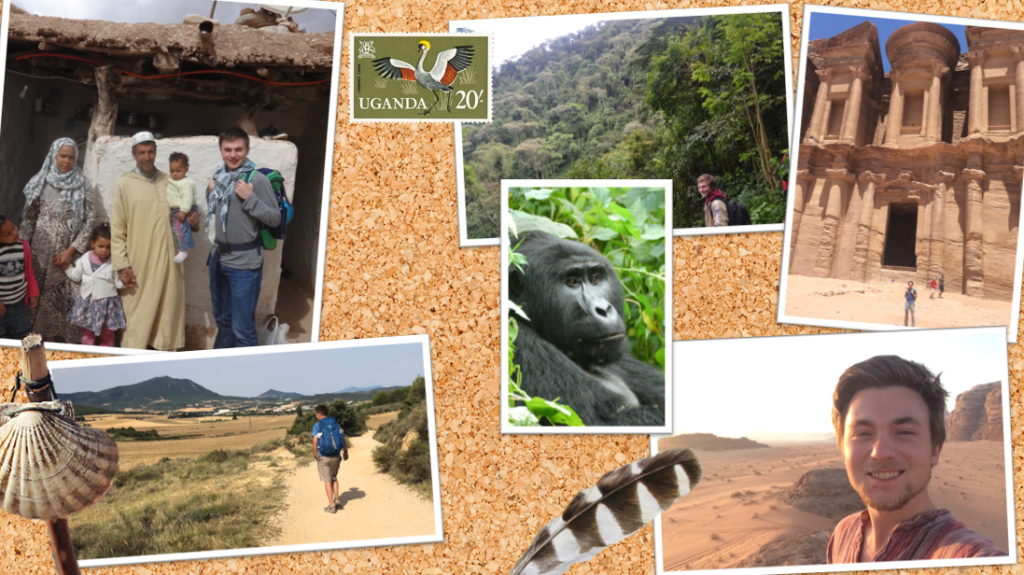

I started my route by crossing the Tiber over the Ponte Sant’Angelo. A Korean couple posed for their wedding photographs on the bridge while two local men dressed as legionnaires did the same with a family of tourists before bullying them for cash. It’s been a long time since I’ve done real tourism – my usual holiday destinations are well off the beaten track – so the vast number of selfie stick sellers, water hawkers and tack touts caught me off guard. They seem to swarm about the oldest parts of the city like flies around a wound, preying especially on the young, the old and the Chinese. For the first time, as a single male traveler, I passed most of them as though invisible. I guess I’m not prime real estate – nor would I have much need of a selfie stick when I’m armed with my trusty Nikon D3200.

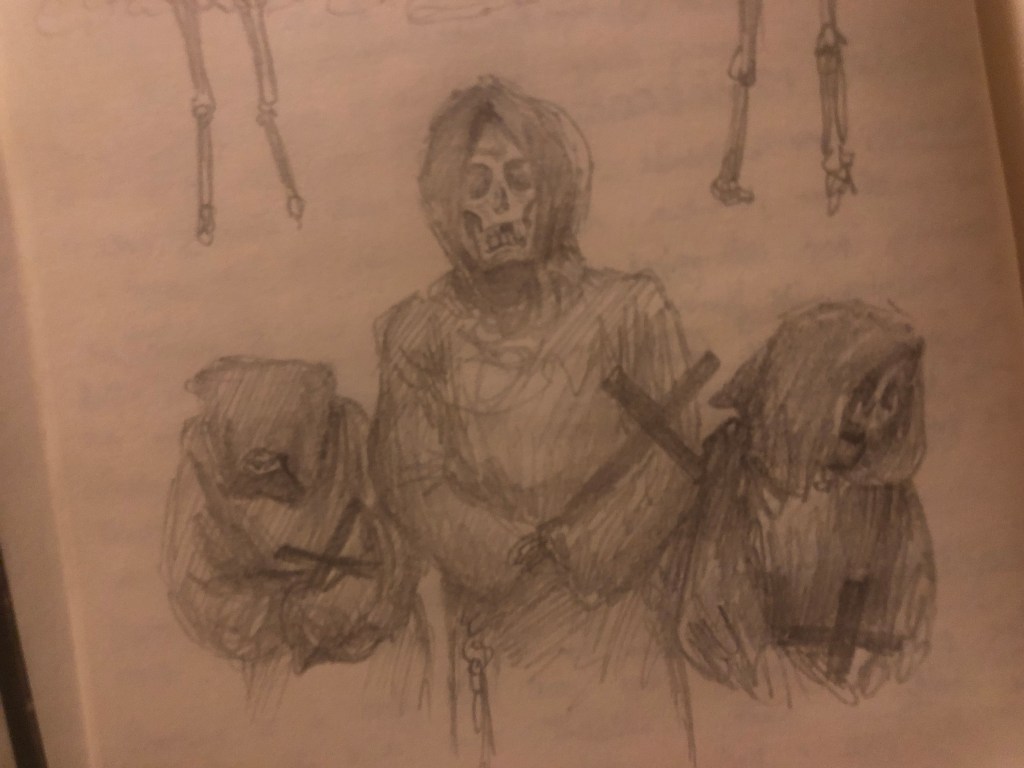

The Pantheon was a little underwhelming on such a cloudy day, so I saved it for later. The famous Trevi Fountain was being cleaned as I walked past, knocking two items off my itinerary early on. Instead, I spent some time in the bizarre Capuchin Crypt to see one of the most alarming sights in Rome: the disinterred and rearranged bones of hundreds of monks, dressed up and set on display in a grisly but remarkably intricate work of art. As a mark of respect to the bodies (which does seem odd when they’ve been played with so) cameras aren’t allowed, but fortunately nobody ever seems to have any issues with sketching, so I spent some time drawing the macabre display instead.

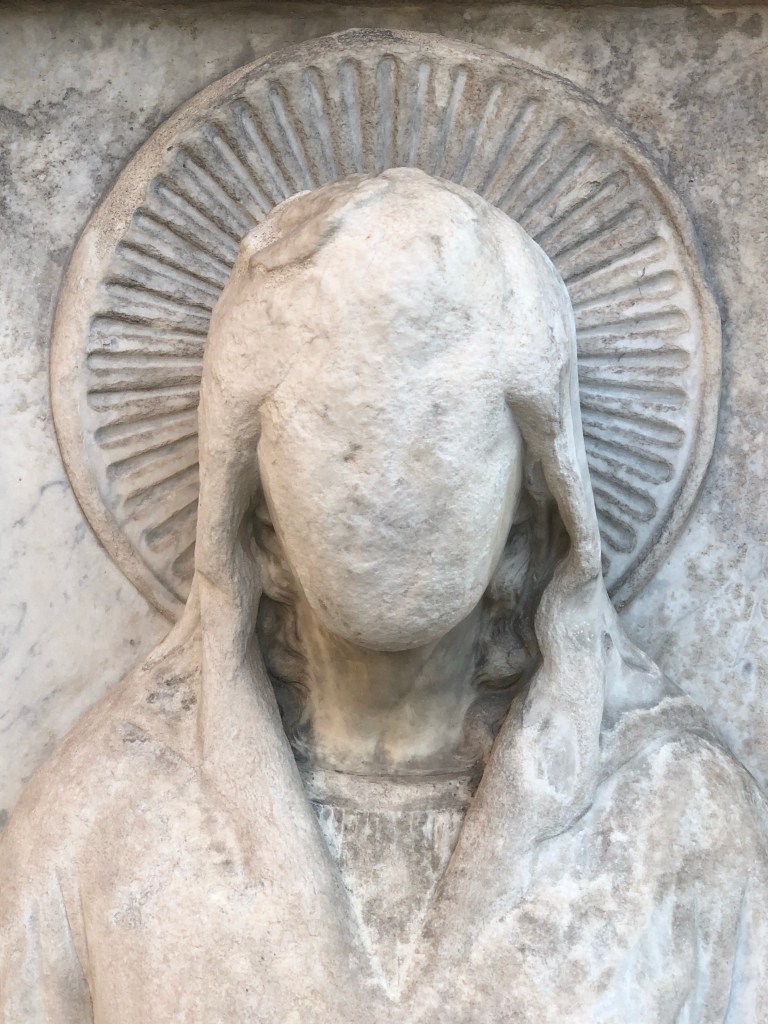

Moving on through the squares and streets, past sharp-dressed polizia and fire-breathing carabinieri, I made a point of dropping in on a couple of Rome’s churches. Not too many – there are so many here one could burn out easily – but enough to get a flavour. Even if you’re not religious in any way, they’re blissful refuges from the constant hubbub of the city.

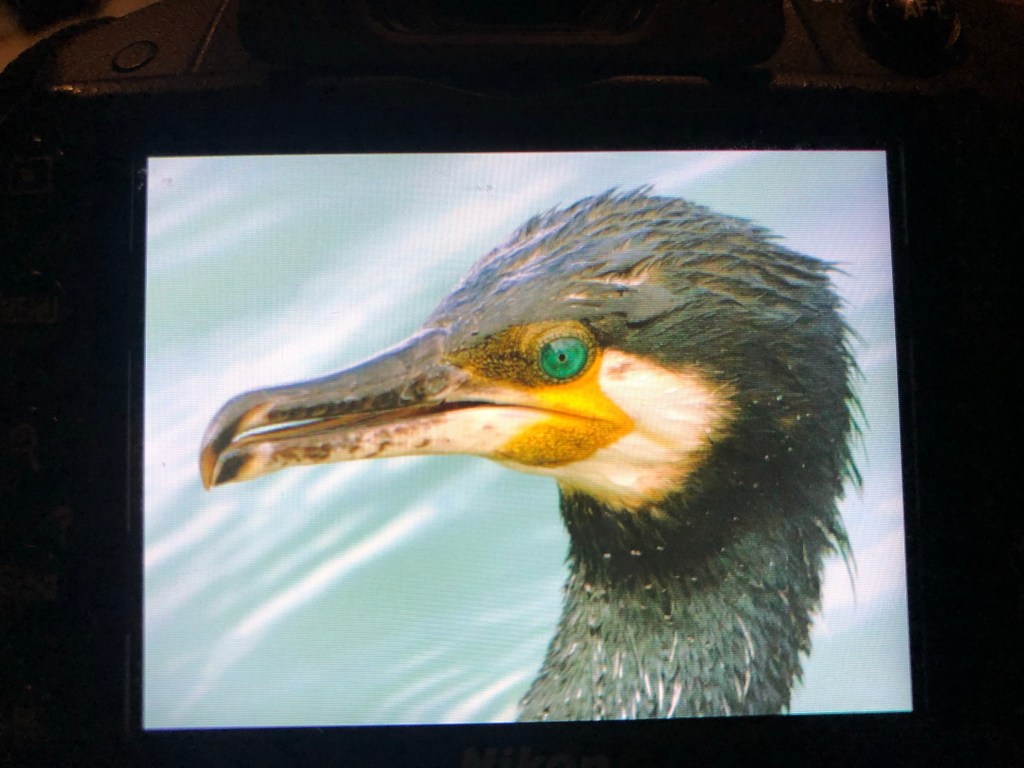

After four days in Venice, the near total lack of traffic along the River Tiber was hard to believe. And not just on the water – its banks too were almost deserted, but for a couple of joggers and a few clusters of homeless folk. Even the usual river fauna was nowhere to be seen… just a motley crew of gulls and a couple of hooded crows. By contrast, the Guadalquivir is usually heaving with both birds and sunseekers. Perhaps Rome is just too busy to afford the Tiber either.

After an all-too brief recharge back at the AirBnB I trekked back across the city toward the forum, where sadly no funny things happened. I made it to the Colosseum in more than enough time and they let me in fifteen minutes early, so I guess the newly imposed time slots are more guidelines than a point of law.

Standing in line, I watched a German family try to take a selfie where they all try to jump at the same time. Ein, zwei, drei! Ein, zwei, drei! A gang of twenty-something-year-olds sauntered by, and one of them who clearly thought himself a first class joker kept jumping into their shots, sauntering off with an unflattering imitation of their countdown. The same thought occurred to me as it had with the phoney legionnaires: some people are just goons for no reason.

The Colosseum… was it worth the entry fee? I think so. It is without doubt one of the most impressive buildings in the world, and though it’s a lot more imposing from the outside, with all the scaffolding and building work going out around it, it’s easier to get an impression of its ridiculous scale from inside these days. They’re currently building a new metro line that will service the old city, which I saw advertised all over today. Great news for my feet, not so great news for the Colosseum, which won’t enjoy the additional underground reverberations.

I did get one thing right today, and that was my timing: the blinding white clouds that covered the city all morning were gone by five o’clock, which meant my walk home through the Forum landed right in the golden hour. Blackbirds and blackcaps sang from the olive trees and the crumbling walls as they must have done since before the Romans came. Children played leapfrog between the pillars. A British Indian family had an argument about “too much history for a holiday”, while a Turkish girl made her boyfriend take her photo again and again and again and again under the wisteria tunnel. My services as a family photographer were called upon three times between Titus’ Arch and the Temple of Saturn, but that’s what you get for obviously wandering about with an SLR camera.

I don’t really have anything profound or original to say about my adventures today, which is a little disappointing. I guess you could say that everything that could be said about Rome has been said by thousands before me. So tomorrow, after a decent rest for my beleaguered feet, I think I’ll investigate somewhere further afield. There’s something very appealing about spending the day in Ostia Antica – not least of all because of the mild amusement I get as a Spaniard from the name alone. But that’s not set in stone. For now, I should get some shut-eye, and give my blistered heels a well-earned break. BB x

P.S. Oh, and I also had my first Italian pizza this evening. It was… OK. Nothing to write home about. Which is ironic, since that’s exactly what I’m doing right here.