2:45pm, 20th March. I’m sitting on a bench on Brighton’s Palace Pier, sheltering for a moment from the wind. A sign in front of me reads “It’s fun all year on Brighton Pier”. Somewhere down the coast to the east, there’s a few mad folk towelling off after a swim. The sea doesn’t exactly look inviting today. I look down through the slats. The bottle green waters of the Channel heave and swell about the centipede legs of the pier below. I wonder what creatures of the deep might be looking back up at me, besides the silent starfish in the silt.

Two men wander over to the parapet, gazing down at the beachgoers below. One of them watches in silence, nodding occasionally. His companion holds a recording device of some kind in his hand and is whistling a crude but not inaccurate imitation of the gulls. Is he trying to lure them in, perhaps? To what end? I can’t quite make out his game. He keeps it up the whole time, occasionally saying something in Arabic to his companion and chuckling, and then whistling his gull-call again. After a while, they move on, whistling. His friend must have the patience of a saint. You get all sorts in Brighton.

A few seconds later, a herring gull lands on the parapet. It’s not there for long, as a gang of girls in tracksuits race up the aisle towards the gloom of the arcade, screaming and swearing, sending the panicked bird into the air in their wake. Two scavengers in a truck trundle by in the opposite direction, trailing two heavy GLASS ONLY bins behind them. The planks tremble beneath my feet. I imagine, for a moment, the structure collapsing beneath its weight. In slow motion I see the bins rolling over backwards and a cascade of bottles plummeting into the sea below, some of them shattering on the struts of the pier before they hit the water. I have a pretty active imagination.

I move on up the pier, past the booming darkness of the arcade, which still seems to draw in a faithful clientele, despite the mobile lure of pocket entertainment. In fact, I’m actually pleasantly surprised by the absence of phones on the pier – for once, I’ve got mine out more than most as I take notes. Beyond the arcade, I reach a collection of outdoor game stands. Tin Can Alley with a bored-looking brunette in a red shirt waiting for custom. Dolphin Derby with an enthusiastic announcer who wouldn’t look out of place in a pinstripe waistcoat and boater a hundred years back. An Indian family points out across the water talking in a language that isn’t English. A couple walk past, hand in hand, one of them gamine with a grey-tinged ponytail over shaved sides and a nose ring, and her partner robust, black, ripped jeans and winged eyeliner, a rainbow lapel badge pinned to her sleeve. The air is thick with the pungent smells of Brighton: fish batter, candy floss and the distinctive damp tang of weed. The breeze coming in off the sea cancels out one of the three at a time, but not for long.

Behind the Tin Can Alley shack, a huddle of turnstones get some shut-eye. These often hyperactive creatures look out of place when static, and one wonders how they manage to get any rest at all with the thumping bass from the fairground rides at the end of the pier. It almost looks as though there’s a physical pecking order to the clan, and the ones at the bottom aren’t having much luck, hopping from strut to strut with remarkable dexterity. A passer-by sees what I’m looking at and stops to take a few photographs on her phone. The turnstones don’t seem to be fazed by me, or her, or any of this. After all, it’s fun all year on Brighton Pier. They’re probably used to it.

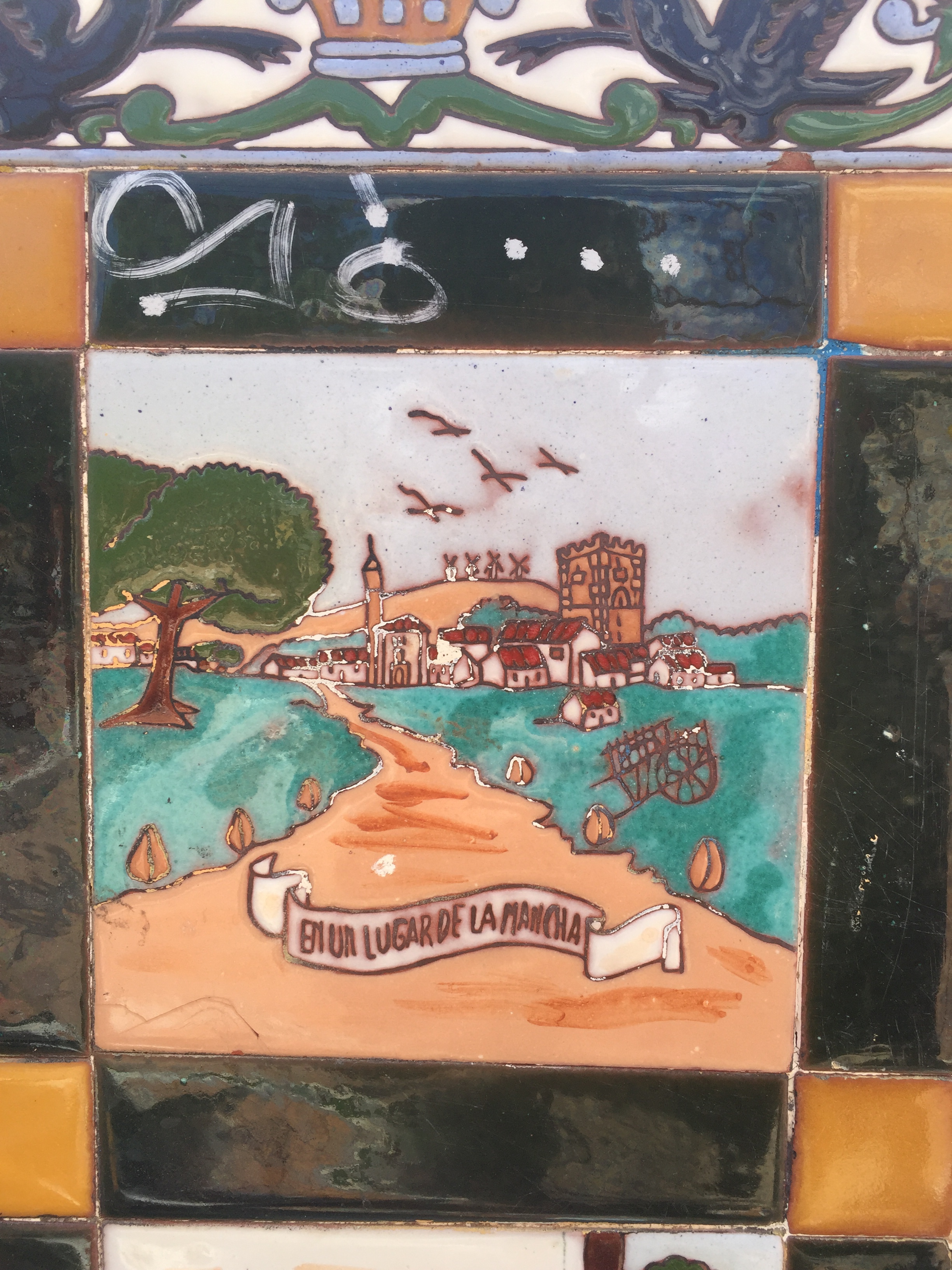

Nearer the fairground, an old gypsy-cart sits awkwardly beside the parapet, offering Tarot readings for a modest sum. Career, love, happiness and luck mingle strangely with Nestle, Astra Zeneca and Cornhill Insurance plc. I remember finding an abandoned gypsy-cart in the woods once when I was a child, its richly-painted woodwork fighting a losing battle with the forest’s silent army of moss, lichen and brambles. The gitanos in Tierra de Barros had no such fancies, eking out a living from beat-up cars and shabby tents. There is an old song of theirs I have consigned in part to memory, telling of their love for the Guadiana River, that came to mind:

The region of Chal was our dear native soil,

Gypsy ballad, translated by George Borrow (The Zincali, 1841)

Where in fullness of pleasure we lived without toil,

Til dispersed through all lands ’twas our fortune to be,

Our steeds, Guadiana, must now drink of thee.

I doubt the gitanos camped outside Villafranca de los Barros would know the song. It comes from an older world, much like the incongruous cart parked at the end of Palace Pier.

The fairground plies a busy trade for a chill-if-sunny Sunday in March. I feel like I’m walking through a childhood I haven’t known in twenty years, not since the distant summers in Dymchurch. Tea cups, log flumes and merry-go-rounds. A helter-skelter – see the Isle of Wight on a clear day! – painted up like a stick of Brighton Rock (or maybe the sticks are painted after the fashion of the fair). The static gilded horses on the merry-go-round look no less terrifying than they did when I was a boy. The ghost train reels in customers one at a time, lethargic, a chameleon in the cold. A father explains the “this high to ride” sign to his son, who is just a little too short for any of the attractions. I get the impression I’m snooping a little too much and wander away from the noise.

There’s a quiet spot behind one of the rides, looking out towards the mouldering wreck of the old pier. Seen from its sister with the city behind it, the Western Pier looks small and unimpressive. From the shore it looks a little more mysterious, where its mangled skeleton claws at the horizon like the blackened bones of a giant, mechanical whale, picked clean by the cormorants that sit on its ancient struts. In their oil-black funeral garb, they might as well be an extension of the wreckage. Brighton’s gargoyles.

Something bobs in the water closer to the Palace Pier, and without looking through any lens it looks too misshapen to be a buoy. It turns for a moment revealing long whiskers and those baleful black eyes, before sinking beneath the waves. I’ve been scanning the water all morning for that sight, and now I’ve found one, I can’t let the moment pass me by. I count the seconds. One, two, three…

Seals are such mesmerising creatures to watch. It could be their friendly faces, the way they seem genuinely curious about the world above the waves. For me, it’s all about their eyes. There are few creatures out there with eyes like a seal’s: enormous, black orbs that seem to see forever. You only see the whites of a seal’s eye when they’re really close, otherwise you might as well be looking into the dull glaze of a shard of volcanic glass. I used to watch them bobbing about in the waves from the white cliffs when I was a teenager, and once or twice I was lucky enough to see them closer still, lounging about on the mudflats of the Stour Estuary and snorting their indignation at the noisy ferry-boat off the Farne Islands.

Those were greys: hulking, dog-like beasts of considerable size, especially the bulls who came charging after the boat. It’s not hard to see why so many languages label the creatures sea-dogs, or sea-calfs, or even sea-cats. But unless you’re in the water with them, all you see is the inquisitive face, bobbing above the surface. The seal comes into its own beneath the waves. I should love to see one in its murky underwater kingdom one day.

Some creatures command the eye. The ghostly silence of the male hen harrier, or the aerial mastery of the kite. The sunken eyes of the fox and the stern gaze of the stag. I once sat in my bedroom poring over bird guides of Spain and the Mediterranean, bemoaning how drab our world was by comparison. With age comes understanding, I suppose. If the seal hadn’t drifted further and further out to sea, I could have watched for hours.

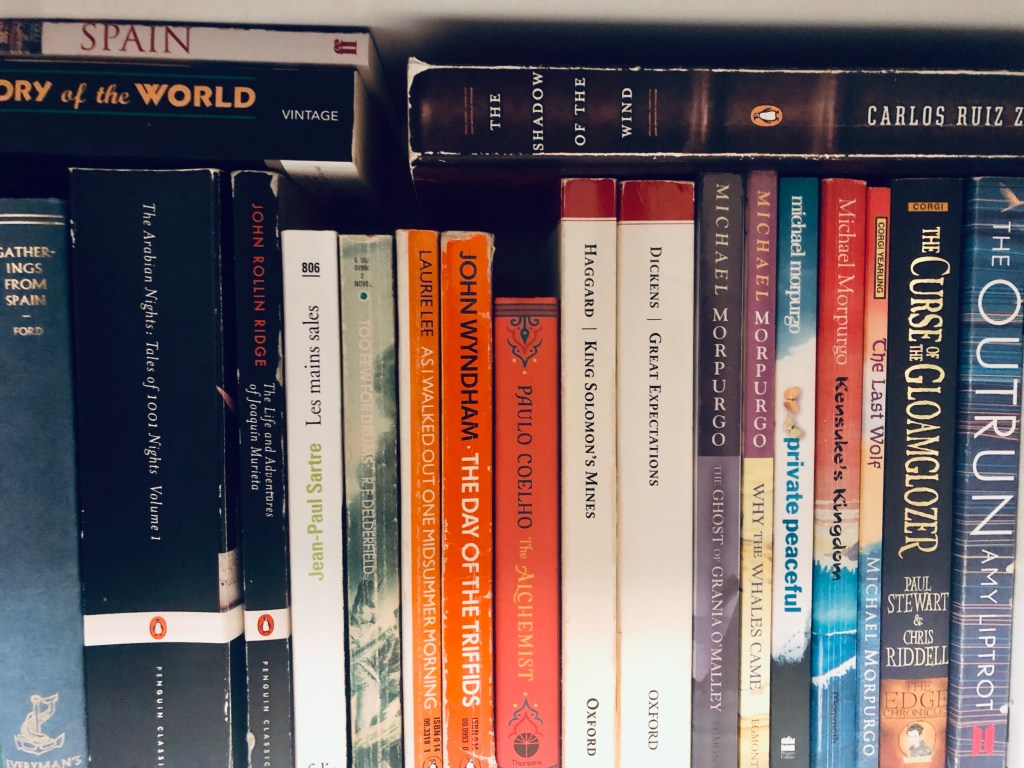

I spent most of my teenage years growing up on the pebbled shores of this same stretch of ocean. The salt breeze and yellow-grey skies of the Channel are written into my skin like age-lines. I should make a point of coming down to the coast more often in future, if not to blast the cobwebs of work aside with a healthy salt spray, then to find the writing material I’m always searching for. If I can find my way to a quieter spot than Brighton, I might even be able to sidestep the bookshops that always draw me in. Fortunately, I’ve been such a loyal customer to Waterstones over the last couple of months that I was able to walk away from today’s haul for a steal of a price. Just don’t ask how many books I bought – or how big the discount was. It’s all for a good cause. I’ll keep telling myself that. BB x