Wandering the streets of Paris, it’s easy to understand why the city was surrendered to the Germans without a fight in the summer of 1940. I have been lucky enough to see a number of beautiful cities all around the world, but there is something truly exceptional about the French capital – calm, curated, unspoiled. As the official line went in that dreadful summer, as Britain stood alone on the edge of a darkening Europe, “no valuable strategic result justified the sacrifice of Paris”. The West is full of cities scarred by the ravages of war, and while it may have earned them an unfair reputation for cowardice in popular culture, you really have to admire the gall of the French for putting their beloved city above their freedom, the first and foremost of their three sacred values. It gleams to this day.

A personal mission took me to Versailles, on the outskirts of Paris. My Metro pass was only for Zones 1-3, which was one stop shy of the Château itself, but I was very grateful for the break. The half-hour walk to the famous 18th century palace takes you through the tranquil suburbs of verdant Viroflay, and with the mottled darkness of the Meudon Forest rising up and over the hill behind you, Paris seems a lot more than half an hour away.

I came here in search of a shot glass, of all things, but I found something far more arresting: an exhibition of equestrian paintings of immeasurable beauty. So I’ll take you on a little tour of the inside of my head as I stood there in awe.

The first one to catch my eye was an enormous tableau by the 19th century artist Evariste-Vital Luminais, known as the painter of the Gauls. Titled La fuite de Gradlon, it tells the story of the escape of King Gradlon from the legendary city of Ys, the Breton counterpart to Atlantis. The tale tells that Ys was destroyed when the king’s wayward daughter, Dahut, opened the dikes that protected the city from the sea, ostensibly to allow her lover in to see her. Fleeing the destruction across the sinking floodplain, Gradlon’s friend and advisor, Saint Gwénnolé, implored him to cast off the demon he brought out of Ys, or risk losing his own life in the endeavour. Dahut was thrown into the merciless sea, and Gradlon and Gwénnolé escaped with their lives. I guess that makes it the oldest account of the “begone thot” meme.

I have always been captivated by stories of Atlantis. Dig deep enough and you’ll find stories of sunken cities all over Europe: Tartessos, Akra, Saeftinghe and Rungholt. Tolkien’s Numenor might even be considered a fanciful addition to that list. I should give this Ys legend a closer look.

No prizes for guessing the subject of this one: it’s the naked ride of Lady Godiva by the English pre-Raphaelite painter John Collier. Most depictions of this legend have her riding side-saddle, an enduring medieval custom that preserved a woman’s modesty by keeping her knees together while reducing the risk of an accidental tear of the hymen (the age-old proof of virginity). Collier has her riding astride, all the stronger for her position, focusing on her dauntless courage in the face of her husband’s oppression.

It isn’t easy to remember one’s sexual awakening, or when and where it began. I’ve seen various authors ascribe theirs to a range of sources, from the older siblings of friends and schoolteachers to National Geographic magazines and Uma Thurman’s role in Pulp Fiction. I didn’t exactly gobble up popular culture in the Nineties and Noughties with the same fervour as my classmates, so I think mine started with an illustration of Lady Godiva in a children’s book of folktales and legends – if not with the Little Mermaid (setting in motion a lifelong fascination with red hair that has proved impossible to shake).

You couldn’t have an equestrian exhibition without at least one painting of the famous Valkyries of Norse legend, shield-maidens and psychopomps that herd the souls of the slain to Valhalla, the Hall of the Dead. It’s a dark and moody piece, but I would have given a great deal to see Peter Arbo’s more famous painting, Åsgårdsreien, which depicts Odin’s “Wild Hunt”, a spectral apparition said to appear on stormy nights as a herald of woe and disaster for the beholder. I’ve had a thing for that folktale since I found its equivalent in Cataluña, centred on the doomed Compte Arnau who rides again at night with skin afire, pursued by his hungry hounds. There’s even a country song by Stan Jones about the famous “Ghost Riders in the Sky” that Johnny Cash went on to cover, which has the Valkyries of old trade in their helmets for stetsons.

I do love it when a myth goes global.

One painting in particular caught my eye (and not just because the leading lady has red hair!): Crepúsculo by the Spanish painter Ulpiano Checa y Sanz. Even without the aid of the title, you know straight away what you’re looking at by the colours alone: the halcyon flash of twilight, as the last rays of the setting sun scatter across the darkening world in a brilliant array of colours. Am I glad that the painting that really took my breath away was crafted by a Spaniard? You bet. The landscape below reminds of the opening crawl of the Charlton Heston El Cid film, and in its strange and featureless way, it is so very Spanish. Foreign painters of Spanish scenes often play up to the Romantic stereotype of dusky maidens with hooded eyes lounging on street corners with flowers in their hair, so it’s nice to see a native sharing my weakness for a change.

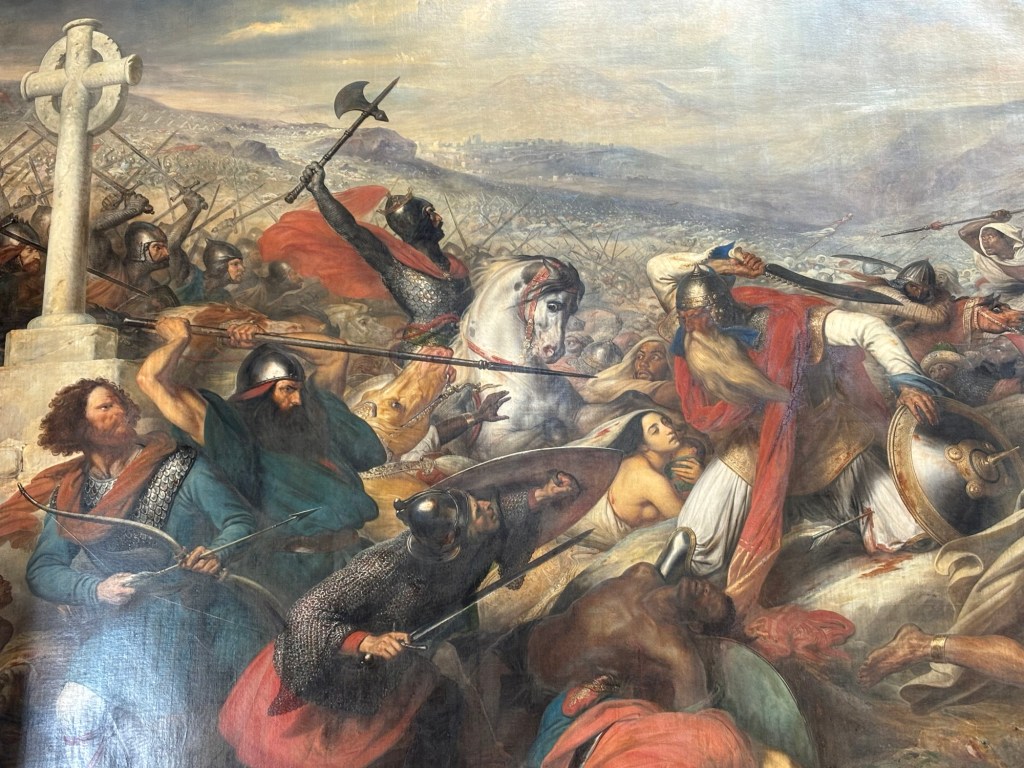

Finally, a painting I really didn’t expect to see, but one that must have been at Versailles for some time, as it was not in the equestrian exhibition but in the palace’s Galérie des Batailles. As patriotic paintings go, it’s got to be up there with La Liberté guidant le peuple by Delacroix (though perhaps not as widely known). This is Charles de Steuben’s Bataille de Poitiers en octobre 732, and it tells the story of the decisive battle between the Frankish forces under Charles Martel, “the Hammer”, and the invading Umayyad army Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi. I must have seen this painting a thousand times for it is tied up with the history of Spain, and of Europe itself: had the Umayyads not been stopped so decisively, they might well have gone on to conquer the rest of Europe. It’s one of those real watershed moments that comes around but rarely in history, and I was amazed to see the real thing – which is, like the armies it portrays, vast.

Not a good time to be a horse, or a European for that matter, but what a find!

Well, that’s quite enough painting perambulations for one post. I’ve just arrived in the pirate city of Saint-Malo where the sun is shining and the water is crystal clear. I think I’ll go for a dip while the weather holds! BB x