Tomorrow is the first day of a new life. After a long summer of alternating adventures, up-and-down driving lessons and watching the clock, it’s back to school for this bleeding heart. I’m determined to make a success of it. Once again, I find myself thinking back to my first teaching post in Uganda, nearly twelve years ago – where it all began. Did I know it then? I must have had an inkling – that was partly why I went, to see if teaching was for me – but I suspect I was blinded by the lure of seeing Africa with my own eyes. My lanyard is hanging from the door, my notebook is on my bedside table and the pen pot on my desk – a gift in the shape of a Dia de los Muertos mug – is stuffed with fully-loaded board markers. It’s nearly time to get started. But for now, let’s dive back into the realm of memories; to a remote farmstead on the banks of the White Nile…

9th October 2012

Ugandan Independence Day (50th Anniversary)

One month into our stay in Boroboro in northern Uganda, Luke Ojungu came trundling into the driveway of the Bishop’s compound in his enormous four-by-four. With Uganda on the brink of celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of its independence from Britain, we had an unexpected holiday on our hands and the former headmaster had offered to take us to stay at his farm in the Apac region to the southwest. The bishop said a prayer to bless our journey and send us on our way with God’s protection, though Luke’s impressive 6’5″ stature might well have been all the protection we needed. His plan? To show us a corner of Uganda we might not see otherwise, and to put us to work herding his cattle.

No visitor to Uganda who makes it out of the capital can possibly miss the famous Ankole cattle. For one thing, they’re everywhere, and for another, their enormous horns make them easy to spot over a great distance. I wonder if that was an intentional bit of genetic wizardry on the part of the cattlemen, so that they could keep stock of their herds from far away?

Luke had several hundred longhorn cattle spread across his lands south of the river, along with a large number of goats and chickens back on the home farm, which by Ugandan standards (or any standards, for that matter) made him a rather wealthy landowner. He was very keen to point out Matthew, the hornless bull he had named after the headmaster of our school back in England. It was hard to tell whether it was an affectionate gesture or somewhat tongue-in-cheek, choosing the one longhorn bull without horns for such an honour, but we had a laugh all the same. A running in-joke was born and Matthew “the most indie cow in the world” and his distaste for anything mainstream kept the four of us amused all weekend.

We arrived in time to help with administering the inoculations, which had already taken a couple of days, what with the herds spread out across the forested hills. Maddie, the team scientist, took the lead on this one, seeing a chance to do a little fieldwork ahead of the Biology degree ahead of her. Several years ahead of the rest of us in maturity and wisdom, if not in age, she was always out in front and seizing any and all opportunities that came floating our way, whether we joined her or not. It was Maddie’s idea to go to Uganda in person to snag a better deal on the national park permits. It was Maddie’s idea to spend all night dancing with locals down the road from our tumbledown hotel in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. I should have followed her lead more often.

Mind you, it was also Maddie’s idea to ride along with the staff to a remote village in the north to the funeral of a colleague we’d never met, even though the service was conducted entirely in Lango (of which we understood perhaps four words between the four of us) and the return journey had me sandwiched between quite possibly the two largest women in Uganda.

With jabs administered, Luke left us in the care of two of his cattlemen, Alphonse and Gideon (I definitely misheard Gideon as Geryon the first time around, since that’s what I wrote in my journal, though that would have been a very fitting name for a cattle herder!). Out in the bush, I got my wish: to explore a proper African wilderness. True, it was grazed by Luke’s hundred-strong herd of cattle, but there were wild things everywhere: drongos, hornbills, cuckoos, parrots and forest kingfishers. Overhead, the awkward silhouette of a pair of bateleurs kept us company across the open marches. In the course of a single cattle drive I counted at least forty species I’d never seen before, jotting down details of what I’d seen and sketching while the memory was fresh.

In short, I’d make a decent Darwin, but a useless cowherd.

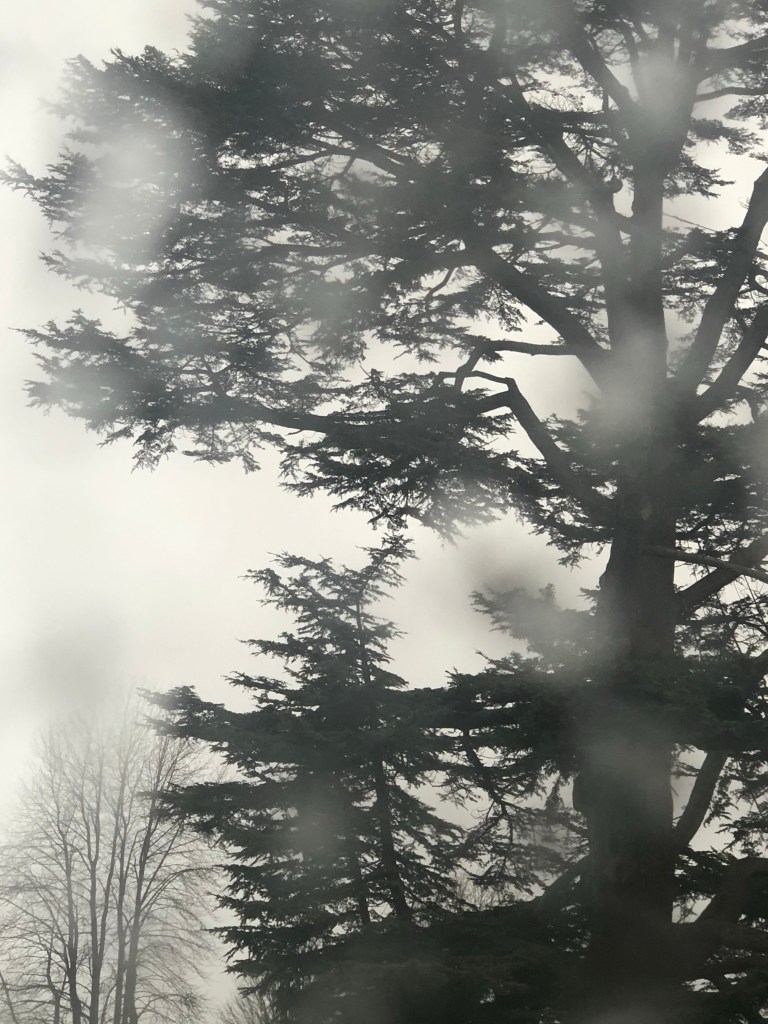

The drive took us deep into the forest, which swallowed up the herd quite capably. The going was a little hard, with thorny acacia branches poking in all directions, and we got to wondering whether we were being watched by other, more sinister residents of the forest as we cut a path through the trees: our encounter with a troop of baboons at the crossing at Karuma the day before had left me with a deep-seated awe (and justified terror) of the things, and I couldn’t shake the idea that they might be hiding in the trees, watching us from evil, sunken eyes.

I needn’t have bothered: the great herd of longhorns drove most of the forest creatures before it like a scourge. But it’s funny what gets into your head.

What was waiting for us, however, was a tropical storm. We had reached the heart of the forest, where the bush was at its thickest, when Alphonse brought us to a stop at the sound of a heavy drumroll from the north. Gideon went on ahead to divert the herd, but we had gone no further than a hundred metres when the heavens opened. It did not happen gradually, as rainstorms do in the British Isles, but in an instant: one minute the sky was grey with promise, the next it was sheet-white and bucketing it down. It was as though somebody had turned on an almighty showerhead, the way it just came down all of a sudden, and it went on for the best part of an hour. At Alphonse’s suggestion we sheltered beneath the scant cover of the trees, holding the herd at a standstill while we waited for the worst of it to pass. The waterproof hiking boots which had endured similar conditions in the Lake District were waterlogged within minutes, and we were all of us soaked to the skin – it was hard to imagine that only moments before it had been a balmy thirty degrees and we had been bemoaning having run out of sun lotion. I don’t think I have ever been so utterly drenched. If I remember correctly, I was quite miserable. We all were.

Luke came to the rescue around midday, picking us up from the side of the road when we finally broke free of the forest and saw the Nile, our intended destination, winding across the valley ahead. Regardless of the conditions, it would still have been another couple of hours’ march to the river, and Luke was quite anxious that we would not catch our death of cold on his watch, so we were whisked back to the farm for a warm cup of tea and fresh clothes. Alphonse and Gideon bade us farewell and pushed on toward the river, even as the clouds threatened a second deluge with flash and thunder.

We conceded defeat before these incredibly hardy cattlemen and their herd, and returned to teaching the following week with a renewed sense of purpose: we had a lot more to offer in passing on what we had learned than in wandering blindly through the bush in the wake of men who had been herding cattle since they were children.

I said I was miserable – which, according to my diary, is a fact – but like most things that get me down, I’d do it all again in a heartbeat, if only to see the rain come down as ferociously as it did that day, and to feel that shudder in my heart when the first drumroll of the rainy season came thundering in. Matthew wouldn’t have thought all that much of it. After all, there’s all manner of cliches when one gets to talking of a thunderstorm, and Matthew is far too indie for any of that nonsense. BB x