Masks are becoming a much less common sight around town these days. Most of the signs in shops still carry the warning to wear a face covering or face a penalty, but only the employees appear to follow the rules nowadays. John Q. Public seems to have taken Boris at his word and thrown caution the wind in favour of a return to the way things were. The lurid rojigualda of my own face mask is more notable for its presence than for its colour scheme.

Though perhaps less so today, when red is absolutely everywhere, in the name of love, romantic, commercial or otherwise.

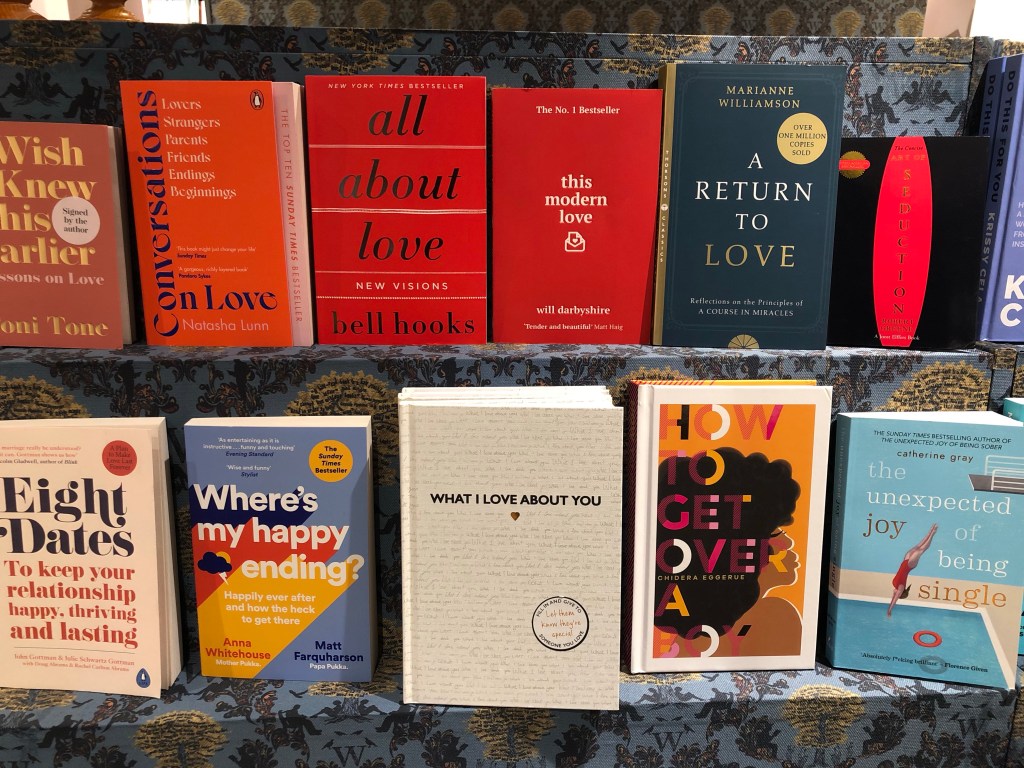

There’s been a pretty serious push for Valentine’s Day this year. Did you notice? I suppose it’s because we’ve had two years of two-metre rules and vaccination anxiety which has thrown the world’s dating community into total disarray. Still – it looks as though all the usual suspects are making up for lost time. Couples wandering about, hand in hand, head on shoulder. Trendy-looking young men scribbling hasty cards in cafes. Groups of girls carrying bouquets and single roses around every corner. Supplying them all, flowers stalls plied a roaring trade in every train station, booksellers put all their romcom collections in the window and Lush had its usual ‘leave a message’ montage daubed across its front.

I’ve never been one to hate on Valentine’s Day. Somehow all those years at an all-boys grammar school didn’t manage to quash the romantic in me. Sure, it’s got a commercial side these days, but then, what doesn’t? It may seem a little strange to celebrate the death of a third-century Roman saint by giving and eating (or just eating) a confectionery staple that the Mayans used to snack on, but is it really any weirder than Santa Claus’ transformation over the centuries from Turk to Coca Cola-chugging Nord?

I was raised on Disney movies, so of course I’m going to fight love’s corner. The same mega corporation that imbued us all with a considerable mistrust of employers (seriously, how many Disney villains use contracts or bargains?) has hammered home the message that true love conquers all since 1959. And though Sleeping Beauty gets its fair share of scrutiny these days, there’s a no less powerful dialogue from The Sword in the Stone that cuts (ha) right to it:

Merlin: “You know lad, that love business is a powerful thing.”

Arthur: “Greater than gravity?”

Merlin: “Well, yes, boy, in its way… yes, I’d say it’s the greatest force on earth.”

The Sword in the Stone (1963)

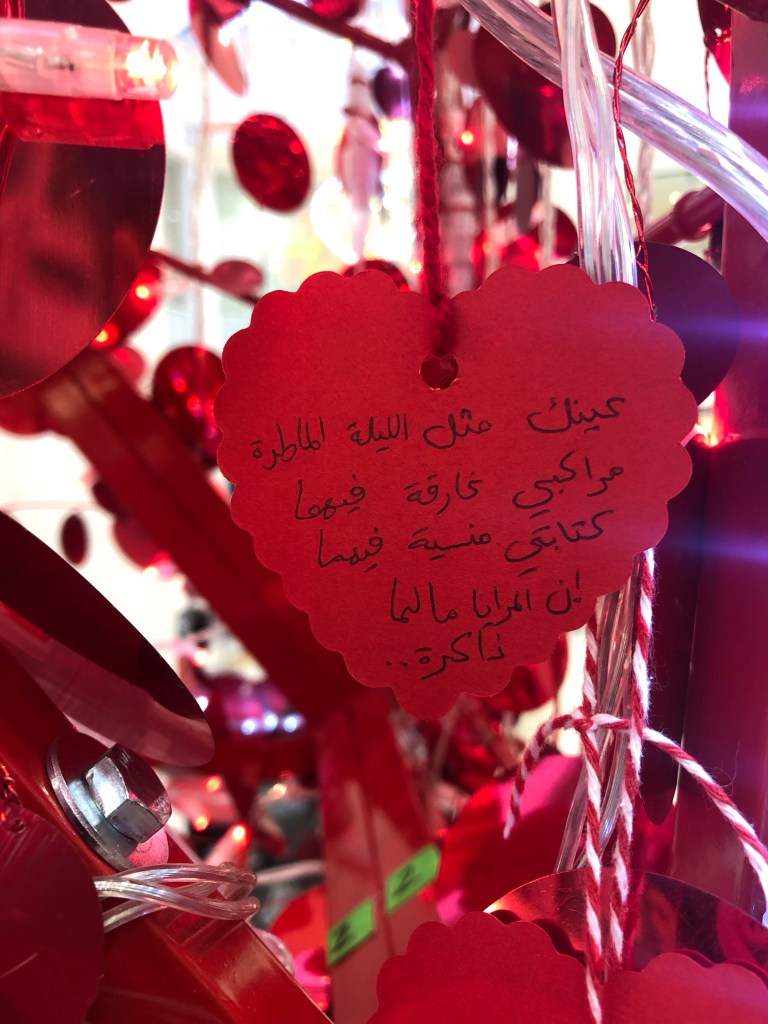

Lincoln’s town mall had an oversized display up which was drawing a small but steady stream of contributors, so I had a look. Folk had scribbled messages on little red hearts and strung them up from the display for all to see. Lots of “luv u Dave!! xoxo” type notelets, but a fair scattering of wise words threaded in: “Happiness will come to everyone at the right time”, “Don’t look for love it will find you”… “Snap me @.”

When I woke up this morning with this post in mind, I meant to read some good old love poetry and reel off that. I could only find a few that were to my liking in my poetry collection, namely a couple of Shakespeare sonnets (18 and 116) and Yeats’ He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven. It wasn’t until I reached the garish display in Lincoln’s mall that I suddenly remembered one of the greatest poets to ever put love into verse: the Syrian wordsmith, Nizar Qabbani.

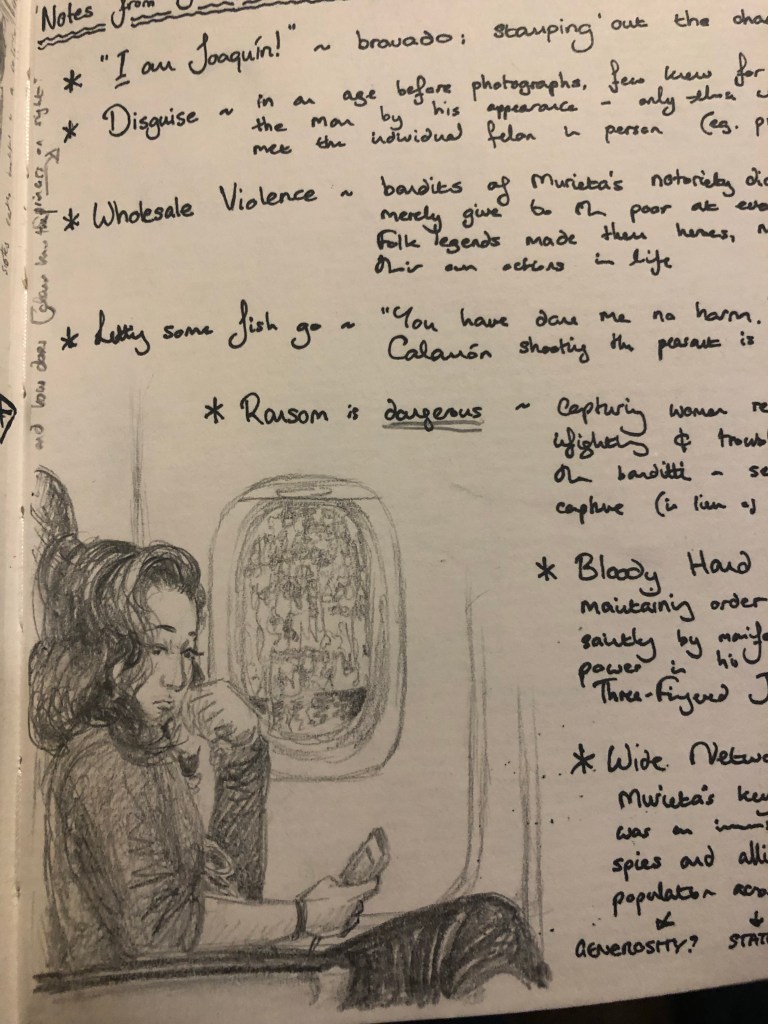

I’ve been a devotee of Qabbani’s work since I was introduced to him in my second year at university. There’s not a single one of his poems that I don’t adore. Even in translation his words hold their magic. His poems find their way into my journals at least once per book, and I couldn’t resist an opportunity to transcribe one of his verses here, for want of anything better to write. I’ll translate below:

Your eyes are like a rainy night

My boats sink in them

My writing disappears in their reflection

Mirrors have no memory…

Nizar Qabbani

Three local girls were busy penning their thoughts as I strung up my contribution and set off to catch my train. When I glanced back at the door, they’d all gathered to see what I’d written. I hope they find the words as powerful as I do.

As is so often the way after such highfalutin flights of fancy, I was brought back to reality with a crash when not even a minute later I was stopped by a drunk almost as soon as I’d stepped out into the street. Between slurred speech and staggered gait he managed to convey that he had ‘no credit’, the taxi people ‘weren’t talking to him’ and that he needed to get to ‘Cherwillingum’, though he couldn’t say where exactly. After we’d established that his destination was Cherry Willingham (which, apparently, is how the locals say it – I maintain that British place names make English the most unhelpful language on the planet), I called him a taxi and wished him good luck, hoping that the three-hour wait would find him in a more sober state. Fingers crossed for you, buddy!

The sun sets on another Valentine’s Day. Eros and Mammon join hands once a day every year, and frankly, I say let ’em have their fling. It’s very easy to roll your eyes at the consumerism and mawkish PDA everywhere, but I can’t help feeling there’s nothing wrong with one day out of 365 devoted to romantic love. That leaves at least 364 others to be a cold-hearted cynic, if you’re that way inclined. BB x