Albergue Seminario Menor, Santiago de Compostela. 18.11.

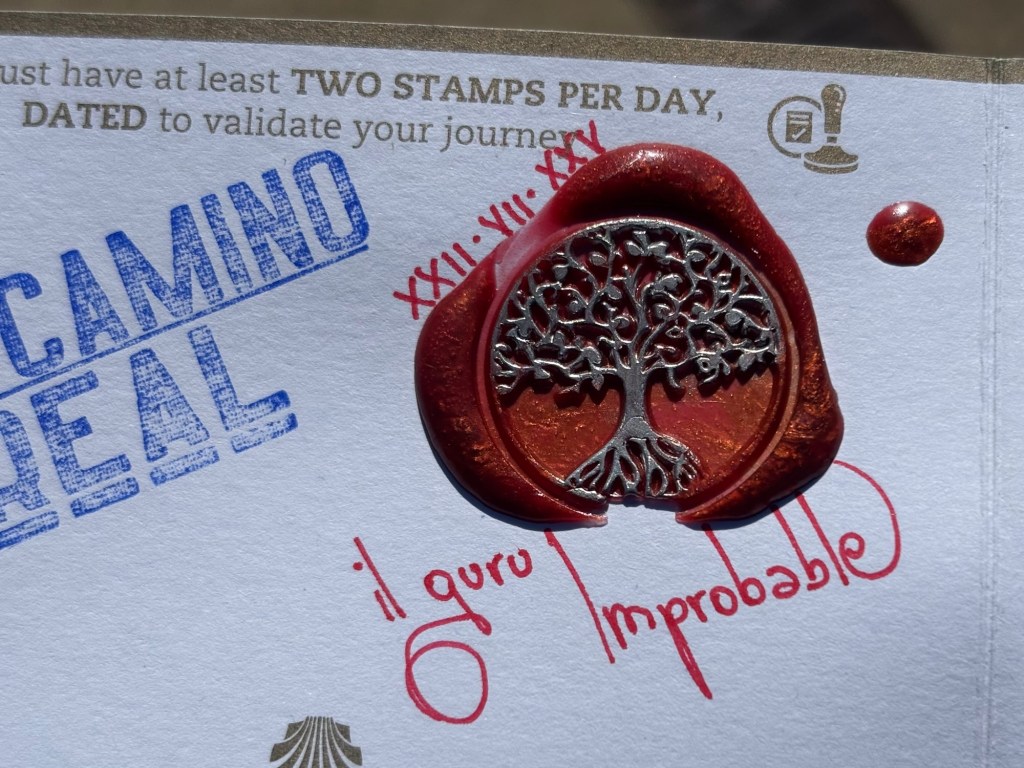

Two years ago, when I walked into Santiago’s Praza do Obradoiro under a cool white cloud, I could not shake the feeling that I had not quite earned the triumph that the end of the Camino usually entails. I had walked in alone, in the early hours of the morning, after setting out from Burgos some twenty-one days prior. My credencial showed that I had walked all the way, but not all at once: my circuitous route had taken me four years, starting in the summer of 2019 and continuing in the spring and summer of 2023, after COVID and a number of other factors prevented me from walking further.

Not this time. Today felt like the finish you read about in books and in the films. Today, after walking over a thousand kilometres across France and Spain, to be welcomed like a hero by old friends in front of a crowd of thousands before a cathedral bathed in light… I was on the verge of tears this time.

Ribadiso was silent when I left at around a quarter to five this morning – the earliest I have set out along the entire trek. A few cows had wandered down to the river for a drink by the reflected light of a few lamps along the bridge, but I could hardly make out more than their silhouettes in the gloom. My phone did a much better job than my eyes could do.

Darkness shrouded my steps until well after seven o’clock, so the first two and a half hours of my walk were made in the long shadows of night. As usual, I avoided using my phone’s torch as much as possible, navigating by starlight and the shadows of the trees against the sky, turning it on only to check I was not in any danger of leaving the trail. I passed a few pilgrims on the road who turned their glaring flashlights on me as I motored past, no doubt perplexed as to why I had decided not to light up the way in front of me.

I picked up considerable speed whenever I saw the dim moving light of a headtorch on the road ahead. I have not been a huge fan of headlamps and torches since two were trained on me like searchlights at two o’clock in the morning on a beach in Almería, during my mad trek across Spain at the age of eighteen. The fright that experience gave me has never really gone away, which may go some way to explaining my general disdain for the invasive, almost threatening white light of a handtorch. But there’s also my natural stubbornness, which I suspect has much more to do with it. You don’t really need a torch to navigate by night… not when your eyes grow accustomed to the gloom. So why bother?

I considered stopping for breakfast at a number of cafés once they started to open their doors after 7am, but every time I neared one, it looked packed to the gills, so I moved on. If I’d known that this would be the case all the way to Santiago and that I would not stop again until I reached the holy city, I might have shrugged off my pride and popped in for a tostada. But I didn’t, and when I accidentally took the forest route bypassing O Pedrouzo altogether – the usual staging post before the final push to Santiago – I decided to push on to the end on the power of a Bolycao and the last of my Nakd blueberry bars. It wasn’t much of a breakfast for a forty-three kilometre hike, I’ll admit, but it did the job.

The road got quieter before O Pedrouzo after I had overtaken all of those pilgrims who had set out from Arzúa, only to ramp up again as I hit the back of the O Pedrouzo brigade. I met a few new characters as well as the first of a few old faces from the Camino Francés: Don Decibel, a raucous Spanish soldier whose phone call to his friends ten kilometres back hardly required the use of a phone at all (though I’m not sure I’d count the repeated phrases “oyé maricones” and “viva España putamadres” as a conversation); the Shadow, a French pilgrim who seemed to catch up to me constantly despite my attempts to race on ahead; Tim & Jackie, an Australian couple who fell behind us at Carrión de los Conded when Tim’s legs started to cause him trouble; and Edoardo, the charismatic Don Juan, who had slowed down to walk with a large group of Italian pilgrims.

And then there were the school and university groups. Hundreds of them. Well over a thousand, if I’d bothered to count them all. The ticker in the Pilgrim Office in Santiago showed that 847 had already made it to the city before I arrived at around twelve o’clock, so that number is not as much of a hyperbole as you might think.

The post-Sarria rush is real. It wasn’t quite as obvious two years ago as it is now, in the middle of August, when the crush is at its highest. I’d wager that I’d have seen even more if I’d left even a little later. They were all in very high spirits and many of them were draped in the colourful flags of their home regions: Andalucía, Valencia and Asturias were the most obvious. I looked for the black bars of the Extremaduran flag, but I didn’t see one.

I wondered, if I’d carried a flag, which one I would have the right to bear. Not Andalucía, surely, as I only lived there for a little under a year as a child (though it has forever marked my accent and identity), and not Extremadura either, since I have no familial connection to that earthly paradise whatsoever. La Mancha, perhaps, as that is where my cousins reside – but when my great-grandmother was born, that part of La Mancha was part of Murcia. My grandfather and his father, on the other hand, were from the Valencian province of Alicante.

In short, I have no claim to any of the regional flags. So I would have settled for the rojigualda instead.

I couldn’t find the famous pilgrim statues on Monte do Gozo – I wonder if they’ve been moved to a different location? Their pedestal was where Google Maps said it would be, but I could not find them. I did, however, see my destination for the first time, and that was motivation enough to proceed: the twin turrets of Santiago’s cathedral, between the gleaming white houses and the towering eucalyptus trees.

When I left Ribadiso this morning, Google Maps thought it would take me around nine hours to reach Santiago. It took me seven. I had some powerfully uptempo music to get me through the last ten kilometres, up to and including:

- Rhythm is Gonna Get You – Gloria Estefan

- Higher Ground – Stevie Wonder

- Voodoo Child – Rogue Traders

- El Cid March – Miklos Rozsa

- It’s a Big Daddy Thing – Big Daddy Kane

- Qué Pasa Contigo – Alex Gaudino

- Walk Right Now – The Jacksons

- Deliver Us – The Prince of Egypt

The last one was the killer. I get emotional listening to that track at the best of times, but the timing was absolutely perfect, reaching the triumphant crescendo finale just as I reached the back of the square and turned to face the cathedral. There really were tears in my eyes this time.

Let’s face the facts. I walked a bloody long way.

I had hardly arrived in the main square when I was jumped by three old friends: Juha the Finn, Max the Austrian and David the American. To be honest, I was not expecting to run into any of the old guard at all: my side quest over the San Salvador and along the Primitivo put me almost a week out of sync with the crew I had walked with, and even three double days wouldn’t have been enough to catch up to them all.

However, with the exception of Chip (who left for home several days ago) and Audrey and Talia (who I missed by a matter of hours), everyone else was here, including Alonso and Gust, the last remaining members of our little band of seven. I could not have hoped for a better welcome wagon.

Alonso, Gust and I are all at the Seminario – along with a good number of familiar faces – and we had a decent lunch (if a bit pricey for what it was) and a phenomenal Gujarati supper at Camino Curry, a brave new enterprise by a family from Birmingham that was both the most delicious and the friendliest meal I have had on the entire Camino. Given that the fellows had been advertising on my Facebook posts, I’d say they earned my custom.

We said farewell to Max and Juha for the last time on this Camino and returned to the albergue for a couple of rounds of Go Fish (instead of watching the 10pm screening of the Superman movie at the local cinema and risking the nine minute dash back to the seminario before lock-up). I’m normally averse to card games but I had a great time. It reminded me of those dark internet-free nights in Uganda long ago, with Teddy and Maddy and Mina. That feels like a lifetime ago.

Well… tomorrow is another day. No more 5am starts. That’s something to look forward to! BB x