Somewhere in my room there’s a programme from a school play I was in back in my prep school years. A few of the lead roles were interviewed about their respective parts, and the boy playing Cardinal Richelieu said he “liked playing the baddie because it is more of a challenge.” My reaction to that line has changed very little over the last twenty-odd years.

Bull. Shit.

If twenty years of writing stories have taught me anything, writing villainy is easy – sometimes, alarmingly easy. Ambition, greed, selfishness and ego are everywhere. Depending on the orientation of your moral compass, you might even be inclined to disregard some of these behaviours out of hand as simple human nature. If you want a challenge, try writing or playing a hero. Finding convincing dialogue and/or motivations for a hero is hard because heroes require hard work: they are what we can become if we can find the strength and the courage to rise above our own desires. Selfishness, the root of villainy, however, is in us all by default. It doesn’t take much to make a villain, just – what did Heath Ledger’s Joker say again? – “a little push”.

What’s the first image that comes into your head when you think of a villain? I imagine it’s rather different to the image in my head. If I were a betting man, I’d wager it’s probably not the moustache-twirling Dick Dastardly-type, which went out of fashion a long time ago. The movie-going public seems to have lost its taste for gleefully evil baddies (so much for Palpatine!) in favour of the tormented anti-hero with quasi-legitimate motivations (a la Thanos). Avatars of utter darkness are on the out, and they’re taking their more rational minions with them. In some cases, this has led to the near-total disappearance of the bad guy altogether (see Inside Out and Moana, or even Encanto).

As a writer, this saddens me, for much the same reasons as the destruction of statues bothered me a few years back. Doing away with the villains of our world is like smashing up a mirror; just because you can’t see them anymore, it doesn’t mean to say they’ve gone altogether. We need to be reminded of the depths of our depravity from time to time. Every villain is a warning in his or her own way of the capacity for darkness in all of our hearts, and from them we learn to avoid their mistakes.

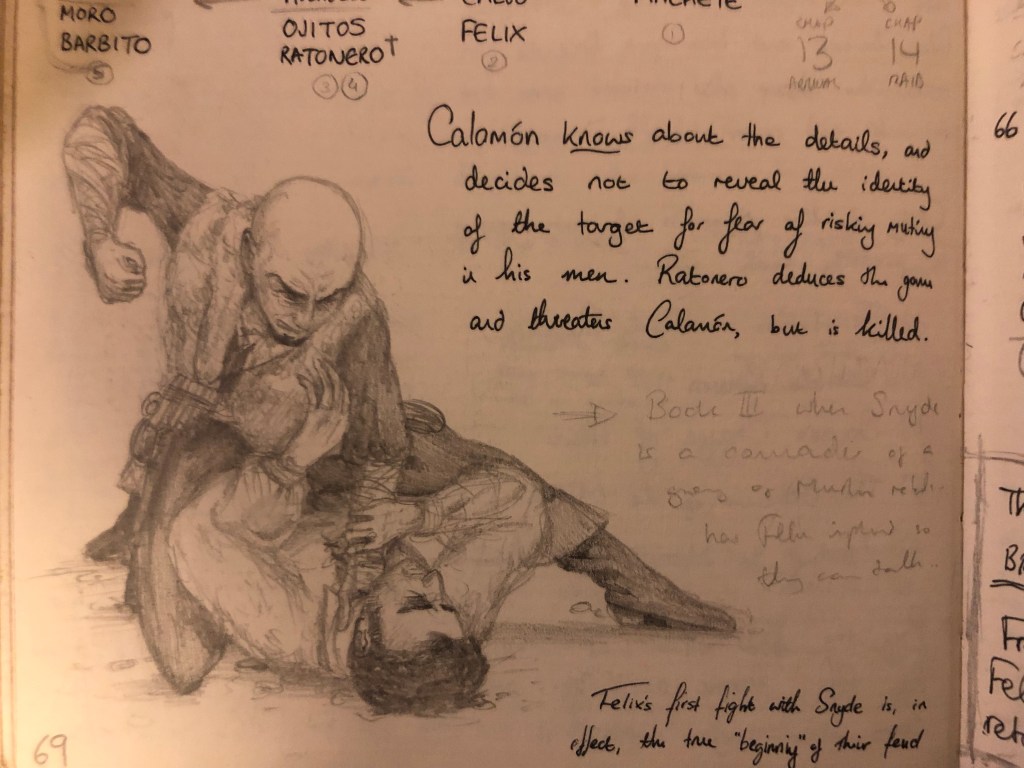

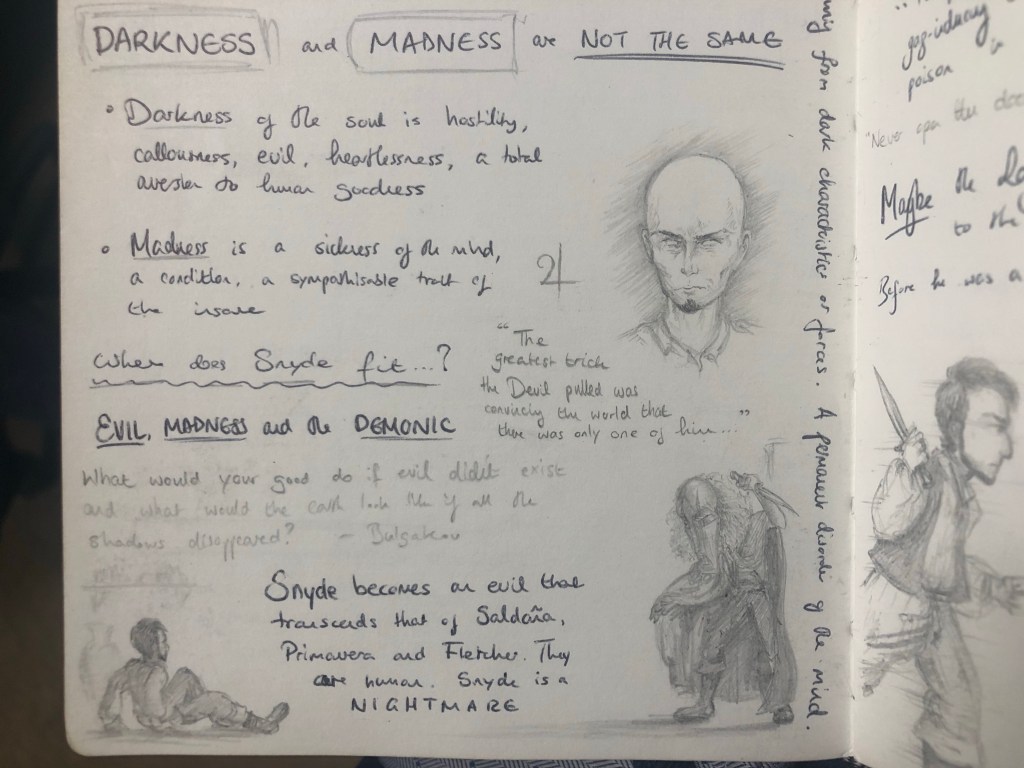

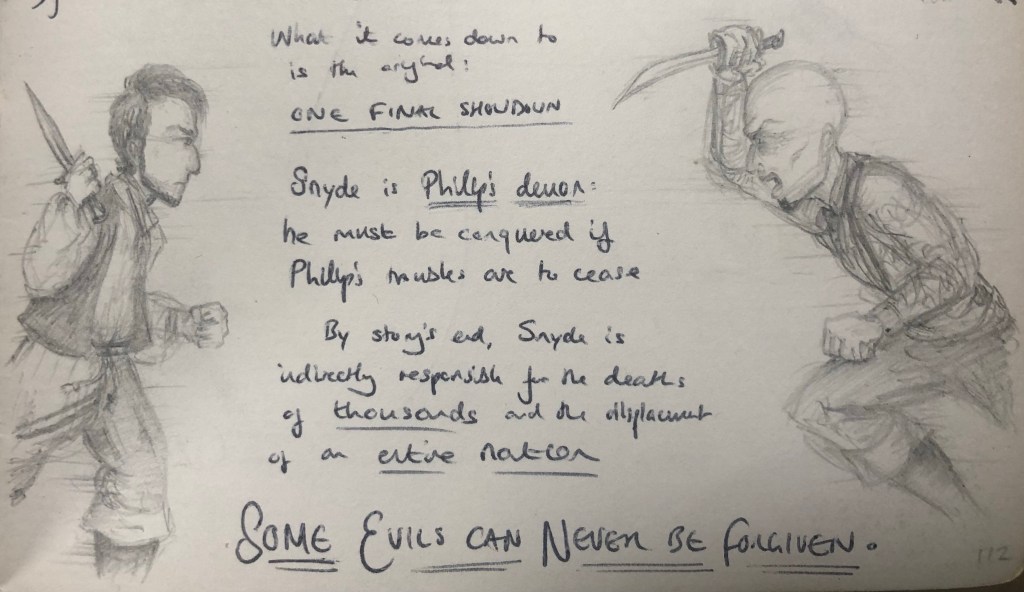

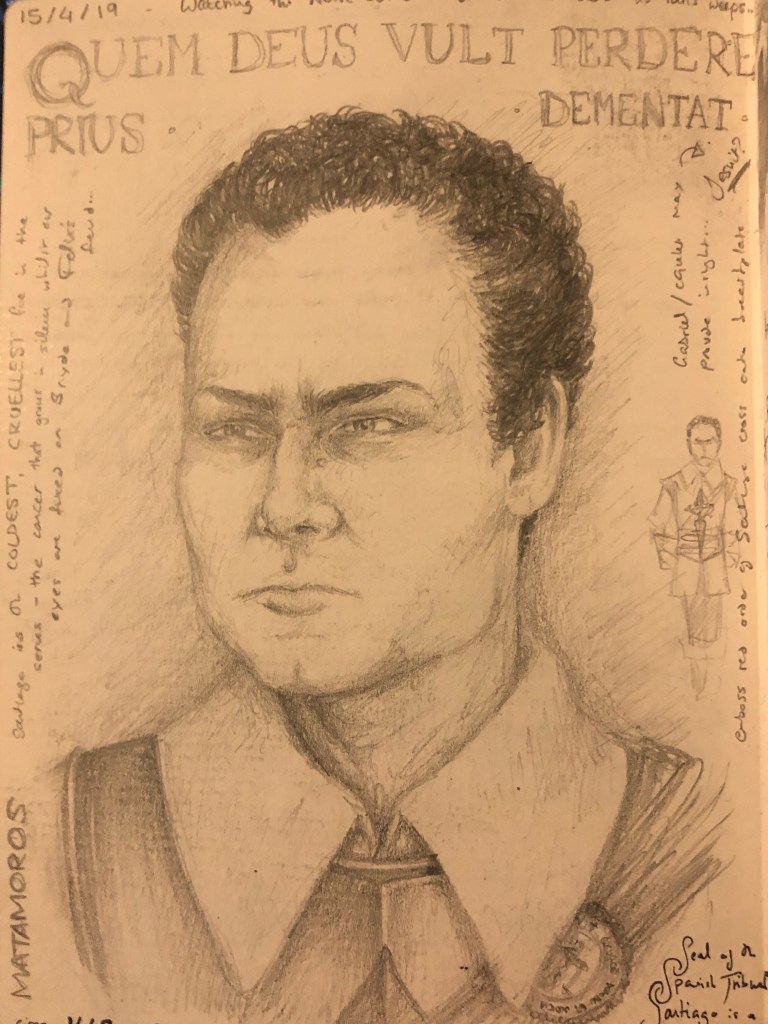

Unlike the heroes of my tales, the primary baddie has hardly changed since his inception. His wardrobe may have been updated a couple of times over the years, but his appearance has never shifted. The bald, skull-like head, the high cheekbones, the small black goatee and those piercing, eye-blue eyes… The latter have always seemed to me the most treacherous, wicked eye colour around, though that may have something to do with Daniel Craig’s early-career role as the fantastically sadistic Afrikaner Sgt Botha in The Power of One. Until very late in the Spanish rewrite he bore the name Jasper Snyde, and it was primarily the strength of his surname that held me back from Hispanicising the rest of the names in the book. It took a long time before I found a Spanish equivalent I was happy with. In the end I opted for De Salma, for the simple reason that, if elided (or spoken at the speed at which your average Spaniard speaks), it winds up sounding a lot like desalmada, meaning “soulless” – or, more literally still, “deprived of a soul”.

That’s right, middle school me. Authors do put that much thought into the names of their characters. It’s not just a trick English teachers play on you to get you thinking when it’s coursework season.

I think the thing I like best about Desalma is that he is nothing more and nothing less than a product of my own jealousy. Perhaps that’s why jealousy is one of his defining traits. Some villains you create to serve a purpose within the wider story arc, others are heroes who just weren’t good enough. Desalma is neither of these. He appeared fully-formed in a moment of weakness in my teenage years, moulded about an imagined rival for the attentions of a girl I had a thing for at the time. The crush didn’t last long, and the jealous rage that birthed him was even shorter-lived, but Desalma stayed, growing cancer-like from that first appearance into an evil that transcended all of the villains I’d written into my stories.

Like the Batman’s Joker, he wasn’t supposed to survive the story in which he first appeared, but over time his hold on me grew too strong, and for the greater part of the last decade he’s been the primary antagonist and tormentor of my hero. An avatar of desperation and despair to counterbalance’s the hero’s unyielding clutch on hope.

The other villains in the saga are, predictably, drawn from the other dark desires of my heart. One of my hero’s primary flaws was almost certainly one of my own in my younger years: that is, a magnetic hero worship of the tall, dark charismatic types who hold all the cards. The ones who have the looks, get the girls, crack the jokes and seem to have it all together. It was only too easy to morph the idols of my youth into adversaries whose intentions were not what they seemed, if only to repeat that old saying that has never lost any currency: handsome is as handsome does – or rather, looks can be deceiving.

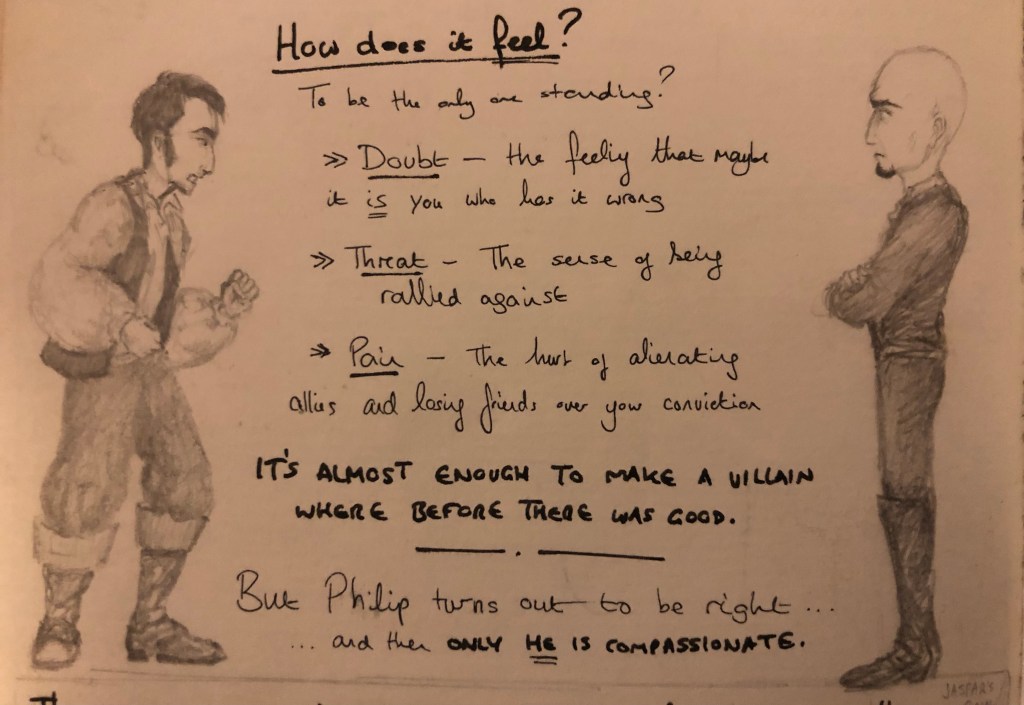

If I’m being honest, there’s been more than one occasion in my life when I’ve asked myself that question: wait – am I the bad guy here? It was especially poignant in my university years, where my tendency towards strong opinions and the sharing of said opinions got me into hot water with my fellow students. I found my views challenged so often, so vehemently, and seemingly by everybody else that, for a time, I genuinely started to doubt my own convictions. It’s so easy to start thinking you’re in the wrong when it seems like the rest of the world is against you. Israel. Free speech. Gospel music. No matter where I went, I always seemed to be on the wrong side.

Fortunately, most people aren’t walking around with a fictional universe that exists only inside their heads, and have long since learned to see the world through the mature eyes of a working professional adult. Perhaps it’s only those of us who cling to the world of good and evil, and light and dark, that insist on still making such a clear distinction between right and wrong. The grey in between is good enough for your average Joe.

I’ve been working on a new villain this week, between teaching the passé composé and marking Year 9 Spanish assessments. In recent years I’m much more inclined to letting my heroes suffer if it makes them into stronger characters at the end of it. I gave up on Ildefonso Falcones’ La mano de Fatima years ago because I lost all faith in the protagonist, but the more I read my Spanish histories, the more convinced I am that the world was a much darker place back then, just as Ildefonso Falcones painted it, and my stories need to adapt to reflect that. It takes a serious brush or two with the dark side of our hearts for us to see whether we have hero material in us or not.

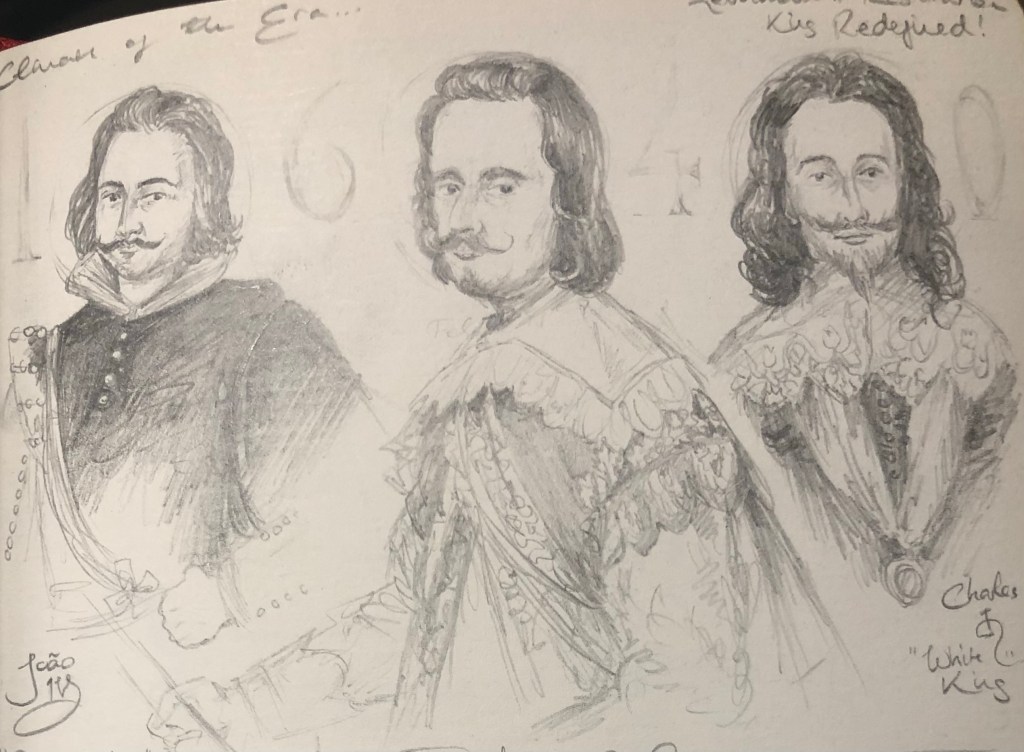

I’m leafing through Leanda de Lisle’s White King to clue up on the politics of Charles I (the Civil War era being contemporaneous with my saga), but also to glean some inspiration for a better-dressed baddie in the mould of a Buckingham or Richelieu. Desperados I have aplenty, and their motivations are easy to script: hunger will make a villain out of anyone. It’s the folks at the top I’m working towards now. Time, I think, for an exploration of power and its malicious influence.

Four years in, I think I have a much clearer idea of power. Because if you want to get a real handle on power, work in a boarding school. And that’s all I’ll say on the matter. BB x