Calle Especería, Málaga. 16.40.

There’s no two ways about it. I’m a total Semana Santa junkie. If it wasn’t for Semana Santa falling within the school holidays for the first time in years, I probably wouldn’t be here at all. Given the choice, I’d be nowhere else for Holy Week. Spain – and especially Andalusia – simply does Easter like nowhere else in the world. The only reason I haven’t followed a procession all night this time around is on account of being in a swarming city. One day, if God should see fit to grant me that privilege, I should like to take my uncle up on his offer and serve the family’s cofradía as a costalero. That would be the only way to put a seal on my obsession with this phenomenal custom.

I was only half an hour off the bus back from Gibraltar when I was back out on the streets to catch the Wednesday night pasos. I didn’t have to go far: the Brotherhood of Nuestro Padre Jesús “El Rico” y María Santísima del Amor had just left their parish and were looping back around the Plaza de Merced. The rank and file nazarenos were dressed in robes of deepest blue, but some of them wore white cloaks emblazoned with the red badge of the Order of Santiago.

In their train was a group of women in black, wearing the traditional mantilla, a gesture of solidarity with the grief of the Virgin Mary. Known as manolas, they are a relic of a time before women were allowed to participate in the usual Easter celebrations, such as wearing the capirote or carrying the pasos. Until as late as 1987, it was forbidden for women to don the hood, and it wasn’t until some time after that it became common practice for them to do so. These days, wearing the mantilla is something of a badge of honour for young women, knowing that they are keeping an ancient tradition within a tradition alive.

I allowed myself an hour’s respite – mostly to charge my phone – before heading back out into the night to see the processions by candlelight, when they truly come into their own. I was lucky to get a spot at all. Being such a major annual event, many malagueños know to stake out a spot early to get a good seat – quiet literally, in fact, as a number of the principal routes were lined with foldable deckchairs from eight o’clock in the morning!

Málaga’s guiris don’t seem to be huge Semana Santa junkies. By nightfall, they had mostly retreated to their hotels, leaving the streets to the locals. As such, with a couple of exceptions during the night, the dominant language in the street was that wonderfully ebullient andaluz, best spoken a gritos. My mother likes to collect sugar packets from cafés, and Spain has a quaint habit of decorating theirs with quotes. The only one that has always stuck with me is the incredibly Spanish ‘lo que vale la pena decir se dice a gritos’ (whats worth saying is worth shouting), which is probably one of the most Andalusian statements around. And to think I once found their accent impenetrable and annoying…! Heresy. Now it’s nothing short of music to my heart.

Another beautiful tradition of Semana Santa is that of the bola de cera. As the sun goes down, the nazarenos light their long candles – hardly necessary in a city as well-lit as Málaga, but an essential part of the spectacle. They need to be long to last the night, and it’s for this reason that the nazarenos all wear gloves, to stop the hot wax from dripping onto their hands.

In Andalucía, there’s another layer to it. Every time the procession comes to a halt, children run out into the street and ask the nazarenos for the wax from their candles.

They collect it on little sticks with a coin attached to the end – or using last year’s wax balls, if memory serves – and compete to see who can get the biggest ball of wax by the end of the night. It’s an old way of keeping the younger children entertained during the long hours of the processions, which usually go on well past midnight.

Honestly, it’s just incredibly endearing to see how wholesome this little game is. Sure, Spanish kids love their mobile phones just as much as (if not more than) English kids, but you don’t see a lot of English kids collecting wax or playing with spinning tops in the streets. I still have very fond memories of playing dodgeball and pilla-pilla in the streets with my friends when I was growing up out here. There’s just a bit more variety in the games that Spanish kids play. I want that world for my kids, if I should be so lucky to have children of my own someday.

There was a bit more of the behavioural policing tonight that I’m used to seeing in the pueblo: silver-staffed nazarenos striding over to give a ticking off to younger penitents who might have broken rank for a moment to gossip or talk with friends and family in the crowd. I’m always amazed by how quickly the nazarenos are recognised by their peers in the street, but then, if a ewe can tell its own lamb from its call alone, is it is so hard to imagine that a mother can tell their child from their eyes or gait? Perhaps not. We may not have the heightened senses of some of our animal friends but we are mighty indeed.

The one transgression that wasn’t being quite so closely monitored was the clustering of nazarenos around the glow of a screen at every stop – particularly in front of the Irish bar, where a large telescreen was playing the Real Madrid/Arsenal game. One nazarena was accompanied by her boyfriend, her black robes and his hoodie bathed in green light by the game on his phone, while a cluster of six nazarenos stopped to catch up on the replay, courtesy of one of the costaleros.

It was obviously an important game (what do you expect when Real Madrid are playing?) and it ended in a crushing 2:1 defeat for Real Madrid, but thanks to the greater task at hand of the procession, you wouldn’t have noticed. That said, I suspect that a Spanish victory might have been very noticeable: Spaniards don’t celebrate in silence.

To round out the night, a wing of the Spanish Army – specifically its Almogávar paratroopers – paraded by, accompanying their image of the Virgin Mary on her journey through the city. Lots of Spaniards come to town to see the Legion, but the Almogávares were a bloody good warm-up act, performing a number of impressive drills and acrobatics with their weapons as they marched.

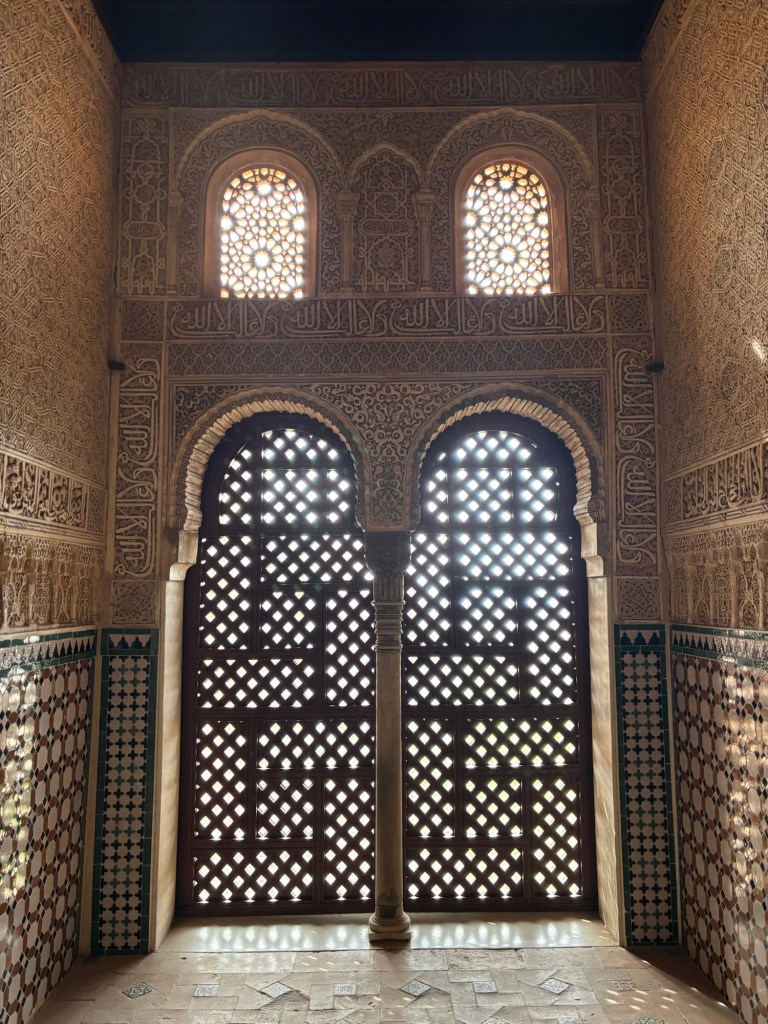

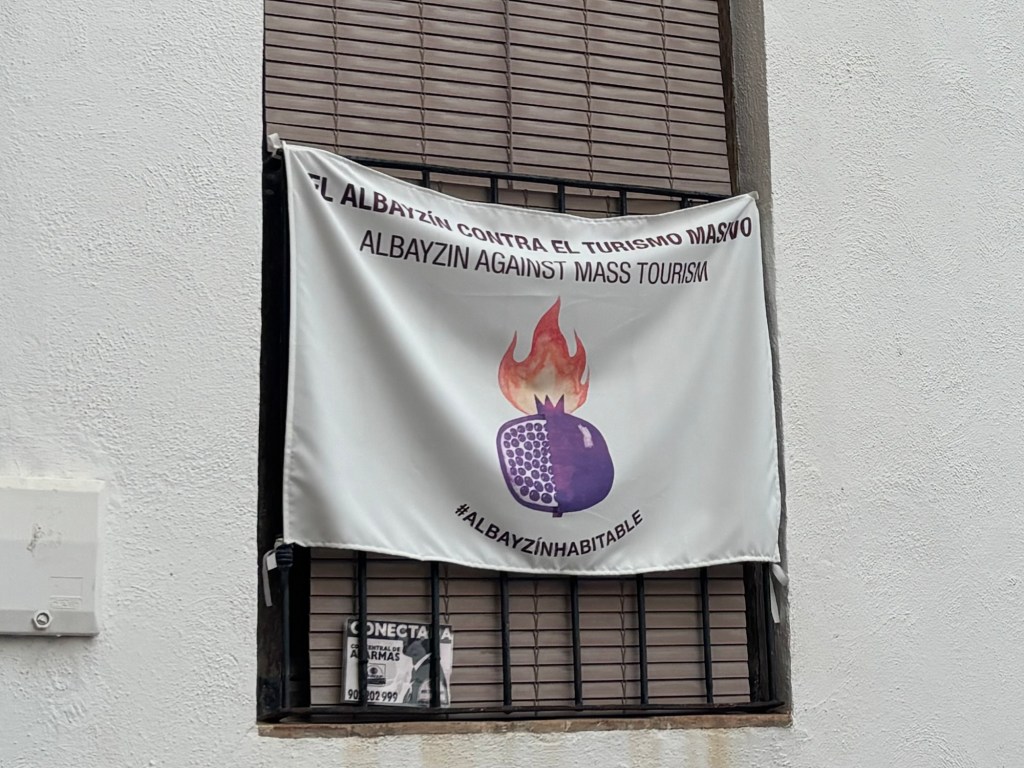

Like a lot of military terms – including our own admiral – the word almogávar is Arabic in extraction, deriving from the word al-mughāwir, a light infantry raiding unit used by both the Moors and the Spanish during the Reconquista. Spain owes a lot to its Islamic past, from saffron and stirrups to rice pudding and the police. Slowly, I think the country is starting to appreciate its coloured past a bit more.

I’d better leave it there, or I’ll have bored you stiff with Semana Santa stuff – and I’ve still got one more night’s work to report! So stick around – the best is yet to come! BB x