On Monday, I kick off my new role as the middle school gifted and talented programme coordinator with a lecture on the Aztecs. It wasn’t the obvious choice, as Mexico is a country I have neither visited nor researched nearly as extensively as my grandfather’s country. As a matter of fact I made a conscious effort to steer well clear of Latin American affairs at university, cleaving to the Iberian modules even when it meant the pickings would be slim. If Durham’s only Cervantes specialist hadn’t been on maternity leave in my final year, I could have stayed quite happily in my fairy-tale world of knights and princesses and Moorish warlords and binged on ballads, and I wouldn’t have had to go anywhere near strap-on wielding Catalans and metaphysical Madrilenians. Oh Quijote, en mala hora me abandonaste!

Ordinarily, for such a school project I would have stuck to my guns and wheeled out some Moorish magic with a talk about Islamic Spain, something that is close to my heart; or El Cid, a man whose legend (and whose 1961 movie) is embedded, thorn-like, a couple of inches deeper. I even briefly considered whipping up something about pirates, but I haven’t read nearly enough to do that one justice. Not yet.

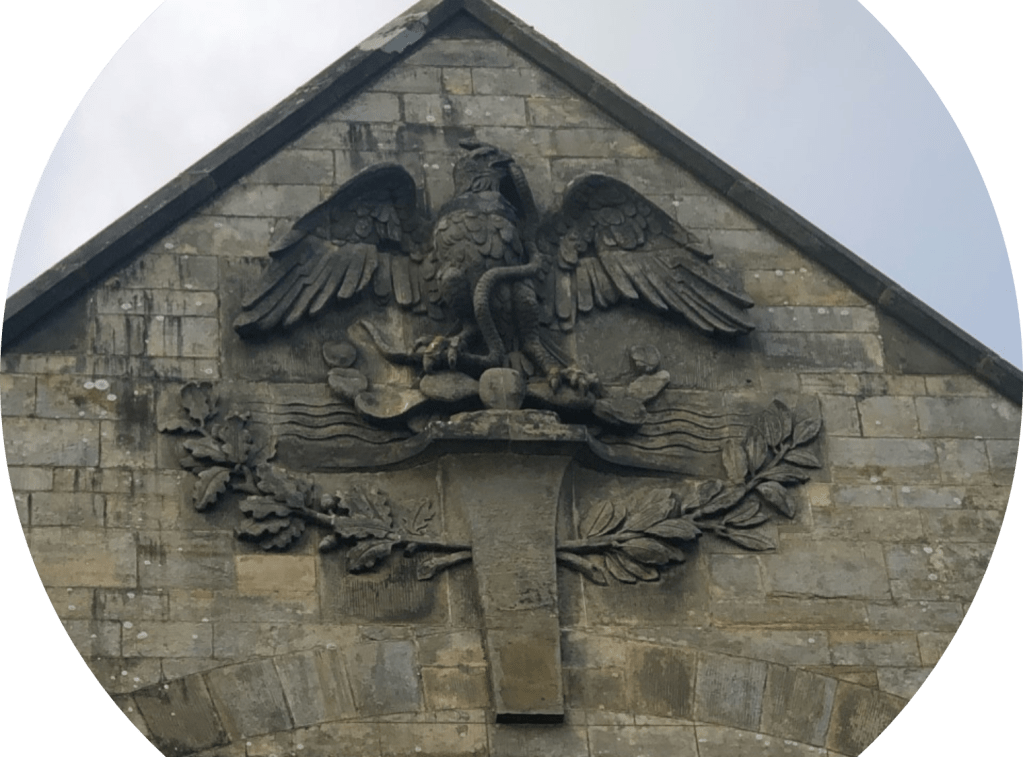

I landed upon the Aztecs for a couple of reasons. One, because the book I have chosen to read with my IB students is Laura Esquivel’s Malinche. Two, because my school – or rather, the people whose money built the house in which I now live and work – has a long history with Mexico, a connection that is plainly carved into the stone in several places.

But I think the main reason I wanted to explore the Mexica was because it ties me back, through the ruthless conquistadors, to a place that is still very dear to me: Extremadura.

My first contact with Spain was with Andalusia, with her jagged crags and whitewashed mountain villages. If I wasn’t spellbound there and then, my mum and dad must have been, because they made the crazy decision to up sticks and move us there in 2006… right on the eve of the financial crisis that was already driving many of Spain’s expats out. It might not have been the wisest move for three out of the four of us, but after a year of weekend hikes in the surrounding sierras, gecko-hunts in the streets by night, Holy Week spectaculars and vulture-chasing in the misty heights of El Gastor, I was absolutely hooked. Andalusia was my polestar for many years to follow, and her light shone brightest on the paradise of the tierras rocieras of Doñana National Park.

Over the years I braved her jealousy and flirted with her sisters: a school trip took me from Barcelona and the magical Mediterranean town of Tossa de Mar up and into the clouded dales of Cantabria and the foothills of austere Asturias. Legends of the Cid led me to Burgos and the empty plains of Old Castile, the guiding light of my ancestry led me home to la Mancha, and in recent years I’ve swum in the crystal waters of Mallorca and Menorca. Throw in flying visits to Aragon, Alicante, La Rioja and the Basque Country and it’s getting to the stage where there’s hardly a corner of the country I haven’t explored.

But I don’t think I could ever have anticipated the rawness of my obsession with Extremadura. From the moment I set foot on her soil I was lost. It honestly felt like falling in love for the first time. Not the high school crush kind of falling in love, but that kind of mature depth of feeling, that gut-wrenching, iron-tasting jolt in your upper body that tells you something’s starting functioning inside that was only dormant before.

Oh, cut the poetry already, BB. If you’ve been reading this blog as long as I’ve been writing it, you’ll know I didn’t actually talk like that when I arrived in Villafranca de los Barros on that hot September afternoon seven years ago. But hindsight is a wonderful thing, and any corner of the Earth that could convince me to jettison my plans for taking my teaching game over to South America for a second (and very almost a third) time must have an awesome power.

When Hernan Cortes and his men entered Tenochtitlan, one of the greatest cities of the world at the time, one of the things that shocked them most of all were the dreadful tzompantli, wooden scaffolds nearly two metres in height that carried between them the many thousands of impaled skulls of the sacrificial victims of the Aztecs. They came back to Spain telling wild tales of eagle warriors and war priests with matted hair and bleeding knives, and when one reads of the savagery wielded in the name of Castile upon the Mexica, it isn’t hard to understand why it’s been so popular until recently to discount the stories of tzompantli as a myth invented by the conquistadors to justify their actions. Until 2015, the year I moved to their homeland, when the bases of the huey tzompantli were uncovered in Mexico City, complete with row upon row of human skulls, laid out like so many candy calaveras on Dia de los Muertos. The conquistadors, for all their sins, must have had stories worth telling, if only people would listen.

Extremadura is one of those places I will probably write about again and again for the rest of my life. If Andalusia was my first crush, Extremadura was the lady who captured my heart for good. Not even the knowledge I have now that ties my bloodline more closely to Valencia than la Mancha can put a stain (no pun intended) on my devotion to her. Hers is a story I would tell and tell and tell until my tongue split in two.

Tzompantli: an image which struck no small amount of awe and fear. The presence of a God or Gods unknown (and a word that first threatened to split my tongue in two, but is now so satisfying to say that I have rather awkwardly made it the title of this post).

That is my Extremadura. Unknown. Disconnected. Hard to say. Trainless. Abandoned. The conquistadors couldn’t get out fast enough. Malaria festered in her hidden valleys long after it had been extirpated everywhere else, and the Mesta virtually enslaved her very earth to their will, subjecting her people to centuries of poverty. But it is precisely because of these fascinating tales – coupled with her unparalleled natural beauty – that I do believe Extremadura to be the jewel in Spain’s crown.

And oh, look – I started writing about Mexico and here we are, back in Spain. I’m nothing if not predictable. Some of us spend our lives traveling in search of that “something” that is just beyond our reach. I count myself amongst the lucky ones who found what I was looking for and need look no further – at least, no further than the light that shines on Spain’s shores. I can only hope Doña Extremadura forgives my curiosity.

Did Rodrigo, last of the Visigoth kings, truly disappear in her mountains after the fall of Merida? Did an army of ants reduce one of her villages to rubble? Were there really hordes of dwarves in Las Hurdes who descended into the valleys by night to terrify the locals? And what made Carlos, supreme ruler of the Spains, the Americas and all the Hapsburg Empire decide to spend the last years of his life in her wooded hills?

You will only find out if you go. Don’t hold on too tightly to your heart. BB x

P.S. Thinking about sharing some more stories from this part of the world… watch this space.