London Heathrow Airport, Terminal 5. 19.45.

The Camino isn’t truly over until you’ve made it home, so here I am on the 19.50 from Heathrow’s Terminal 5. It wasn’t the best welcome back to England. Somebody pinched the flip-flops from my bag. They weren’t exactly in the best condition and frankly I could care less, but it’s the principle of it. Six weeks of relatively careless travel across two countries and the first item stolen from me is within minutes of landing back in the UK. Add to that the grey hellscape that is Heathrow, the cost of just about everything, and the facelessness of London…

No. I don’t want to think about that. Not right now. My nerves are shredded enough as it is. I want to think about where I’ve been. Who I’ve met. What I’ve learned.

Nearly six weeks ago, I locked myself out of my flat, caught a late flight to Bordeaux and set out for the Spanish border with little but a few spare clothes and my journal. I did not know quite what to expect from such a last-minute decision: it had been a toss-up between the miserable money-sink of more driving lessons or a second Camino, and after a stressful year in a new school, the decision was just too easy.

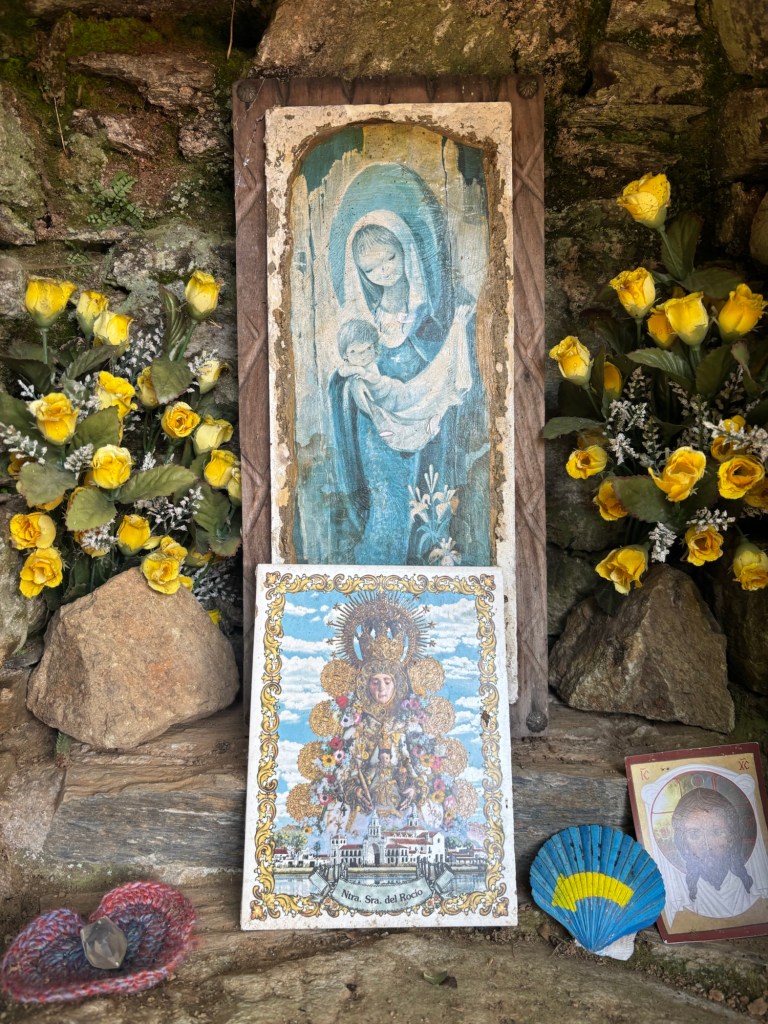

My reasons for setting out upon the Camino this year were varied. I had an uncommonly wonderful holiday in Spain at Easter and wanted to say thank you. A dear friend lost her father and I promised to pray for him at every church I found. I needed some healing after last summer’s heartbreak, which was mostly healed in El Rocío, though this wound has proved difficult to recover from fully.

I also needed to get away for a while. Social media has been leering at me with a stream of weddings of old friends, and with each one, I am reminded of how much I have been forgotten – or rather, how much I have allowed myself to be forgotten by going radio silent and burying myself in my work for the last eight years. I am still coming to terms with what I am now fairly certain is my undiagnosed ADHD, which came to a head somewhat this year, and would go some way to explaining much of my behavioural quirks and communication issues. I ended the year on a major high with the triumph of my new funk band – something I’ve wanted back in my life for thirteen years – but I still needed a change.

I come into my own on the Camino. There’s no pressure to communicate, but so much reward for doing so. Fleeting but powerful friendships based on shared adventures and the sharing of stories. A chance to swap languages constantly, and to learn new things about myself and the world each day. A chance to be back in my grandfather’s country, and to feel his spirit at my side. To walk in the light of the Blanca Paloma and to see the wonders of her world. To patch up the wounds in my lonely heart with an alchemy of golden fields, griffons and the churring of nightjars. To sing, to write, to read, to tell stories, to laugh, to walk, to climb, to run, to swim and to be surrounded by the one thing in this world that has never let me down: nature.

In short: to walk the Camino is to be myself.

When Gust left this morning, I was the last of us left in Santiago. I have been incredibly fortunate this year with my companions, who have been the most wonderful company – even for this lonely wanderer who so often set off on his own to walk the road alone, for days or even weeks at a time.

Alex. The lawyer. My fellow countryman. Lost to us far too soon in Burgos. In many ways, the one who brought us all together. You set the pace – sometimes too fast for even me to catch up. You came to my defence against the Dutchman and his beer-fuelled football rant. I would have walked with you to the end.

Audrey. The marine biologist. The trooper. A seeker of solace and of silence, with a kind word for everyone and a pure heart. This was your Camino, I feel. The rest of us just fell into orbit. And who could resist the gravity of such a warm disposition? I hope you found the peace you were looking for in the shining Aegean Sea.

Talia. The neuroscientist. The brains of the operation and the questioner. Sage and sober and endlessly perceptive. You awoke in me an awareness of paths untraveled that I had long ignored, shining more light upon the road than any headtorch-wielding peregrino – which I, in my preference for the starlit dark, sorely needed.

Alonso. The diplomat. The wanderer with a thousand-yard smile. Powered by kudos and watermelon. Chasing the Sun across the horizon “for the bit”. Your wits were almost as fast as your Strava-fuelled sprints down hill and mountain, and you brought humour to every town and village we found. 100%. For you, the journey goes on.

Chip. The agent. The sunniest Salt Laker this side of the Atlantic. Friend to the saint, the sinner and the sandhill crane. Fountain of wisdom and wit and the only thing holding me back from being the eldest of the family (for which I was very grateful!). We never did get to say goodbye, so perhaps I will have the chance to say hello there again someday.

Gust. The drummer. The free-spirited Waldorf wayfarer. Blighted by blood blisters, broken sandals and Italian blessings and still one of the bravest of us all at seventeen years of age (or eighteen, if your credencial was to be believed). A chip off the old block who slept in a bus shelter to secure an earned Atlantic sunrise. You give me hope.

I’m already thinking ahead to my next Camino. I love the sociable side to the Camino Francés, but now that I have done it twice, I feel it may be time for a sea change. The Camino Mozárabe is calling to me, looping through the marbled hills of Andalusia and winding across the green fields of Extremadura. I don’t think I’d be likely to meet such an excellent and eclectic cast as the one with which I have shared the road for the last six weeks, but it would be another genuine adventure – as the Camino Aragonés, the Primitivo and the San Salvador were this summer.

Of course, for the same budget, I could probably have a week’s holiday somewhere really exciting: a tiger safari in India, chimp-tracking in Tanzania or an adventure around the deserts of northern Mexico. But would it make me as happy as another five or six weeks in Spain? Probably not. I know what makes me happy. Happiness has a name and her name is Spain.

Well, I’m back in England now. But the story isn’t over. Not yet. I’ll be back tomorrow to muse a little more. I just wanted to put some thoughts down while the memories are fresh in my mind. BB x