Albergue de Peregrinos, Berducedo. 17.10.

I have acquired a nickname on this Camino: the Grasshopper. It makes a bit more sense in Spanish, where the name literally translates as “mountain-leaper”. Evidently Hispanic grasshoppers are better at jumping than English ones. Well, not this one, anyway: I took the mountains today at something between a run and a hurdle, leaving the other peregrinos in the dust. I wasn’t in any particular hurry, as I’m still ahead of schedule, but let’s just say I didn’t want to end up walking another 40km day after yesterday’s fruitless endeavours.

Well – mission accomplished!

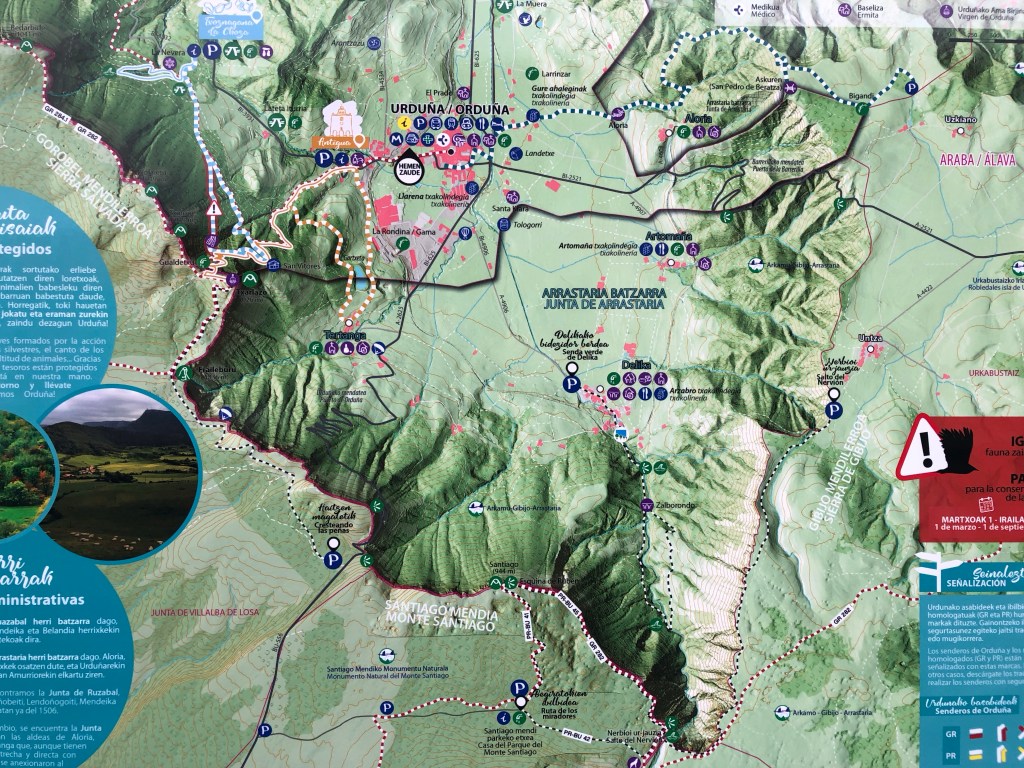

All the guidebooks indicate that making it as far as Pola de Allande puts the famous Hospitales route out of the question. Fortunately, that’s a load of nonsense. If you’re prepared to do some serious climbing, there’s a farm track that leads back up the mountainside, and I was more than prepared.

And so, as the Fellowship of the Ring tackled Caradhras and the Redhorn Gate (exceptional timing), I hurled myself at the mountain.

Uphill would be putting it lightly. Let’s just say that the company had already left Moria by the time I reached the top. But was it worth it? 100%. It wasn’t exactly the cloud sea that you get from the summit of O Cebreiro on the Camino Francés – which is around the same elevation – but it was a spectacular sight: pillars of golden light falling upon the green hills of Asturias to the east, dark forests of pine weaving through the valley floor below like a monstrous snakeskin, and great waves of clouds surging up the mountainside to break like water at its peak.

Standing here, upon the heights of the misty mountains, it was easy to see where the painters of Biblical masterpieces of old got their inspiration. Who wouldn’t be inspired with some sort of religious ecstasy in the high places of the world? Are not the mountains the closest we can get to the Heavens?

It’s still quite a schlep even when you’ve made it to the summit to reach the point where the Hospitales route joins up, so I had a fair stretch to myself. Me and the wild horses, that is, which were just about everywhere the cows weren’t. It must be a pretty charmed existence for them up here: all the fresh grass they can eat and all the space in the world, even if it is tremendously vertiginous…

After passing the ruins of the old pilgrim hospitals, I caught sight of the first peregrinos of the morning – mostly the crowd of twenty-odd who had reached Colinas de Arriba before me yesterday. Not to be outdone once again, I picked up the pace and vaulted past them. It’s hard to explain, as I don’t come from a particularly mountainous part of the world, but I have always been pretty nimble on my feet in the mountains, so there were large stretches where I confess I really was jumping from boulder to boulder. It feels right, somehow, in a way that a jog around the school grounds just doesn’t match. To think how fit and healthy I would be if I found a way to live in this country forever…!

The descent from Monfaraón was mightily steep, but then again, so is tomorrow’s descent to the Embalse de Grandas, so I looked at the exercise as good practice. The Camino climbs (or races) through the slumbering mountain villages of Montefurado and Santa María de Lago, and by the time I’d reached the latter I had put at least half an hour between myself and the last pilgrims I’d encountered on the road.

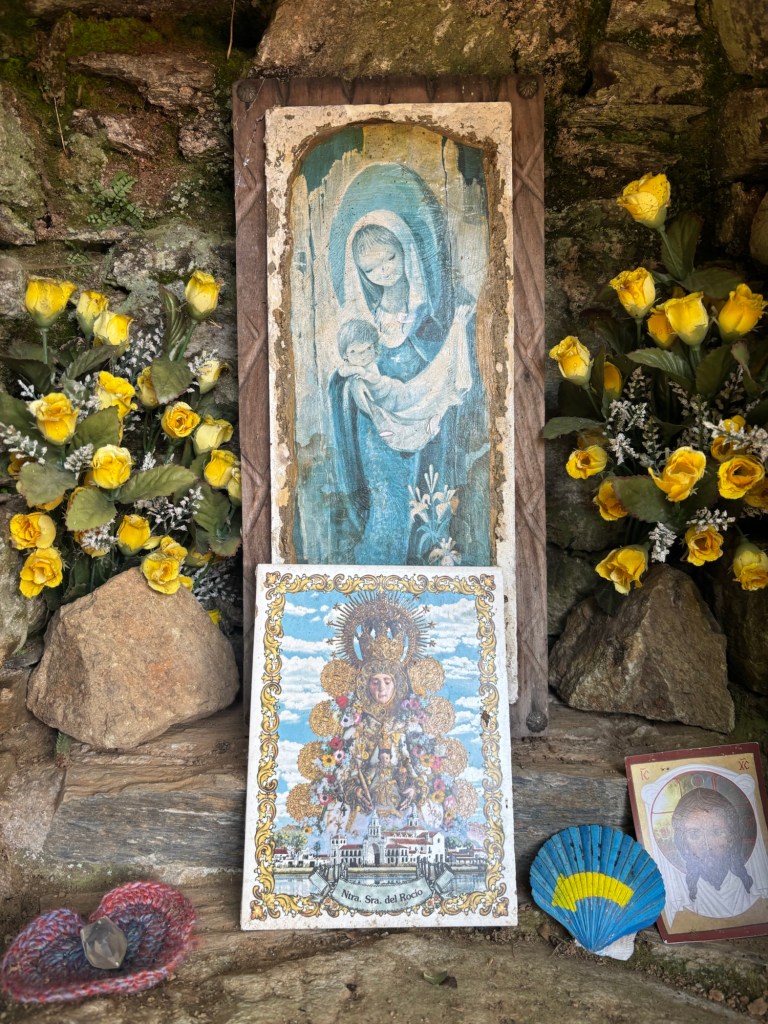

I didn’t see anything of especial note on the wildlife front beyond a veritable army of Dartford warblers in the heather on the mountaintop, but I did find a small shrine to the Virgen de Lago, in front of which somebody had placed an icon of the Blanca Paloma, which was a definite highlight. She has been a real guiding light on this Camino and my hearts soars whenever I find a space where she is venerated.

I got to Berducedo at around 11.40, all of an hour and a half before the albergue was due to open, so I could have pressed on – but after yesterday’s adventure, I wasn’t taking any chances, so I staked out the albergue and scored the first bed. A small victory, but one well-earned.

Not for the first time on this Camino, I bamboozled the other pilgrims by speaking only in Spanish and with a very thick southern accent which, I’m told, smacks of “La Línea o algo” – a mix of English and Andalusian, but more Spanish than English, which is plenty good enough for me.

I had lunch with a large group of Spanish pilgrims from all over: León, Toledo, Donostia, Madrid and Andújar, as well as an English lad here brushing up on his Spanish before the trials of Year 13. The fabada was phenomenal, and should give me all the energy I need for tomorrow’s mad trek, as I need to gain a day or two somewhere between now and Santiago.

There’s an Italian girl who is in tears because she can’t go on. One of the Spaniards is gently encouraging her to look after her health and to come back when she’s ready and pick up where she left off. She’s not the first casualty I’ve encountered on the Camino this year and she won’t be the last. I have to count myself lucky that I’ve made it so far in such good health. Maybe my daily prayers are doing some good for me after all. BB x