Bristol Temple Meads, 9.02am.

The May half term is drawing to a close. I’ve stayed put for a change, using the time to mentally decompress after another very busy term. Four weeks remain of the school year, and while there’s not as much teaching going on, it’s still going to be an intense gauntlet of exams, reports, events and rehearsals. I’ve done a lot of much-needed spring cleaning, idle Camino planning, bouncing ideas off ChatGPT and now, a little stir crazy, I fancy a day out. So I’ve grabbed some Y8 marking and a few books (Adrienne Mayor’s The First Fossil Hunters is my current obsession) and I am now on the train bound for Oxford.

Why Oxford? Partly because I haven’t really been to Oxford before. I was there two months ago for the Oxford Schools Finals Day, but as I was leading a school trip I didn’t really have any time to appreciate the city for itself. It’s also partly for the Museum of Natural History, which is supposed to be exceptional (I never did grow out of the dinosaur phase). But it’s also because over the last few days I have started to flirt with the idea of a possible career change: setting my teaching and boarding duties aside to pursue a Master’s degree in Medieval Studies.

There’s a couple of travelers next to me on the train having a very interesting conversation. They are a curiously paired ensemble: one, with a patchy beard, AirPods in and his shirt unbuttoned to the sternum, talks in a streetwise drawl about how he stole a few cans of Red Bull from Tescos once, and how the worst thing in the world is that parents don’t discipline their kids right anymore – if he’d disrespected his dad, he’d have “had a black eye”. He drops his T’s in the words right and football and drops F bombs in the gaps. The man next to him, a young Asian in a smart shirt with his sleeves rolled up nearly to his elbows, calmly (and without a hint of profanity) explains the difference between Asia’s bullet trains and the UK’s privatised public transport system (which he calls the public torture system), the importance of location when investing in property and celebrates a model aircraft he recently won at an auction. That seems to be their connection – they’re model plane collectors. I was beginning to wonder what could possibly tie these two together.

Why a Master’s degree? Why Medieval Studies? And why has the idea only come to me now, eight years after graduating with a BA in Modern Languages and Cultures? To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. A number of reasons come to mind. Citing my Y9 class seems churlish, but it’s probably part of the bigger picture of just how much of a gear change this year has been. Challenging and engaging, but occasionally uncomfortable. I suppose that’s only natural when you up sticks completely and change schools. Perhaps that’s why some teachers never leave.

It’s a little deeper than that. I do miss academia. I have always loved the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, and just occasionally, I find that hard to square with a job where success is so often scored against a mark scheme that shifts according to the national skill level.

I’ve just started to sink my teeth into A Level teaching, but I’m both disappointed and mildly alarmed by the lack of general knowledge of my students. Only one of mine could tell me what Scylla and Charybdis were, and that was a child in Year 10. I’ve had sixth formers before to whom I’ve had to spell out the story of Adam and Eve – we’re talking Catholic Europeans here, too – and mine was the only hand to go up in chapel two weeks ago when we were asked if we knew the parable of the man who built his house on the rock.

You could chalk that last one up to nobody wanting to look foolish putting their hand up in church on a Tuesday morning, but classical (and even general) knowledge of even the most basic sort seems to have fallen away by the time our kids reach sexual maturity. They all seem to know who Mr Beast is, though.

Something I wasn’t expecting in Oxford was the Pottermania. I deliberately haven’t waded in with an opinion on J.K. on here because, as with a number of topics, my thoughts are not in line with those of the rest of my generation. But one thing that is really quite depressing is that I ran into no fewer than five Harry Potter themed tours, pointing out turrets, windows and other locations used during the filming of the saga back in the early 2000s. It seems a little trite that tourists flock to a city that harbours one of the oldest universities in the world just to snap a selfie in the style of a still from a movie… I took a cohort of summer school kids on one of those trips once and they were deeply disappointed (I think they were expecting Harry Potter studios, not a Chinese woman with a ring bound pad of stills).

It’s times like this that I need a good kick in the shins – somebody (besides myself) to call me out for being so judgmental. Maybe that’s something I miss about university, too.

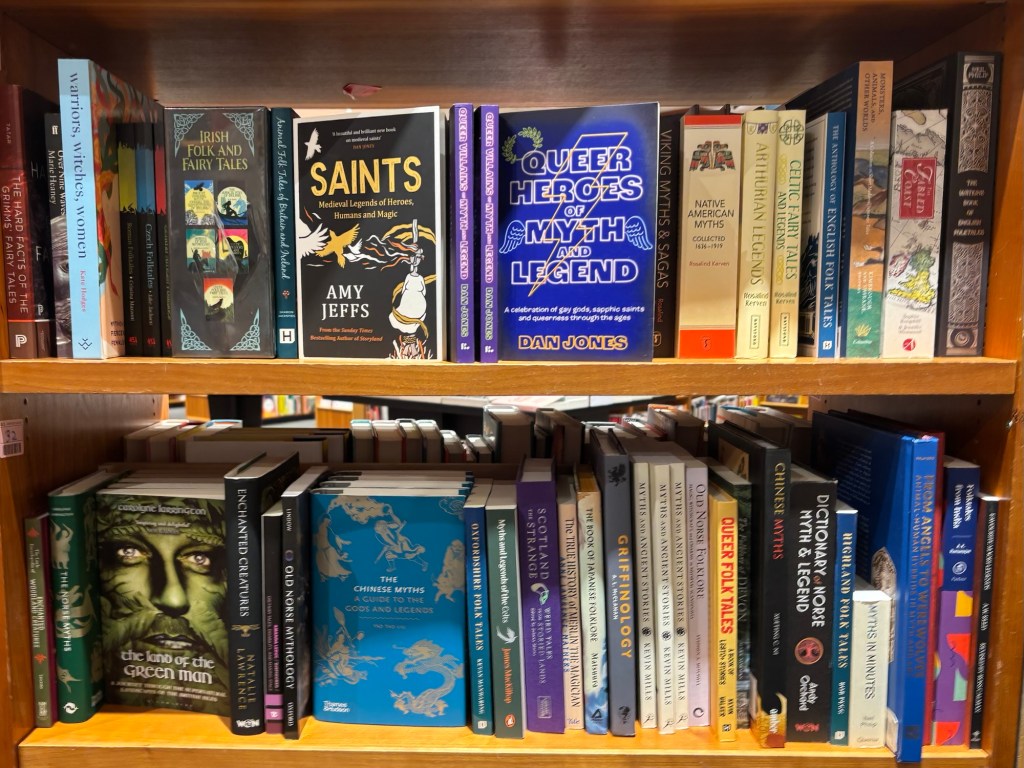

Before checking out the museum, I explored Blackwells, Oxford’s famous bookstore. The shop is particularly well-known for its Norrington Room, a literary Aladdin’s cave beneath the city that seems to have everything. I made a beeline for the Mythology and Folklore section and looked for anything Iberian.

Nothing. Tome upon tome on Norse mythology, endless volumes of British folktales, a beautiful gold-bound compilation of the tales of Anansi the Trickster and no fewer than five collections of Queer Fairytales – whatever those are – but nothing on Spain or Portugal. Nothing at all. Even Google didn’t seem to have anything.

Spain isn’t lacking in colourful folklore of its own. From my reading, it’s apparent that the combined efforts of the Almoravids, the Almohads, the Spanish Inquisition and Franco’s regime weren’t able to snuff it all out. But the literature simply doesn’t appear to exist.

I think somebody should write about it. And I’m starting to think that somebody should be me. Oxford University has a Masters course on Medieval Studies that occasionally covers Iberian founding mythology – the subject I chose for my undergraduate dissertation – and that just might be the way in… if I can get in.

I’m not really Oxbridge material. I got as far as an interview at Cambridge, but my meekness was torn to pieces in the French interview – and I really haven’t read enough of the classics. But I have read a lot of books.

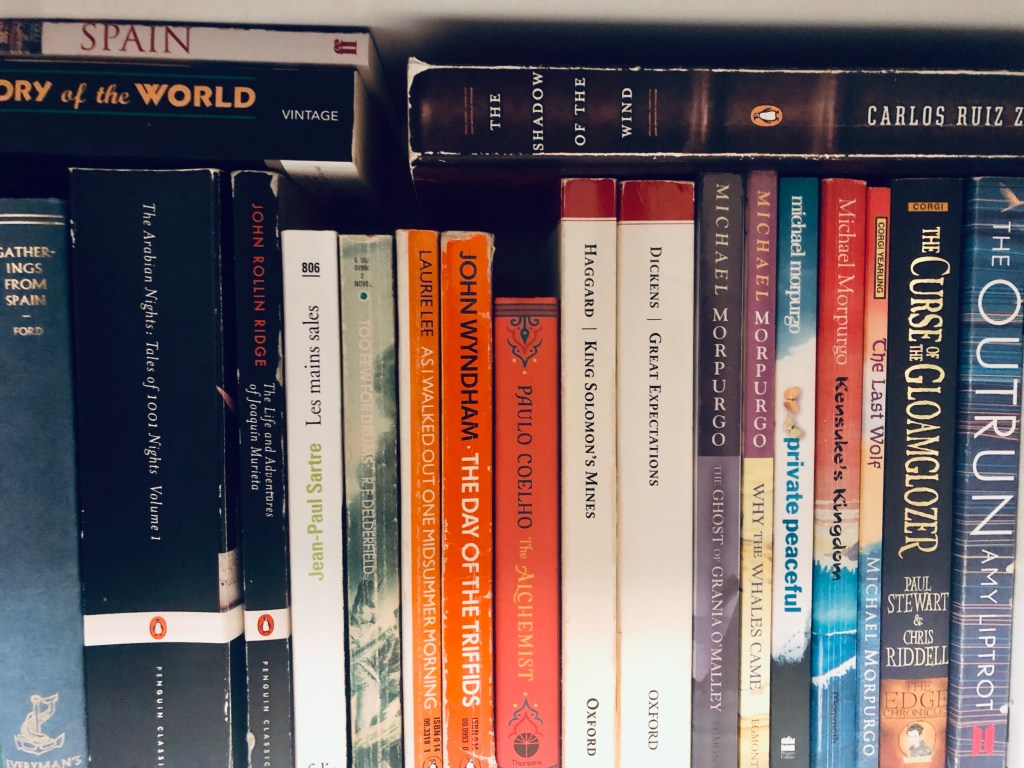

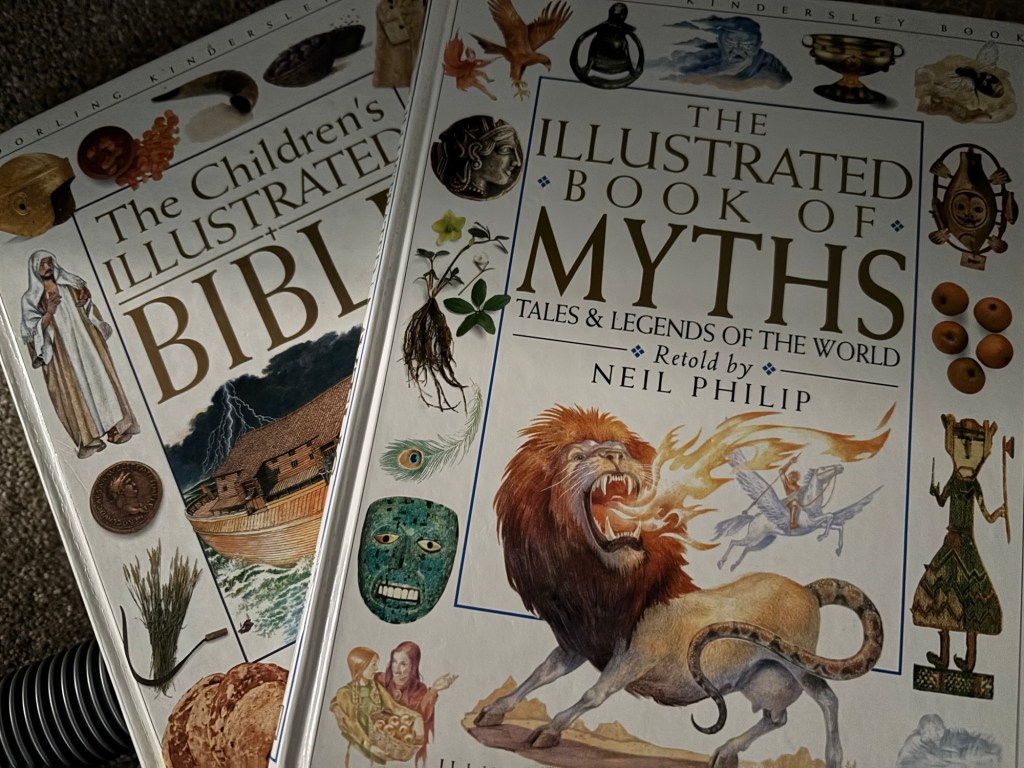

I grew up on a privileged diet of literature. We had more books than anything else at home, largely on account of the fact that my mother rips through books in a single night and was thus always on the hunt for a replacement. The bookshelves in my bedroom were (and still are) crammed full of colourful dinosaurica, but sandwiched in among them was a mountain of mythology and a feast of fantasy. My mother may not have been an outspoken supporter of “fantasy shite” but she did encourage my voracious reading habits. And I know my Dad used to read to me a lot – he even read the Harry Potter books to me when they first came out.

Neil Philip’s Illustrated Book of Myths played an especially large role in all of this. Atticus the Storyteller had a similar hand (and, to a lesser extent, the Age of Mythology games), but the colourful illustrations in the Dorking Kindersley compilation made it especially impactful. I must have spent literal days poring over the pictures in that book, cramming my childish head with stories of Athena and Anansi, Izanagi and Izanami, Glooscap and Gilgamesh. All tremendously important things to know – and none of it serving any practical purpose beyond the pages of the book where they were written. I haven’t even been able to use much of it in the odd pub quiz, which seem to rely on a more grounded understanding of Emmerdale and the last FA cup final than the exploits of Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

If I’m lucky enough to have children of my own someday, I will read to them from that book – even though I know most of the stories by heart. The pictures are so beautifully illustrated that I can see most of them still when I close my eyes, though it may be over twenty years since I last saw them.

Stories are how I make sense of the world. I’ve been writing stories for as long as I could write my own name. There’s not an awful lot of call for storytelling at work, but I do my best to share them with my students when the curriculum allows.

And it’s taken me a long time to realise that, after Spanish interest and natural history, the third largest collection of books in my library is all folklore and mythology – the oldest stories in the world.

Maybe – just maybe – I’m scratching the surface of the real me. I did always want to be a writer. I just didn’t ever think I could do it.

I’m still unsure. So much of my identity has been built upon the rock of being a teacher, and casting off those robes to dive into the world of myths and legends seems… well, childish at best, selfish and reckless at worst. And there’s the question of stability, job security, money and the fact that all I really want to do is find the One, raise a family and tell stories. But the void in all those bookshops is tremendously loud. Stories that aren’t told will eventually disappear, taking their worlds and their characters with them. It would be a terrible shame if the generations of the future looked back on our time and accused us of letting the ancient wisdom of the past slip through our fingers while we were so violently hypnotised by the bewitching glare of this or that Pied Piper of Instagram.

Who will remember Mr Beast five hundred years from now? What stories will they tell of him? Will his legend amaze and inspire, or will it push more and more children toward the worship of Mammon? I worry about that. I worry about that quite a lot.

I’ll give it some more thought. These are not decisions made lightly. The Camino will provide. It always does. BB x