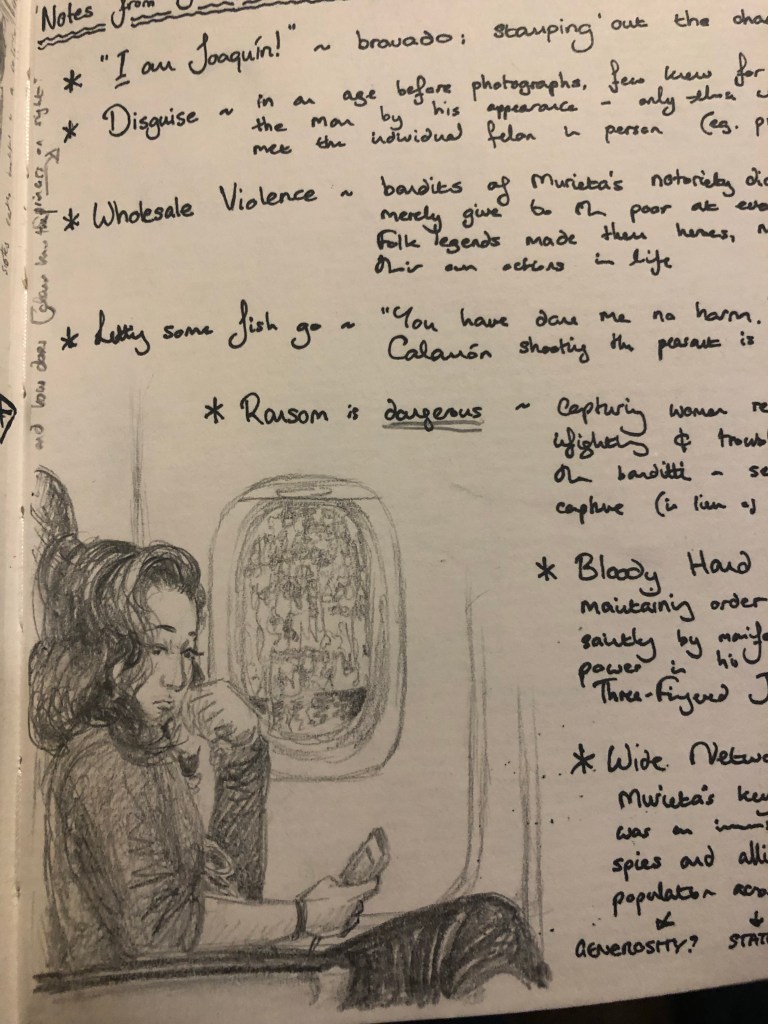

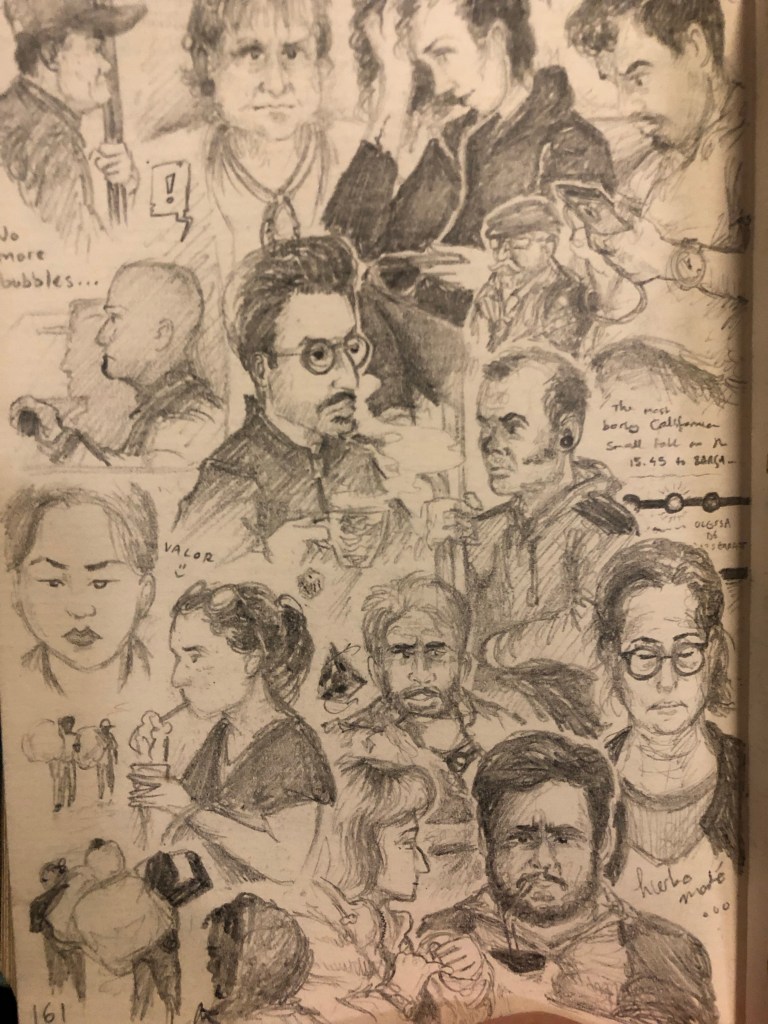

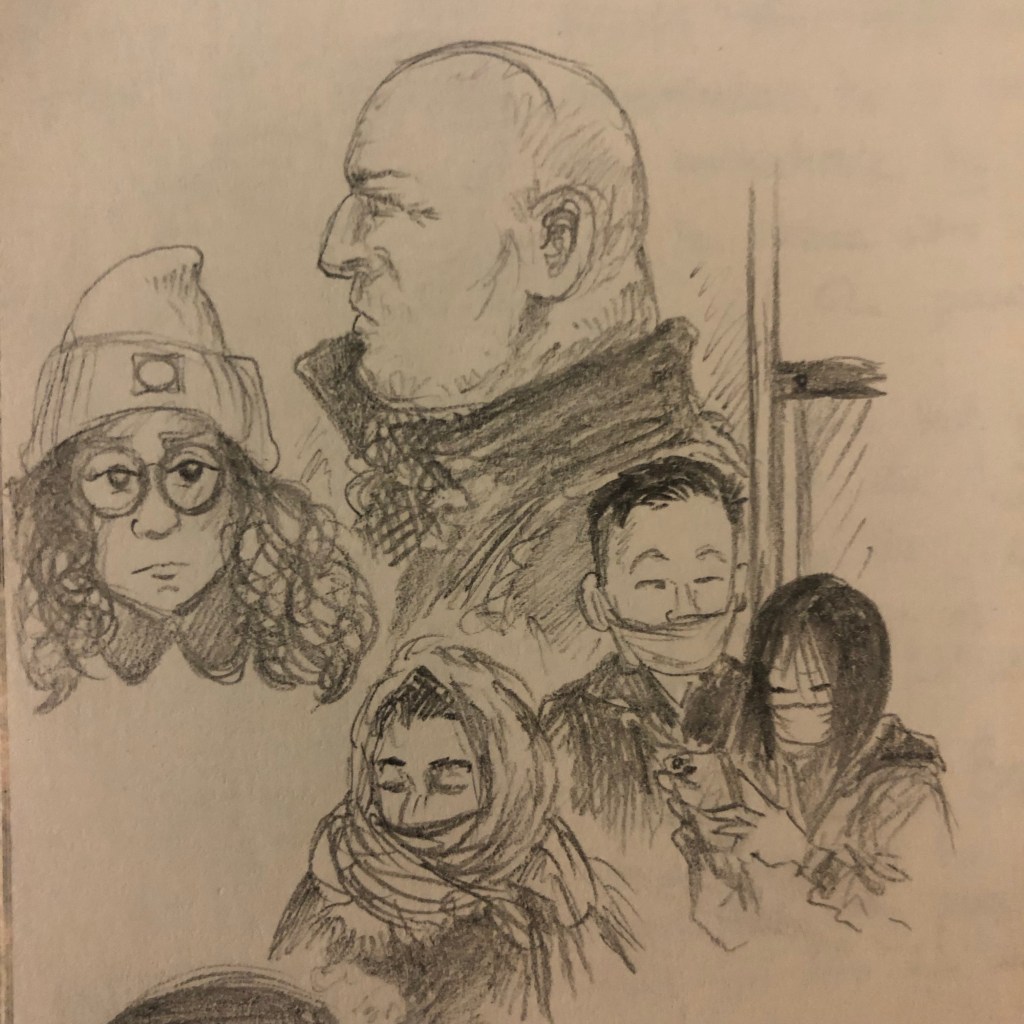

I got the train up to London today with a view to getting my hands on a decent pair of shoes, since I’m told the Italians can be a little snobbish when it comes to standards of dress. With the Northern Line under repairs, it took a little longer to get up to Bloomsbury, so I took a leisurely ride on the Circle Line from Blackfriars and indulged in a favourite pastime: sketching commuters on the Underground. There’s an art to it (no pun intended) – you’ve got to be quick, since most of them only travel a few stops before getting off. And now that face masks are a minority affair, it’s a lot more enjoyable a practice than it was.

Predictably, I got waylaid in Gower Street’s Waterstones en route to the shoe shop. Ever on the hunt for new additions to my Spanish library, I thought I’d do some digging at one of London’s finest bookstores, since it’s been quite a long time since my last visit. I managed to exercise a considerable amount of restraint this time, leaving behind two case studies on the Inquisition from the antiques section in the basement and Minder’s The Struggle for Catalonia… though I’ll be back for that one eventually. Giles Tremlett has brought out a new book on Spain which looks like it will pump out a lot of material I can use with my A Level Spanish students, which is my way of justifying that purchase. The only book I didn’t question was an account of Walter Starkie’s Camino. Starkie wrote so vividly about his journeys as a minstrel across Spain in Spanish Raggle Taggle and peppers his writing with old verses all over the place, so I had to salvage that one.

I wandered down towards Oxford Street in search of a decent pair of shoes, but I couldn’t find anything that jumped off the shelves at me, so I decided to make do what I have (a fine piece of advice at the best of times, which I wantonly ignore whenever I should be near a bookshop) and cut across town back to the river through Soho.

I’ve either forgotten how luridly seedy Soho is, or I haven’t properly explored the place before. What looked like a shortcut led me down a dark alleyway with shady adult stores on either side. The noise of Oxford Street seemed to die in the distance, like the record player in the Waterstones’ basement, stifled into silence by a wall of books… only now by grimy bricks and a mere sliver of sunlight through a gap between the buildings above. I almost collided with a stocky man in a big puffer jacket with a cough came lumbering out of a film store, stuffing something under the sleeve of his coat. Two Arabs stopped talking and gave me a funny look as I passed, clutching my journal in one hand and one strap of my rucksack with the other, humming the tenor line from Ola Gjeilo’s Northern Lights to myself. I guess Soho isn’t on the tourist trail.

Leaving Soho behind, I wandered through the crowds in Chinatown and came out onto Trafalgar Square, where a large crowd had gathered on the steps. Unsurprisingly, it was a rally against the war in Ukraine. Blue-and-yellow flags fluttered high above the throng, joined here and there by Polish and Hungarian partisans adding their colours to the mast. One woman, the tryzub emblazoned on her cape, stood defiant at the front of the congregation, fist raised in a powerful salute for most of the half-hour I stuck around to watch.

Boycott Russia.

Arm Ukraine.

Stop Putin, stop the war.

Those were the chants, coming around and around before the crowd. The main speaker apologised for the necessity of being so blunt, before decrying the rape of Ukrainian women by Russian forces and the slaughter of its children. An Englishman spoke slightly hesitantly about the need to support Ukraine’s disabled and elderly refugees, and a Ukrainian began to sing a national lament as the sky darkened overhead and the sun faded from sight. I’ll admit I half expected there to be a police van lurked nearby, its officers on standby for any disruption, but I couldn’t find a visible copper for love nor money.

The last time I saw a demonstration like this was back in October in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, as I walked back to my hostel with one of my cousins. “They’re always here,” he told me, “and so are they,” indicating the loitering policia who hang back just shy of the crowd, silent, hands on their truncheons, watching the Republican flags flying in the night air. The crowd was surprisingly mixed: an old man in a flat cap stood shouting his passionate support in the centre of the throng, while two girls shared an equally passionate and equally political moment on one of the bollards. The policia watched on, silently.

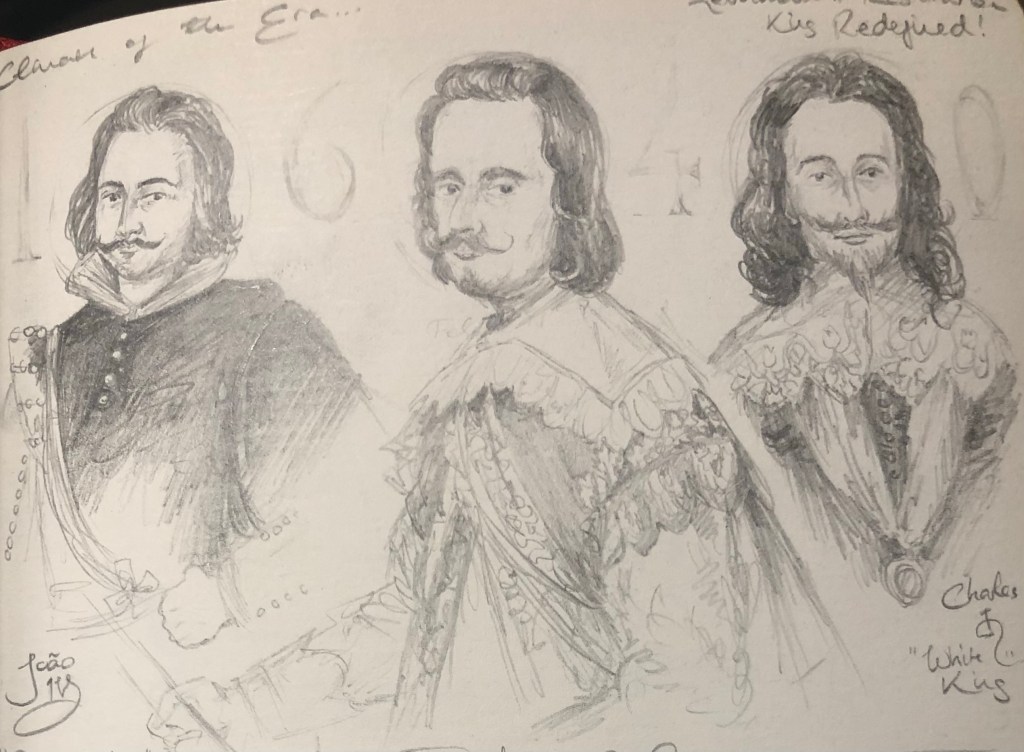

On my way back to the station, I stopped at the traffic lights and looked back to Trafalgar Square. Lord Nelson and a mounted Charles I stared southwards over my head, silhouetted against the clouded sky: two men who got personally involved in European wars and paid a physical price for their efforts. Little wonder, then, that the European powers are so reluctant to send any troops into open battle to defend the Gateway of Europe.

Back at Blackfriars, the rally seemed a world away. I missed the early train by a whisker and had to wait twenty minutes for the next one. A Catalan girl sat on a bench nearby, a red-and-yellow skiing jacket from Cerdanya proudly displaying her winter colours. I instinctively reached for my face, but my usual rojigualda facemask was at home: I’d opted for a less nationalistic face covering today. Away to the east, the sun broke through the clouds over the Thames, lighting up Tower Bridge against the rainclouds rolling in from the south. London seems to go on forever, whatever happens to the rest of the world, and yet it’s Rome that holds the title of the Eternal City. I’m looking forward to seeing it with my own eyes and reading such stories as I can find in its people and its streets. BB x