The Italo high-speed train races across the Ponte della Libertà, leaving Venice and its islands far behind. I’m bound for Rome, the Eternal City, my final stop in this first expedition to Italy. In what is possibly a crime against humanity, I’m skipping Florence this time, on the pretext that to spend anything less than two full days in Dante’s city would be to woefully undervalue one of Italy’s greatest treasures. Next time – and there will be a next time – I’ll come back for Florence, and Trento, and maybe even Milan. But since it’s my first time here, and my Italian is rudimentary at best, I’d rather depart with a hunger to return.

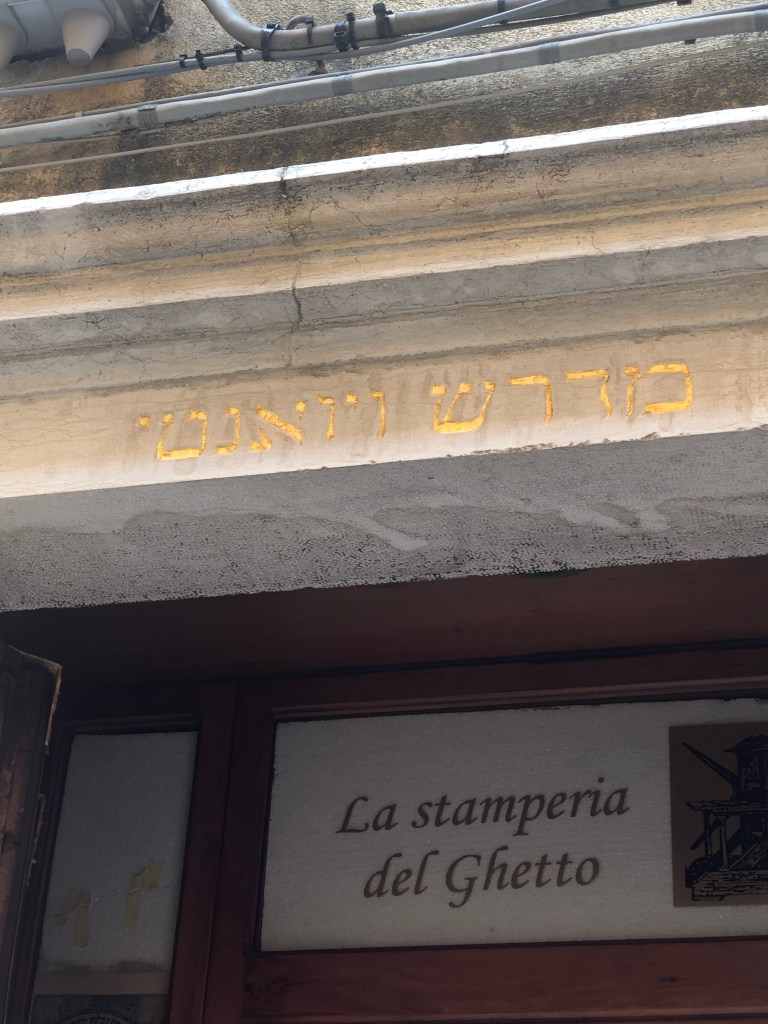

Far and away my favourite corner of Venice is the Cannaregio district to the north of the island. It’s marked with a Star of David on most maps, and it’s where you’ll find the city’s former Jewish ghettos (not in confusingly named Giudecca which, despite being a mangling of judaica, was never home to the city’s Jewish population). It’s a quieter corner of the city, dark and understated, but take a moment to stop and take stock of your surroundings and you’ll see some surprising sights – chiefest of all being the Jews themselves, hanging on tenaciously in the same corner of the city in which they were once corralled.

My contact with the Jewish world has been ethereal for the greater part of these last twenty-eight years. I played a Jewish tailor in Fiddler on the Roof and Klezmer stalwarts like Hava Nagilah and Tants, Yidelekh, tants (Dance, Jew, Dance) were my go-to violin pieces as a child, but that’s about as close as I ever got. Doubly so after Covid derailed my trip to Israel two years ago. To tell the truth, I could probably count on the fingers of one hand – two, tops – the number of Jews I’ve ever had a conversation with. So coming to Venice and seeing not just a sizeable but highly active Jewish community in the flesh has been nothing short of heart-stopping.

As usual, the Spanish connection was the real draw. Among the Italians, there are a great many Spanish surnames carved into the various memorials commemorating the disappeared and the dead. Morenos. Navarro. Vidal. Grim reminders of the centuries-long fate of the Jews, fleeing from one intolerant regime into the arms of another. At some point in their history, many of Spain’s Sephardim must have been faced with the painful choice: to abandon hope and their homes, or to abandon their faith. If the stories I do so want to believe are true, then my ancestors made the bitter decision to remain under the unforgiving aegis of a Christian God, rather than leaving behind the land that had been their home for generations. Could you blame them for that?

As I wandered through the ghetto nuovo, I saw a Haredi gathering through a window. A boy stood outside the window, shawl at his waist, shuckling at prayer. A girl on the vaporetto at Murano had a gold necklace bearing the Hebrew letter he (ה). Out in the backwaters of Burano, a man sped by on his boat as I ate my lunch, sidelocks flying in the wind. I didn’t expect Venice to be such a centre of Jewish activity, but it’s a miracle to behold.

My eagle eyes were trained on other things than just bird life and Hebrew paraphernalia. If you visit Murano for its glasswork, something you ought to do is go beach-combing by the vaporetto stop near the lighthouse. For one thing, it’s ridiculously easy to spend a week in Venice without ever touching the water once, and this is a very accessible point to make contact. For another, an island whose primary output is glass and clumsy tourists makes for a mudlark’s dream: scattered amongst the lagoon’s mussel and oyster shells you’ll find all manner of glass washed up on the shore. Who knows how old the shards are? Some of them might be decades or even centuries old. A great many more were probably dropped in yesterday by this or that day tripper who was careless in boarding the boats. Whatever their history, there’s a rainbow of debris along Murano’s shoreline that’s well worth a careful investigation, if you fancy getting your hands on some free if highly fragmented Murano glass.

With only a few hours left on the clock, I very almost missed Venice’s main attraction entirely. Despite passing St Mark’s Basilica every time I got off the vaporetto from Giudecca, I confess I hadn’t considered going in to explore at all, until the realisation that I might let my private feud with scaffolding debar me from seeing one of the most beautiful churches in Christendom finally got the better of me. And not a moment too soon – after my island-hopping excursion around the lagoon, I only just made it back in time for the final opening hour.

In short, I’m glad I did. It’s not free to enter like it once was, but 3€ is a pitifully small sum to pay to see the glittering Byzantine majesty that is St Mark’s ceiling. Heathen that I am, I don’t have a lot of time for Renaissance art, but there’s something about the sunken, staring eyes of Byzantine saints that I find absolutely spellbinding. And St Mark’s certainly isn’t short on saints.

Probably the most awe-inspiring part of the interior is the entrance itself – while you’re busy buying your ticket, don’t forget to look up at some of the best lit (and best preserved) of the basilica’s mosaics!

I lit a candle for my ancestors before leaving. My grandfather was a traveler, but I doubt he ever made it this far. So when I travel, I travel for him; just as when I write in my journal, I do so in memory of my great-grandmother. Traditions are everything. Insert your Fiddler on the Roof pun here.

To round out my stay in Venice, I took the lift up the campanile to see the city from on high. It’s worth the 10€ – the views are spectacular and it really helps to put your adventures around the lagoon in context, as you can see most of the islands from up there. There aren’t many cities in the world that aren’t eaten away at by modern cement monstrosities, so Venice is a city you should see from as many angles as you can. And since I didn’t have the window seat on the flight in, this was the next best thing!

The train is slowing down. We’ve cleared the long dark tunnel through the Apennine Mountains and left clouded Florence far behind. The group of four American travellers from Badiddlyboing, Odawidaho (right out of the frighteningly accurate Harry and Paul skit https://youtu.be/BGc3zFOFI-s) have finally stopped talking about Geoff’s wine tour and are playing Candy Crush in silence. Outside, the sun shines on Lazio, and I’m ready for the next adventure. Andiamo di qua! BB x