Casa Mamré, Jaca. 20.08

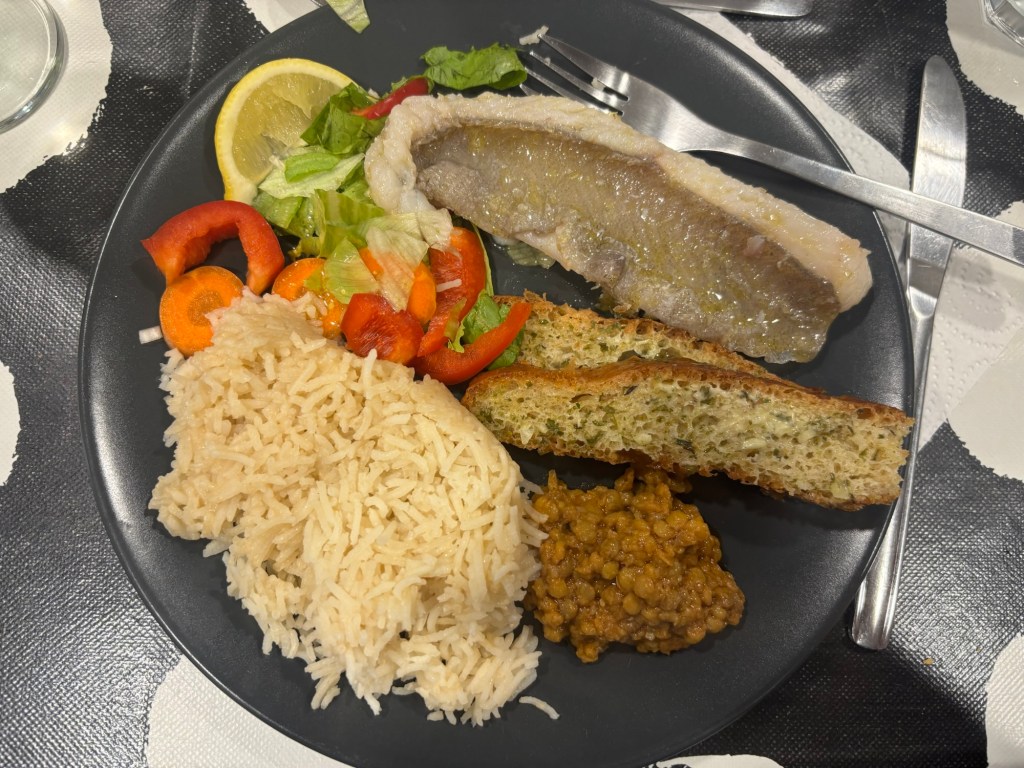

Well, first of all, dinner last night was phenomenal. Heidi, one of our hospitaleros, cooked up an absolute smorgasbord supper, and still under the banner of donativo. I hope the other pilgrims also tipped generously, because it must be really hard to whip up a spread like this without the generous donations of the pilgrims themselves. Remember, donativo doesn’t mean free – pay what you can, and what you feel the place deserves!

I was one of the last to leave this morning, as I was hoping I might score a few more stamps in churches along the way. as a matter of fact, they were all shut – every single one of them – so I needn’t have dawdled. I did only have 19km or so to go today, though, so I was in no hurry.

Leaving Canfranc behind, the Camino follows the river through the Valle de Aragón all morning, only turning away for the ascent to Jaca at the end of the road. What was only a mountain stream yesterday is already a powerfully flowing river, carving an impressive series of gorges in the granite along its course.

The next town along is Villanúa, where you are confronted with a strange sculpture in the shape of a many-limbed tree stump. On closer inspection, it’s actually an abstract representation of the women of Aragón who were persecuted for the crime of witchcraft during the Middle Ages. A single face carved into the structure drives the message home. There used to be a rope hanging from one of the branches, in a nod to one of the favoured methods of execution of witches, but it looks like that was removed.

During the Middle Ages, Aragón was knee-deep in tales of witchcraft. The Inquisition tasked itself with purging the region of heretics – a very broad umbrella that encompassed Protestants and “Judaizers” as well as witches – but such was the strength of belief in the occult in this remote and mountainous corner of Spain that witchcraft remained a talking point until as late as the 19th century, as can be seen in the pinturas negras of the Aragonese painter, Francisco de Goya.

The reason Villanúa comes into this can be found just off the Camino a hundred metres or so before entering the town. A series of steps cut into the rock lead up to a cave, accessible only via a guided tour. You can feel the chill of it as you climb towards it, and while there are plenty of perfectly reasonable scientific explanations for the drop in temperature near a cave mouth, it’s easy to see why such a place might have instilled a sense of fear in the ancients. The steps go deep, and in its heart is a large cavern lit by a great hole in the ceiling. It is believed that this was where the witches of Villanúa came to practice their akelarres – Witches’ Sabbaths – summoning evil spirits and bathing naked in the moonlight.

Of course, it’s just as likely that most (if not all) of those accused of witchcraft in the Middle Ages were completely innocent. Some local pedant seems to think so, anyway, adding a footnote to the information, claiming the accused were “too busy being burned and hanged by the misogynists of their time” (#romantizandomasacres).

It may well be true, even if it does take away from the mystery, but it’s worth bearing in mind that curanderos – folk healers – were frequently called upon throughout the Medieval period, especially in times of environmental stress. It’s plausible that some of the so-called witches really were trying to bring about some kind of change in their own way.

For me, it’s never been about their innocence. Whether or not they were witches is of no consequence (though I’d rather believe they were). The real demons of the story are the ones who were so strangled by their own fear that they saw fit to send these unfortunate souls to their deaths.

Either way, peregrino, if you feel a chill on your approach to Villanúa, it might just be the lingering malice of the Cueva de las Güixas on your left.

I had to double-back today, not because I’d forgotten something, but because I’d missed something rather special. The boulder-strewn fields before Villanúa harbour more than just witches’ grottos. There are older and more mystical relics by far, though I’d wager the average pilgrim completely passes them by, fatigued as they are from their three-hour climb down from the mountains.

It’s a dolmen – an ancient burial site from the Stone Age. There are quite a few of these in the area – large stones (or megaliths) being plentiful in the Pyrenean basin – but at least one can be visited from the Camino without too much effort. Dolmens like these can be found all over Europe, from the islands of the Mediterranean to northwestern France and Britain. In a way, they are just as much a symbol of the Camino as the yellow arrows, since they mark the westward expansion of our earliest ancestors as they moved west across Europe, until they could go no further.

The remaining fifteen kilometres or so to Jaca are easy to follow, if a little rocky underfoot. I’d spent so much time exploring the caves, dolmens and ruins of long-abandoned villages that I now had quite a long march beneath the risen sun, and my feet were definitely starting to complain after yesterday’s exertions. So, for once, I plugged in and listening to an audiobook – William Golding’s The Inheritors – as a way to push on. I hoped I might pop in on a few churches along the way, but as I suspected, they were all shut, so I got to Jaca by midday without further delay. Mariano, the musical madrileño from the albergue in Canfranc, had got there just before me, but we still had a little wait before the dueña showed up to let us in.

I bought lunch for myself and Mariano (I’ve had an easy ride with others treating me so far, and it’s only fair to share), before giving myself an hour or so to explore Jaca. The cathedral is austere but impressive, as Spanish churches often are, but its real treasures were in its Diocesan museum. At 3€ for pilgrims – with a stamp for the credencial thrown in – it’s a steal, especially when you see what it contains.

These Halls of Stories are bewitching beautiful, recreating scenes from the Bible for the illiterate masses while the holy words were kept in the jealously guarded secret language of the elite, Latin. I’m not normally one for religious art – the Renaissance obsession with ecstasy in its subjects is a major turn-off for me – but anything Gothic or earlier and I’m all in. The world was a darker and more mysterious place back then – and doesn’t that make it so much more interesting?

Latterly, I’ve become a lot more interested in ancient depictions of monsters, and the Devil definitely falls into that bracket. It took me a little while to realise the crowned imp in the image above – a detail from the mural of Bagüés – is a representation of Satan. I wonder what their reference was? With the red skin, narrow eyes and the feather-like crown, he almost looks like a Taino Indian, but that would be anachronistic in the extreme – these paintings were created four hundred years before Columbus sailed to the Americas.

Are there elements of Pan, the pagan god of the wilderness? It’s no secret that the goat-legged minor deity had a huge impact on the Christian devil, with the early Christian scholar Eusebius of Caesarea claiming the two were one and the same in the 4th century. Pan represented all that Christianity sought to suppress: vice, sin and animal instincts, crystallised in Pan’s half-beast limbs.

It’s not always goats, either. Traditional depictions of the devil often feature scaly or bird-like legs, akin to a chicken or a hawk. Most paintings of Saint Michael feature the Archangel standing triumphant over the body of a demon, and it’s easy to see the inspiration in these paintings: pigs’ ears for greed, scaly skin for the deception of the serpent, and thick, knotted talons for the eagle, one of the most feared and respected predators of the ancient world (if you’re not convinced, just look at how many world flags feature an eagle).

The references are much clearer here, but what of the Red Devil from the Bagüés mural? He has neither the goatee beard nor the cloven hooves. Who was the artist’s muse? Perhaps we’ll never know.

As I worked my way round the exhibit to the exit, a solitary face caught my attention. Or rather, a pair of eyes. Amid a wall of depictions of a saintly and contented Mary – Inmaculada, Asunción, Madre de Diós – a little painting of Dolorosa follows you with its eyes, which are bloodshot and full of tears. Her Son, arrested by the religious authorities and sentenced to death for the crime of working miracles, was crucified before a baying crowd.

Over a thousand years later, the same story played out again and again across Europe, only now it was done in Christ’s name. There must have been a thousand Marys who watched their sons and daughters befall a similar fate. And still it plays on.

Critics may say the Catholic Church puts far too much emphasis on the doom, gloom and damnation, but there is wisdom in the Catholic acknowledgement of the darkness. We might have been created in God’s image, but that does not make us perfect, and history tells us that some of us stray very far from the path when we try to be perfect.

Mary’s grief is eternal: it ripples across time.

Wow, that got pretty heavy. Check back in tomorrow for some more light-hearted adventures across Aragón! BB x