I’ll say this much for Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: it’s a beautifully reflective way to end the meseta experience, before you say farewell to the plains and reach the Órbigo floodplains at Mansilla de las Mulas. Sure, I ditched the other pilgrims to strike out upon that road, but it was totally worth it.

The hostalera in the donativo laid out a real spread for breakfast, so I helped myself to a better start than I’ve had in days: boiled eggs, yoghurt, pastries, flat peaches, cherries and a sandwich and a half for the road. Fuelled on such a feast, I was more than ready to tackle the Roman Camino.

After outstripping the other pilgrims, I had the rest of the Calzada Romana – the ancient Roman raid to the mines – all to myself. And what a morning for it! From the rise, you can see all the way to the distant peaks of the Picos de Europa, ringed with fire by the rising sun. The intermittent canals that cut across the causeway worked like mirrors, carving mercurial strips out of the earth, so that each one seemed to be a continuation of the sky above, and the fields around it a floating world. One of the best sunrises I’ve had on the Camino yet, and I’ve had a good one every day.

You get a good sense of the infinite on the Camino, walking in the footsteps of a thousand years of pilgrims who came before you (the earliest recorded pilgrimage to Santiago was in 930 A.D.), but walking on an old Roman road added another level of grandeur to the experience. The rough stone path made a change from a week of dirt tracks and concrete, and while it may well be wishful thinking in my part, it’s possible, however unlikely, that my feet touched the same stone that some long-forgotten legionary trod two thousand years ago. Nuts!

Sadly I didn’t bump into any ghostly centurions in the early hours of the morning, but the irrigation system provided a jump scare of it’s own: one of the mechanisms was so close to the path that I only had a five second window to clear the distance if I didn’t want to get soaked! That sure woke me up.

One huge plus of not taking the Bercianos route was the wildness of the calzada romana. I had my usual encounters with stonechats and wheatears (both northern and Iberian), but this unfrequented section of the Camino was a real gem for wildlife-watching. I saw my first quail whirring across the fields on tiny wings, and a couple of partridges, rabbits and a lone red deer rounded out this morning’s game. Every arroyo was alive with singing frogs – which is possibly how the nearby village of Burgo Ranero got its name – but a lonely nightingale had them beat toward the end of the road. A couple of ravens loitering around the ruined Villamarcos station chased off a buzzard that perched too close, then eyed me suspiciously as I walked on by. I found one of their feathers a little way on. It’s currently fastened to my walking pole for luck.

After several encounters with the grey males over the last few days, I finally saw a female Montagu’s harrier in the distance, and I must have clocked about nine or ten hoopoes by journey’s end. But best of all was a cuckoo that came out of nowhere during the morning’s only river crossing. Normally you hear these birds rather than see them, but this one was sitting in the middle of the road when a hoopoe gave it a merry chase for several minutes while I removed the grit from my sandals.

I got to Mansilla de las Mulas well ahead of schedule. I knew staying in Calzadilla would shorten today’s walk, but I still got to the albergue for 10.30am, meaning I had a good two and a half hours to kill before anything was open for business. All the same, this time it was as well that I did so: of the three albergues in Mansilla, one was fully booked and another, the municipal, was closed for renovations (and has been since April, at least), leaving me with no options but the pricier Jardín del Camino. I can’t complain after a very affordable night in a donativo, but when you’re used to paying 10€ as a standard, 16€ for a bed and a further 16€ for a menu peregrino is a bit steep… still! It’s all relative. Just think what that would cost back home….!

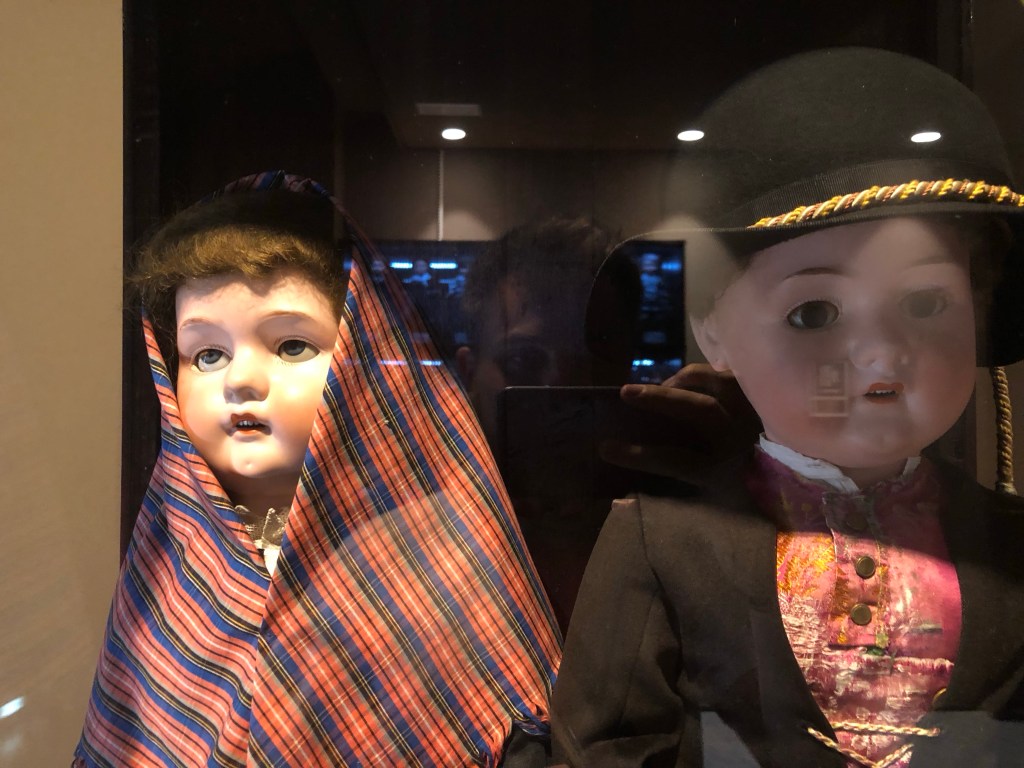

After a mid-afternoon snooze, I made a beeline for the Museo de los Pueblos Leoneses. Do check it out if you pass through – it’s a veritable gold mine of knowledge about the region and immaculately presented across three floors. I was especially interested in the local festivals and Maragatos, but the collection of dolls was equally memorable… though perhaps for all the wrong reasons!

I quizzed the lady at the desk about the signs and she laughed before I’d even finished the sentence. Apparently everybody asks the same question! Yes, she said, it’s not a random act of vandalism but rather the action of a movement which has deep roots in the region, thanks to the fiercely strong regional identity of the Leonese people. Given the chance, many would rather not be conflated with their neighbours. That much is clear from their local customs, costumes and festivals, which differ considerably from the Castilians. I’ve seen vaguely similar outfits in northern Extremadura (which was part of the kingdom of León at the zenith of its power) but the colourful guirrio is almost Latin American in its manic display. I was reminded of an Apache festival I saw in a book once. It’s funny how some people come up with the same concept despite a distance of many thousands of miles.

Tomorrow, I shoot for León. It’s not an overly long walk, or a particularly interesting one as it reaches the outlying industrial suburbs of the great city of the north, so I’ll tarry a little tomorrow and find some company on the road. I should probably also think about booking ahead for Santiago, since at the rate I’m going I really will be there in time for the festivities, and I hear they’re a spectacle that really oughtn’t to be missed if you can help it.

But until then, goodnight – everybody else has been in bed for a half hour already. Time to hit the hay! BB x