Plaza de la Merced, Málaga. 21.30.

I’ve arrived at the final destination of my journey: Málaga, ancient port city of the Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Moors and holiday hotspot of choice for thousands of guiris. It’s an odd place for a self-professed country boy like me to end the trip, but there’s a method to my madness: Spain’s foreign legion comes to town to accompany the Semana Santa processions on Thursday, which is a mighty spectacle, and what better a place to wind up my unofficial investigation into Spain’s mass tourism blight than in than the place where it all began, decades ago?

Doñana feels a long way from here. It’s quite easy to walk down a street in Málaga and hear no Spanish whatsoever. I set a timer and managed to clock a maximum of seventeen minutes before I heard a sentence in Spanish on my way to my accommodation: of the foreign languages in town, German was by far the most common, followed closely by Dutch and English.

The simple explanation might well have been that the locals had better things to do this afternoon than mosey about the high street: Holy Week begins in earnest today, and those Spaniards I did see were dressed in their Sunday best, or carrying musical instruments, white peaked caps or wire cones for the hoods of their capirotes.

Málaga, together with Sevilla and Jaén, draws in the largest number of spectators for its Holy Week processions: last year, the additional income from Semana Santa alone was an eye-watering 393 million euros in the space of a week. As it stands, around 80% of the city’s accommodation options are at full capacity. Some of that is down to the fact that Holy Week coincides with the school holidays in the UK, but a great many of those tourists will be Spaniards, for whom the processions are far more than just a spectacle.

For the average tourist (or even the irreligious Spaniard), Semana Santa can be something of a headache, both literally and logistically. The passage of the nazarenos and their enormous floats, numbering as many as six hundred penitents, can prove an unorthodox and lengthy roadblock, with the longest processions taking more than thirteen hours to conclude. You have to admire the zeal of the nazarenos for such a stakeout, especially those who do the whole thing blindfolded, barefoot or dragging chains, but it does have the effect of turning the streets of the old town into a live action render of the Snake game on the old Nokia phones: time it wrong and you can end up trapped between the undulating tail of two processions at once.

I couldn’t get anywhere near the Gitanos, one of the city’s most spectacular processions, as the crowd was five or six lines deep against the barriers, so I sought out the Estudiantes gathering outside the cathedral instead. Dressed in red and green, indicating their affiliation with Christ or the Virgin Mary respectively, the Estudiantes are the youngest of Málaga’s brotherhoods, drawing on the city’s youth for its members.

That much was plain from the behaviour of the nazarenos, who seemed a little less austere than I’m used to, popping up their hoods to drink from plastic bottles and waving at family members in the crowd. Perhaps it detracted from the magic, but then, my previous experience of Semana Santa is largely a small-town affair, where the sacred traditions of uniform anonymity are usually taken very seriously indeed. I’ve seen nazarenos scolded by their leaders for so much as looking into the crowd.

Málaga is notorious throughout Spanish history for its rebelliously liberal nature, so perhaps it’s unsurprising that their take on the Holy Week processions is a little more familiar.

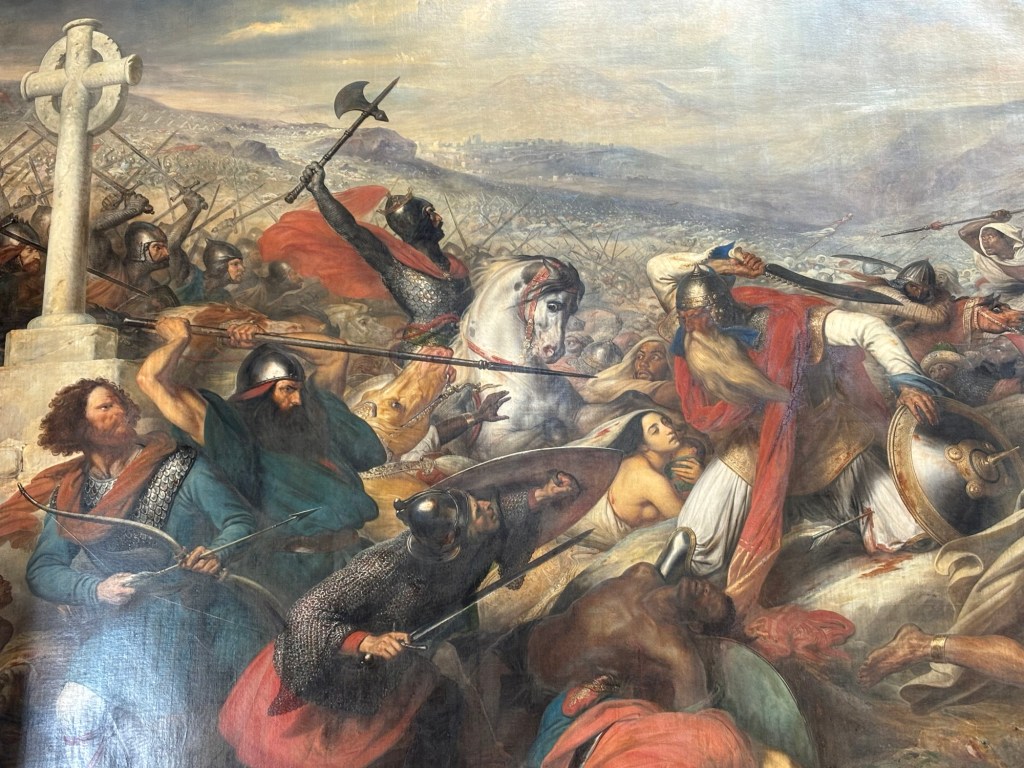

If I had a euro for every time I’ve had to explain away the comparison between the nazarenos and the villainous Ku Klux Klan – to students and Americans – I could probably afford another couple of nights of this holiday. The comparison seems far more obvious when the colour of their costume is white, of course – and I’ve seen unprepared American tourists jump out of their skin at the sight of the procession.

The simple answer is that Klan, among their myriad other crimes, purloined the outfit from here. The actual origins of the capirote are arguably darker still: they were originally known as sambenitos and were worn by the victims of the Spanish Inquisition, or rather, those victims granted the “mercy” of a quick death by strangulation for recanting their heretical ways and accepting Jesus. Those who didn’t were burned alive.

The different colours of the hermandades or brotherhoods may have originated in the designs on the sambenitos of the accused, indicating the crime they had committed or the fate for which they were destined. It’s believed that the Spanish started to make a connection between anonymity, penitence and overt professions of faith, and adopted the sambenito for use by those seeking to make penance during Holy Week as early as the 16th century. Certainly, by the middle of the 17th century, its use had become widespread, developing steadily into the tradition we now see today.

That makes the sambenito somewhere between two and three hundred years older than the robes of the Klan, who only officially adopted the ceremonial white robes under their reorganisation as the Second Klan in 1915.

So hopefully that puts the matter to bed.

I’ve never been troubled by their appearance, having encountered the nazarenos long before I learned about the KKK at school, but the procession isn’t without its issues for me. Something I’ve had to face here is my aversion to crowded spaces. It’s not agoraphobia, but it’s probably not far off.

In many ways, I feel more Spanish than English, but in one I am on the other side of a cultural gulf: I cannot stand the hustle of a crowd for the life of me. Spaniards seem to enjoy the hypersocial element of a giant conglomeration: there’s a thousand possible conversations to be had, a hundred new friends or connections to be made, and always the chance to enjoy something together – be that food, music, a joint or a spectacle. While an Englishman’s home is his castle, the Spaniard’s natural environment is in good company.

Good company is fine, but I have my limits, and it isn’t my idea of fun to be pushed, jostled and elbowed about by a massing crowd for the best part of a couple of hours. Semana Santa has always been a sombre, intimate affair in my previous encounters in Olvera, Villafranca and Villarrobledo. Here in Málaga, it is anything but.

The omnipresence of the police – all of them armoured and heavily armed – is a constant reminder of just how big the crowds are. They flank the processions, pushing the milling crowds back when they step out of line to take a selfie in front of the pasos (an affliction which, though it pains me to say, is very much a Spanish trend). One couple just kept trying, leaning into the paso as it passed so close that the costaleros – already carrying more than five thousand kilos on their shoulders – had to actively sway more to the right so as not to collide with them.

Crowds have a nasty habit of getting to me, as does selfishness, and it all got a bit much. Hemmed in by the processions, however, I had no choice but to either wait it out or duck into a restaurant until the way was clear. I chose the latter option.

I’ll have another shot at the processions tomorrow. I have gone from zero to sixty in the blink of an eye, coming from the total quiet and solitude of Doñana to… this. It will simply take a bit of getting used to, that’s all.

Until then, I have my books. Far too many of them. Thank goodness for extra bags on flights! BB x