Pizzería La Toscana, Santa Cruz de Tenerife. 19.55.

It’s raining here in Santa Cruz. There are quite a few guiris about – they’re the ones wearing shorts and popped-collar polo shirts despite the lowering grey skies – but they’re nowhere near as numerous as I thought they’d be. There are snatches of German, Dutch and Estuary English drifting from restaurants, but Spanish is by far the most common language spoken in the street. I find that encouraging, somehow.

Santa Cruz is a world away from the Elysian bliss of Chinyero. It’s a busy, 24/7 port town sandwiched between Tenerife North Airport and the tourist resorts of the south coast. Its harbour, one of the busiest in Spain, is a major stopover for cruise ships plying the Atlantic, just as it was for the early European voyages to the Americas, riding the Canary Current in a wide arc to the Caribbean. It’s one of the two capitals of the Canary Islands (the other being Las Palmas) and as such commands a sizeable proportion of the island’s population: nearly half, by some estimates. Like the greater part of Granada, the city began as a military camp, built by the Spanish in 1494 during their campaign against the Guanches / invasion of the island, depending on your sympathies.

It can seem like a characterless tourist metropolis at first, but there’s a lot to see once you start to scratch away at the surface.

The Plaza de España is a good place to start. In most Spanish cities, a square with the same name is usually right at the heart of the city. Here, it’s on the seafront. A guagua goes by, proudly displaying its green credentials (more than 70% of its fleet are hybrid vehicles). Opposite the bench where I’m sitting, a sanitation worker in a matching shade of green has eschewed conventional tools for a palm branch, a far more traditional (and renewable) method for street-sweeping. Alongside the usual plane trees – an effective biofilter used across Europe – a number of more exotic trees spring up out of the parks and gardens, including a few isolated dragon trees. Santa Cruz is wickedly green, as cities go: more than 80% of its municipal territory is a natural area, largely due to the Anaga Park which shoots up to the heavens from the city’s edge. In ecological terms, here is a city that is punching above its weight.

Next to the Plaza de España is an imposing sculpture, flanked by two silent watchmen: el Monumento a los Caídos, one of several Monuments to the Fallen that can be found across Spain. These sprung up under Franco’s dictatorship and many – including this one, if the stories are to be believed – were built using the forced labour of political prisoners. As such, there’s an ongoing campaign to have the monument altered to reflect the changing political landscape as Spaniards come to terms with the legacy of the dictatorship, nearly fifty years after Franco’s death.

It’s worth winding the clock back even further. What of the Guanches? Does this monument also honour those who gave their lives for Spain by taking these islands by the sword? I’m not one for presentism – it’s utterly absurd to judge the actions of those long dead by the quicksilver standards of contemporary ideologies – but I do think their story needs to be remembered.

One place that tells that story is Santa Cruz’s MUNA, the natural and archaeological museum. Don’t be put off by the reviews – it’s an incredible collection, but there are clearly a lot of half-arsed British tourists who visit and expect their monolingualism to be catered for, which is both arrogant and imbecilic. It’s also only 5€, which is a steal compared to some of the rates charged by similar museums in the UK… especially when you see what it contains.

The ground floor has an interesting feature on the formation of the islands, as well as some of its wildlife and how it came to be there. The first floor houses a collection of animals and insects (including a very large collection of butterflies) as well an array of archaeological finds from around the Canary Islands, from prehistory through to the time of the Romans and right up to the Spanish conquest in 1494.

There are a few mysteries still waiting to be solved that the museum nods to: were there once ostriches on the islands? What happened to the giant tortoises? Were the islands named after the seal colonies, or the large dog skulls found on the island? Did the giant lizards disappear, or did they simply shrink over time? And were the Canaries the inspiration for the Hesperides, the islands at the edge of the world where Heracles performed his penultimate labour?

Something more flesh (though perhaps less blood) than these mysteries can be found on the second floor, where the MUNA keeps its most precious artefacts of all: the mummies of the ancient Guanche people.

Before the Spanish came, the ancient Guanches of Tenerife had a custom not too dissimilar to the ancient Egyptians of mummifying their dead. Their origins along the Mediterranean coast of North Africa may go some way to explaining this practice, though it does not appear to have been a universal custom across the islands. Some of the mummies are in an incredibly well-preserved state, displaying most of their teeth and a full head of hair after nearly a thousand years. Wrapped in goatskin hides and concealed within caves and necropolises around the island, they have weathered the passage of time remarkably well.

Time, perhaps, but not the passage of man. Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt led to the discovery of many ancient Egyptian tombs and their treasure, which was one of the factors that started the 19th century archaeology boom. Guanche artefacts – including their mummified skeletons – were part of this mania. For hundreds of years before that, mummies found on the island had been dug up and carried off by enterprising scavengers. One tomb, Uchavo, was said to have contained nearly one hundred mummies when it was discovered. Mere days after the news broke out, the public broke in, taking with them – of all things – an enormous number of lower mandibles, which seem to have been the most valuable (and probably transportable) part of the mummies.

It’s for this reason that so many of the remaining skulls housed within the MUNA are missing their jaws. As to where these ended up, that’s anybody’s guess: doubtless they are now scattered far and wide, not just across the island but around the world.

Who were they? Such care was taken with some of the dead that they must have been menceys or kings of the Guanches. Mummification was a royal prerogative in ancient Egypt, so it stands to reason that the Guanches might have thought along the same lines.

While Tenerife has made some successful overtures for the return of its dead – with two returning from as far as Argentina – at least ten of the Guanche mummies are still held in collections around the world, with six in Paris, and one each in Madrid, Cambridge, Göttingen and Canada.

Nobody knows how many others may be out there, or in what state they may be in, but it is likely to be at least in the double figures. Sadly, most of those transferred to Germany were lost – along with many other relics of the ancient world, including the remains of the enigmatic spinosaurus – during the allied air raids in World War Two, which saw a number of museums razed to the ground. A Viking funeral, then, for a Guanche king or two – though perhaps not what their families had envisioned for their journey to the afterlife.

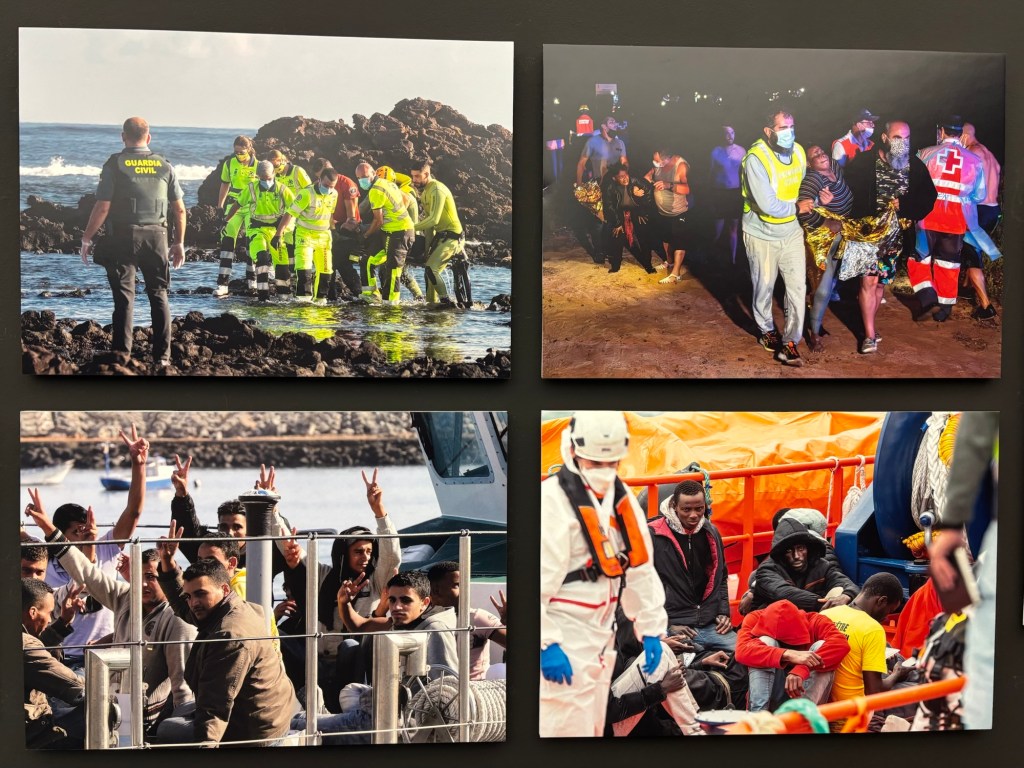

A fitting coda to the fate of the Guanches can be found in a temporary exhibit in the museum’s basement. Here, in a large and well-lit room, is a collection of a more modern tragedy: the African migration to the Canary Islands. Known as the ruta canaria, it is one of the most dangerous immigration routes in the world, since those making the trek in simple dugout canoes are at the whims of both the sun and the Canarian current which, if poorly timed, will carry the little boats out into the merciless wastes of the Atlantic Ocean. Most who make it that far will perish long before their boat washes up on the coast of the Americas.

This is, of course, how the first Canarians arrived in these islands many years ago, but with tighter security around the shorter but in some ways even more treacherous Mediterranean crossing, many African migrants continue to put their lives on the line to reach European soil – even if that soil is closer to Africa than any European territory. It’s also a growing concern: 2024 saw the largest number of migrants yet arriving on the shores of the Canary Islands at 46,843.

Behind each number is a harrowing personal journey, which is just as likely to end in misery or a body bag as it is in success. And even when they get here – what then? Do they find the Europeans any more welcoming than the countries they left behind them? What do they make of the hordes who descend upon these islands in the summer, riding in and out on cheap flights without a care in the world?

In one corner of the room there is a small exhibit, positioned almost exactly three floors below the Guanche mummies. It consists of an empty body bag on a rocky beach, scattered over with photographs like votive offerings. It’s a reminder that the dead who wash up on these shores, though faceless under black polyethylene veils, are not mere numbers, as the politicians would have you believe, but people whose journeys have come to an end. It’s our duty, if not our right, to make sure that their stories go on, so that their sacrifices are never forgotten.

The Guanches might be long gone, along with the giant rats and tortoises who came here before them, but the story of migration in these islands goes on. BB x