Calle de San Millán, Madrid. 21.03.

The gates of Hell are open night and day / smooth the descent, and easy the way.

Virgil, The Aeneid

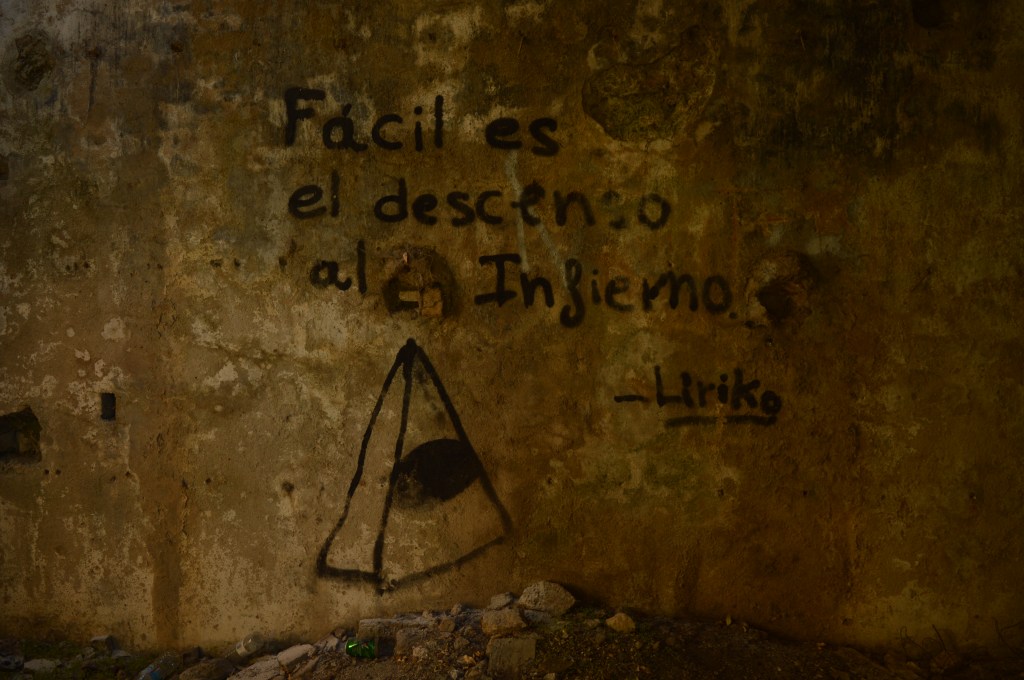

At the foot of the mighty bridge that spans the gorge over the Río Tajo in Ronda, the yellowing ruin of an old pumphouse steadily crumbles into oblivion. Trees grow out of its windows and human and animal detritus clusters against its walls, as though they shrink from the searching light of the world beyond. Abandoned spots like this would be covered in graffiti in England; profane scribbles and indecipherable tags whose meanings will fade from the world long before their makers. A single graffito marks the eastern wall. Of all things, it is a quote from Virgil.

The memory came into my head as I stood before Goya’s Pinturas negras in the depths of the Prado, bewitched – and not for the first time – by the unfettered darkness on the canvas.

In the opinion of this jaded wanderer, there are few artists who can hold a candle to Goya, an artist whose style was shaped – or, perhaps, perfected – by the ravages of one of the darkest periods in Spain’s history.

The Prado does a fantastic job at telling his story. On the top floor, illuminated by the brilliant natural glow of several skylights, his early works shine with an innocent halo. Paintings such as El quitasol and La vendimia tell of a happier time, when Goya was young and using his gifts to make a name for himself in the circles of the rich and powerful, as many an artist had done before him for generations.

Descend to the ground floor, and some of his younger naïveté is stripped away like a layer of paint to reveal a cunning eye for detail and social commentary. Unlike the illustrious royal portraits by Titian and Velázquez which grace the walls further down, Goya’s subjects are painted as they are, without any false veneers of lustre or glory. Maja vestida has a cute smile, but she is a pale imitation of Maja vestida, whose knowing expression betrays a far greater honesty.

And then you descend to the basement. The lights dim. War comes to Spain, Goya’s former patrons flee for their lives, and the country descends into chaos. Goya sees it all and sketches furiously. The illness that robbed him of his hearing pushes him into a deeper, darker school of thought, and his subjects trade their rosy cheeks and playful smiles for pallid masks and devilish grins. At the same time, the faces become much more recognisably Iberian, replacing the stateless Western mannequins who previously adorned his tapestries. Still a master of light, Goya now perfects its dexter side, drawing on the darkness of the maddening world around him, culminating in the macabre frescos of the Quinta del sordo. The sunken, bulging eyes of Saturn and his gaping maw stare out of the canvas with a malice that is at once pitiful and horrifying.

An American girl is toured swiftly around the room by her imperious mother, the latter commenting loudly on the broader collection ‘back home in Washington’. A Latin-looking schoolboy fills out a couple of questions on a worksheet on one of the paintings and moves on. Two young parents push their infant child by in a pushchair. They cast Saturn a brief glance and move on, a little faster. A gallery official in black and red watches from a corner, but nobody needs reminding that photos are not allowed in here. Goya’s demons still have the power to strike terror, two hundred years later.

Out in the daylight, Madrid goes about its business. My footsteps take me back into the heart of the city. There are a lot of indios about: current estimates hold that they make up one in seven of the capital’s population. In the city centre, I’d wager the ratio is even higher. Pizarro’s pigeons have come home to roost.

In a side-street, two officers of the municipal police search a couple of North African men, who have their hands on their heads – “Qué hacéis por aquí?”. A carton of box wine lies discarded in the road, ignored by a street sweeper who is watching the scene unfold over his shoulder, sweeping the same dust in circles.

In Plaza Santa Ana, a small group of Africans have laid out their wares on white blankets and try to flog what they can to passers by in reluctant, almost disinterested tones. Clutched in their hands at all times are the ropes fastened to each corner of the blanket, ready to be drawn up in a moment’s notice. These unfortunate hawkers are known in Spain as top manta, and are usually more in evidence in the larger cities along the coast: Barcelona, Valencia, Málaga… wherever careless tourist money can be found.

It crosses my mind, as it has before, to strike up a conversation with one of them. To get their side of things. To hear their story. Something checks me: a sense that unfriendly eyes are watching. I scan the square.

Sure enough, standing in the shade of a plane tree at the edge of the square is their overseer: a surly man in a Cameroonian football shirt. He appears motionless, but his eyes are fixed on the street vendors, who occasionally return his gaze, like nervous shorebirds before a sleeping crocodile.

My speculation becomes flesh when one of the hawkers approaches him with what seems to be a question. The conversation is obviously not an amicable one, and the overseer is on his feet and shouting, followed swiftly by his companion, a big chap with dark shades and a military-style beret. The overseer barks at the hawker and sends him packing. “No eres más que un puto negro.” It’s a loaded insult, but since it’s contained, hurled from one immigrant at another, nobody seems to notice. Madrid’s shoppers continue about their business. Tourists sink half pints of Mahou and Amstel mere yards away. A lost soul staggers to keep his balance, either too drunk or too drugged up to pay the scene any heed. The two Latino vagrants sleeping rough in the shade of a nearby bush hardly bat an eyelid. One stirs slightly, the other draws on his cigarette, casting a gentle orange glow in the shadows.

As I turn down a street toward the city centre, I see a police car slowly crawling toward the square. I turn around, but the top manta touts have already got wind of the impending threat: their bags are slung across their shoulders and they are retreating into the shadows. They will be gone long before the police arrive.

Goya’s Madrid is a dichotomy: a place full of light and consequently of shadows also, of rosy-cheeked beauty and ugly avarice. This is no less true now than it was two hundred years ago: it just wears Adidas trainers now.

Tomorrow I leave the capital behind and make for the windswept coast of Galicia. I have never been much enamoured of cities, being inclined to agree with the author M.M. Kaye, who described them as “the breeding places of the very worst aspects of humanity”. My destination is the Costa da Morte – the Coast of Death – the wrecking place of many a luckless merchant sailor. But its name is deceptive: for me, it is a place of unfiltered light and hope.

The gates of hell are open night and day / Smooth the descent, and easy is the way / But to return, and view the cheerful skies / In this the task and mighty labor lies.

Virgil, The Aeneid

The mighty labour has begun. There are still fragments of my heart in need of healing after last year’s American adventure. Hard work and endless endeavour have been a good palliative, but they are not the solution. Finisterre healed my heart before. It will do so again. I am sure of it. BB x