Pensión Matilde, Granada. 22.58.

Like most days where I crammed far too much into one day, this one is going to be difficult to write about. I’ve had writer’s block for the last few hours just trying to get started. So I’ll try to go over the highlights.

This morning began with a side of churros con chocolate at Café Bar Bib Rambla, an old haunt of my mother’s when she was on her travels around Spain back in 1988. It was just as good as she described it. Churros are definitely a once-a-year treat – I can’t quite justify any more than that – but Spain’s fondness for warm liquid chocolate is definitely something I share. I needed to kill some time (and break down some paper money into loose change) between the wash and dry cycles in the laundromat, so it was good to kick back and relax in a café that has stood the test of time.

After wrestling with the laundromat and coming away with a clean load of washing (yay!), I went back into the city in search of my Alhambra ticket. Along the way, I dropped in on the Cathedral, hoping to see Fernando and Isabel – and completely forgetting that they’re not interred within Granada’s cathedral at all, but in the Capilla Real next door. There’s a separate entry fee of 7€ for each, coming to 14€ if you want to do both. Of course, if you have the Alhambra card (which I also completely forgot I had bought) then both are covered. So I felt a little bit gulled.

Granada’s cathedral is… well, I’ve heard it said that it’s one of Spain’s most beautiful, but I’m not convinced. So many of them look the same, and while it may have its merits, it suffers from the same problem as the Cathedral of Córdoba: it’s sitting in the shadow of something truly unique and far superior in style. Santiago de Compostela boasts a spectacular cathedral, as do Salamanca, Barcelona and León, but Granada… I won’t get on my high horse about it, as my feelings are rather strong.

I popped into the Palacio de los Olvidados, mainly to check out an exhibition on the Inquisition (a long-term interest of mine) but also to investigate their collection of colourful art prints of Federico García Lorca, Spain’s greatest poet. I don’t know his works nearly as well as I should, so I’ve bought a couple for my classroom to inspire me – and the kids, of course. There’s a good possibility that he and my great-grandfather knew each other, as both belonged to poetic circles in the same part of the country and espoused left-wing ideals at the beginning of the 20th century – before the regime got to them both.

That alone should give me cause to dig a little deeper, but it’s the revelation that he was a musician – this has come far too late for a self-professed Hispanophile like me – that has really stuck with me. I must read his Poeta en Nueva York when I get home.

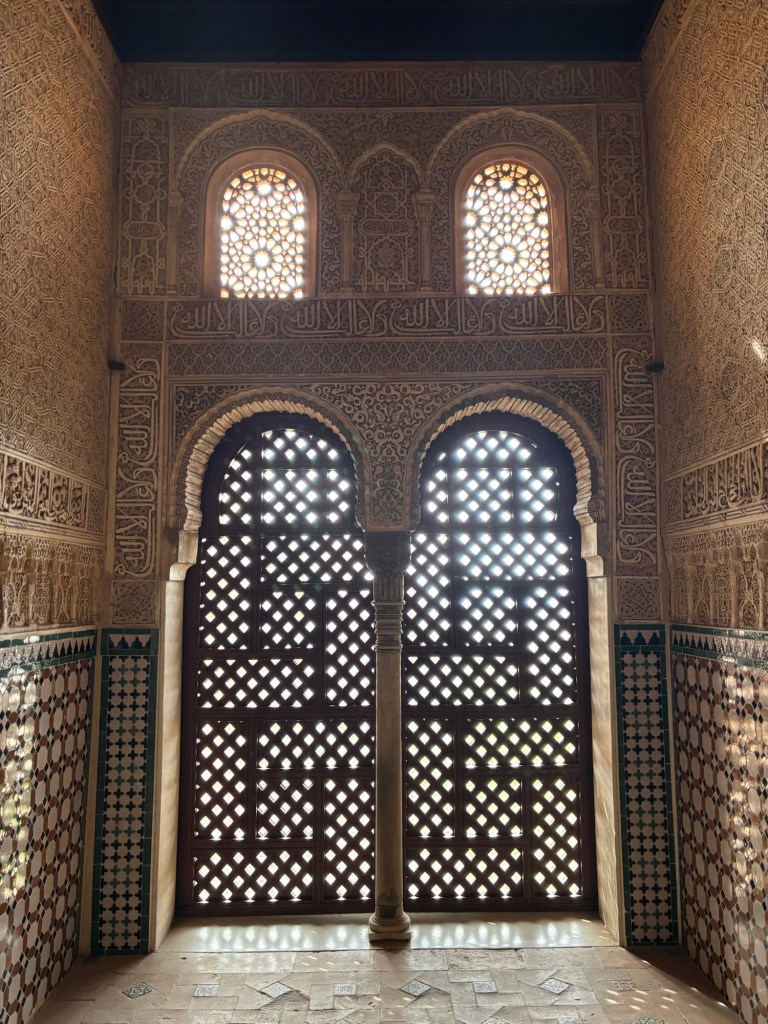

By the time I got up to the Alhambra, the brilliant blue skies of the morning had been concealed behind a glaring white haze. Thank goodness I got my winning Alhambra photos years ago, or I’d have been really quite miffed. No, this time, I relied upon my sketchbook. I spent almost half an hour in the Mexuar, the modern entryway to the Nasrid palace complex, sketching the stucco archway overhead.

A neat trick to carrying a sketchbook is that you can listen in on guided tours without looking like you’re obviously listening in. Another neat trick I have up my sleeve is that language is no barrier: in the half-hour that I spent in that spot (and another half-hour by the reflecting pool) I got the drop on an Italian tour, two Spanish tours, a French school group and their guide and a couple of English tours. I didn’t catch a word of the Polish tour, but six out of seven isn’t bad.

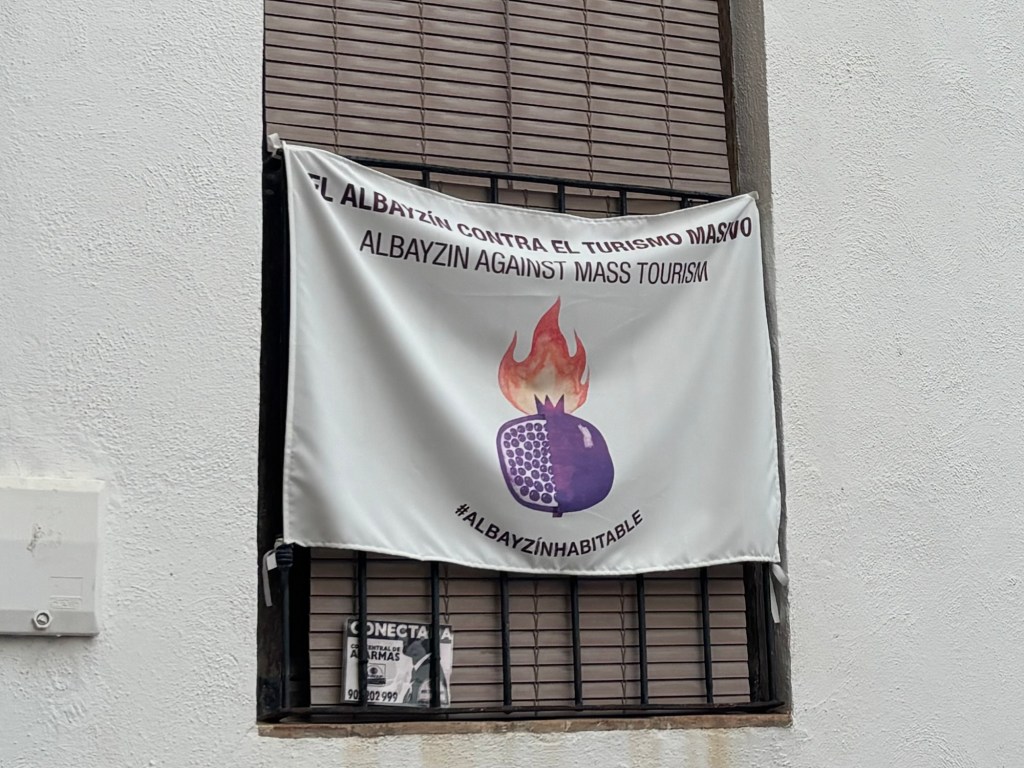

Did you know that the Alhambra receives – on average – around eight thousand visitors per day? That makes it not just one of Spain’s most popular tourist attractions, but an incredibly difficult job for the palace’s restoration team. Given proper care, floor tiles can last up to a hundred years until they need replacing. But let’s face it, your average tiled kitchen floor isn’t being manned by eight thousand new cooks every single day of the year.

In times gone by, men like Washington Irving had to step in to stop tourists from chipping tiles and plasterwork off the walls to take home. These days, it’s all the security guards can do to stop the school groups and Korean selfie seekers from leaning against the pillars and posing against the walls, rubbing away pieces of the past with every vanity shot.

Seriously – the number of peace-sign poses that some of the tourists were throwing… You’d think they were wandering around a Comic Con event rather than a medieval Islamic treasure.

Once, this place was even brighter. The faded beige stucco on the walls would have been covered in a rainbow array of colours, some of which can still be seen in the cracks in you look close enough. The lavish gold leaf and furnishings are, of course, long since gone, stolen by treasure hunters from the time of the Sultanate right up until the late 1800s. There were once carpets and drapes all over the place, too, but these were removed by the conquering Spanish as a fire hazard in an early concern for health and safety. I remember reading somewhere that they also had the floor lowered as the windows were too close to ground level, but don’t quote me on that. The Alhambra has been restored and modified so many times since its construction that it’s probably a far cry from what it originally looked like: a ship of Theseus or Washington’s axe, depending on which take on that metaphor you prefer.

I’ll tell you what was jolly nice, and that was seeing the Court of Lions. It was under heavy scaffolding when I last came here in 2011, so it was the only first-time experience I had on the tour. This enigmatic feature of the Alhambra really stands out, especially as depicting the physical form is usually proscribed in Islam. The fountain and its accompanying lions have long been a symbol of the Alhambra, though they were a late addition to the complex. It’s thought that they weren’t Islamic in origin at all but rather Jewish, as the fountain is believed to have come from the house of the Jewish poet Yusuf ibn Nagrela. The logic checks out: there are twelve lions in all, one for each of the tribes of Israel, and two bear the triangular insignia of the tribes of Judah and Levi on their heads.

It is, at least, an interesting theory.

My visit was cut short by the fact that I’d booked myself in for a tablao flamenco at the Palacio de Olvidados – yes, I caved in. And I am so very glad I did. I was worried that I’d find a lot of half-baked flamenco in town, but this was nothing short of spectacular.

There’s a depth to flamenco that just isn’t there in a lot of other folk music forms from around Europe: a heart-rending, wailing passion that can only be truly understood by the descendants of a people cast out and rejected everywhere they went. This is the soul of the gypsy on full display: naked, passionate and rebellious.

You could argue that the same case means white people can’t sing gospel music. I’d listen. Goodness knows I’ve had to table that argument before. But just because you don’t belong to a culture that produces a certain kind of music, that doesn’t mean it can’t move you.

I’ve no gypsy blood at all – as far as I know !but Flamenco moves me. It had always moved me. For whatever reason, Flamenco shoots straight to my heart and draws tears from my eyes. There’s a rawness to it, a gutsy, authenticity to its passion that is hard to find elsewhere. The voices of the singers tremble and fragment like a scream or a wail, and sometimes that’s exactly the point.

Don’t forget: the gypsies weren’t just ostracised, they were actively hunted as subhumans for years. Spain’s gitanos were the subject of hatred, scorn and outright violence since they arrived in the peninsula shortly before the fall of Granada. Being beyond the law, as it were, they were frequently targeted for enslavement, either in the mines or as galley slaves, which was essentially a death sentence in all but name.

In 1749, King Fernando VI organised the Gran Redada – the Great Gypsy Round-Up – with the express purpose of wiping out the country’s gypsies once and for all. Though not a genocide in the strictly modern sense, as the plan was to imprison rather than execute, the Redada’s stated aims of separating the male and female Roma and thus preventing them from “bringing about another generation” amount to the same thing.

And that’s just Spain. Holland and some German territories held heidenjachten (literally “human hunts”) until at least the 18th century, showing just how far the dehumanisation of the European gypsy could stretch.

Small wonder, then, that there is so much pain and anguish in the voice of the gitano. There’s centuries of agony to draw on.

Not to be dismissed is their footwork. Flamenco is as much a dance as it is a music form, and perhaps more so. There is no stately rhythm to follow, no pattern to predict: flamenco flows like water, where every drop runs its own course to the finish. Here, the dancers seem to lead the musicians. The eyes of the singers and the guitarist were on the dancers’ feet at all times, anticipating their every move.

I was enthralled. I adore flamenco. I love its maddening rhythms, its utter freedom, its unpredictability. Perhaps that’s the naturalist in me: it’s nature in musical form. I wouldn’t be the first to compare flamenco to a wild bird or beast and I won’t be the last.

Right – that’s quite enough for one day. Time to go and explore some book shops before they close. BB x