As Escaselas. 12.01pm.

Rain. It started early this morning, while I was still fast asleep, but it’s coming down quite hard now. The bus has just climbed the hill north of As Escaselas and is rolling towards Sardiñeiro, its windscreen wipers working overtime. Lichen-coated hórreos, a symbol of the Galician countryside, stand shoulder to shoulder with new-build white houses with wide garages. That strange mix of ancient and modern is ubiquitous along the pilgrim road: here is a wizened fisherman in blue overalls mending his lobster creels in the shelter of an awning, above which a sign advertises (in English only) “hippie/chill-out/goa fashion”. The lady on the bus behind me talks down the phone in a Galician accent so thick it could be Portuguese, while a couple of free-spirited Germans discuss their next steps. My German is rudimentary at best, but I catch the words “Mallorca”, “Sontag” and “yogi”.

Now and then I recognise a patch of road from that summer two years ago, when Simas and I pushed on together for the Cape, in warmer days when the wind blew west and America still seemed like a land full of hope. Now, the news is full of fury as Trump’s tariffs threaten a global trade war, and the US government tells its citizens to “trust in Trump”. Americans, it should be noted, have been notably absent from the pilgrim trail over the last few days.

Three pilgrims return home on foot in coats that cover their backpacks, and one pilgrim comes back the other way, striking out for the last stage of her journey. The Camino is eternal.

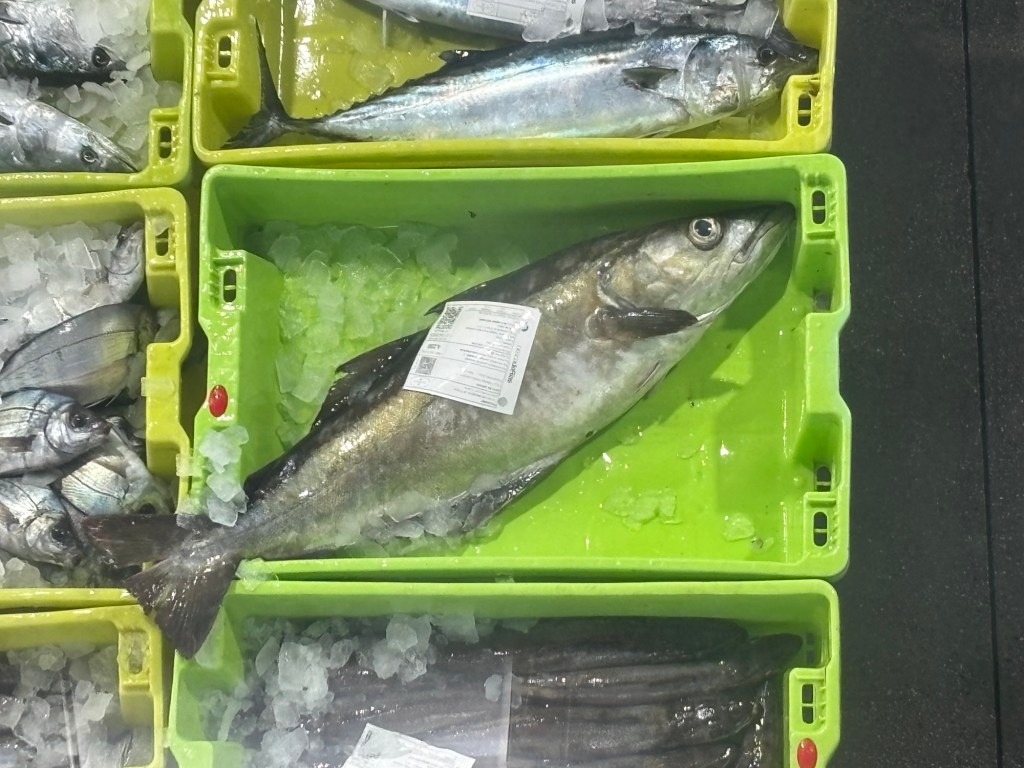

Spooky by Dusty Springfield plays over my earphones as the bus pulls into the former whaling town of Cee. A crude iron sculpture on the seafront is all that remains of that heritage, besides its name, though there are honorary clues all over the place: Restaurante As Balenas, a number of whale-themed hotels, a couple of whale-shaped hobby horses in the play park and even a friendly mural on a wall near the bus station, offering a whimsical nod to that monstrous practice.

Whaling has been outlawed here since 1986. Spain was slow to adopt the ban and Galicia was one of the regions hit hardest, though by that point most of the whales had long since been driven to local extinction. Lately, however, these majestic creatures have been sighted off the coast again, after an absence of nearly forty years, including the greatest of them all, the blue whale – the largest creature ever to grace this planet.

Perhaps they’ve been driven here by the depleting of their feeding grounds further south. Or perhaps – and this is what some scientists believe – it is an ancestral memory that has brought them home, in spite of the knowledge they must have of their kind’s slaughter at the hands of man. Something stronger than fear has called them back, the same compulsion that makes the tiny swallow travel around the half world twice a year. The same compulsion, perhaps, that leads pilgrims of all stripes to seek the end of the world here, as they had done long before the legend of Santiago washed up on these shores over a thousand years ago.

There’s a small bust-up in Muros, where the bus stops for a change of drivers. The two German pilgrims get off for a smoke and return with their rucksacks. The driver tells them they’ll have to leave their bags underneath if they’re headed for Santiago, as the bus will fill up when we reach Noia. One of the two – the one who speaks Spanish – argues the toss, asking if they can keep them at their feet. This annoys the driver, who points out that other passengers will need the seats more than their bags. Keeping my rucksack on me nearly got me out of a nasty scrape when I was backpacking around Morocco, but here in Spain, there’s no need to be quite so defensive. ALSA, Spain’s largest bus company, actually gives you the option to buy up the seat next to you, which seems a bit selfish. Monbus – a smaller corporate creature by far – is a lot more democratic.

There’s an enormous queue for the bus when it reaches Santiago, almost all of them under the age of thirty. It only dawns on me then that the only young people I saw out and about in Fisterra were pilgrims, and few of them under thirty at that. Spain is much like the rest of the world in that regard: its youth abandon the towns and villages for the bright lights of the city in pursuit of opportunities in work or love, returning home only to see friends and family, or once they have a family of their own.

My digs for the night are within a stone’s throw of the cathedral – quite literally. I can hear the bells chime every half hour from my room. I made a flying visit to some of the local bookstores, but wound up returning to my old haunt in Casa del libro in search of a couple of histories on Tartessos, a current fixation of mine. So far, my specialist areas include:

- Bandit legends and narratives

- Spain’s founding myths (esp. Pedro del Corral’s Crónica sarracina)

- El Cid & Frontier Epics

- Al-Andalus & Spain’s Islamic heritage

- Extremadura

- 17th Century Spain (Under Felipe IV)

- Gypsy culture and narratives

- Spanish wildlife (esp. concerning Doñana)

Once I’ve consumed these two new acquisitions, hopefully I can add Tartessos to that list!

I did make it to Mass this evening, but that’s worth a separate blog post, I think. So keep your eyes peeled! BB x