Dear José,

Many years ago you met my grandmother at a fair in London. Did you know what that meeting would set in motion? I guess not. You were young then – younger than me – and you were trying to find your place in a changing world. I often wonder what it would be like if you hadn’t lost your life so young. Would you have been a loving grandfather, or a distant one? From your letters, you seem proud, defiant, caring but also opportunistic, hell-bent on your dream to be a part of the future.

We never met, you and I, but you have always been with me. I tell your story wherever I go. It is what gives me the motivation to get up and work in the morning. It’s a sweeping love story, the one you had with my grandmother, complete with a tragic ending. Perhaps you might not have turned out to be the hero I have built you up to be had you survived. You would have been able to tell your own version of events, and the tale might have faded into the fabric of normality – and you could have lived a life like everyone else’s. But since you departed this world just days after my mother came into it, it falls to me to tell your story.

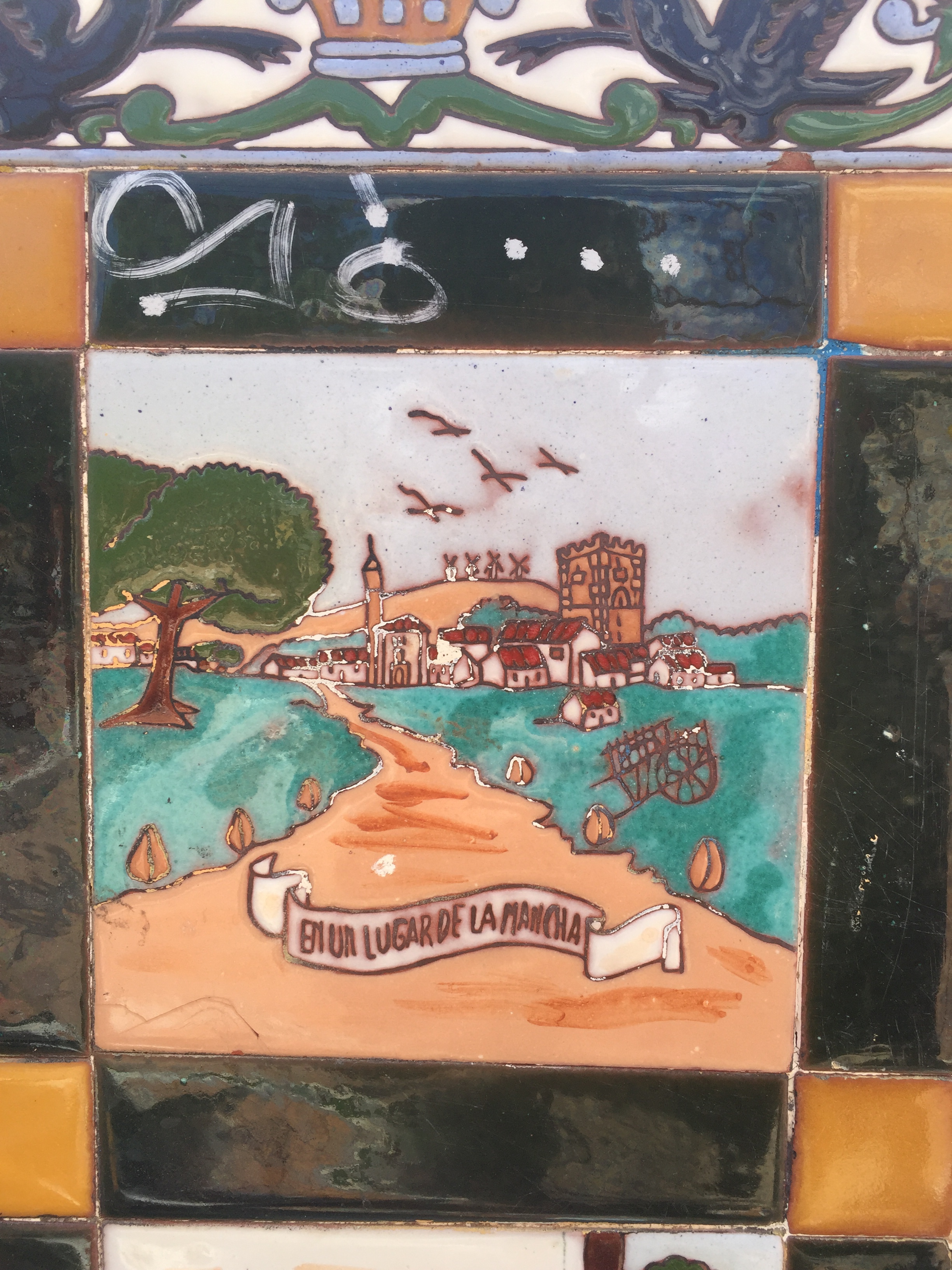

You were a natural linguist, José. By twenty-five you could speak Spanish, English, Catalan, French and German in an age when it wasn’t especially wise to command more than castellano, which makes you something of a rebel, too. That must have been your father’s Republican blood in your veins. The regime may have got to him, but his spirit lived on in you and your desire to see the world beyond your hometown. Perhaps it is only destiny that your tragic death would lead your daughter and grandson to spend the rest of their lives trying to find their way back to the place you tried to escape from.

I am English, and yet I still bookend that identity with the word “desafortunadamente” (unfortunately) when I’m travelling in your country. I have lived most of my life on this island, with the exception of three wonderful years in Spain – though none of them in the regions you called home. You grew up in the coastal plains of Alicante and plied your trade along the Costa Brava, traveling between Murcia and Barcelona in search of the future. Before I knew I was searching for you, I scoured the other half of the country: the jagged mountains of Andalusia and the wild steppe country of Extremadura. You came to London and fell in love with an English girl. I came to your country and fell in love – though not with a Spanish beauty, as I have so often hoped, but with the land itself.

As a boy, I was infatuated with her wilderness. I saw her marbled fields and the limestone scars of her sierras and I knew I had found a place like nowhere else on Earth. I saw the almond blossom in the snows of Grazalema and watched the midday sun dance off the shimmering surface of the Mediterranean. I saw the lights go out all across the countryside one night and saw my beloved Andalusia bathed in moonlight, as beautiful as a bride on her wedding night, and I started to understand why the Moors had wept when they were driven from this land all those years ago. I was just a boy, then, and I sought her beauty in living things that I could put a name to: chameleons, vultures, ibex and wild boar. But she was always there, waiting in the wilderness, weaving her spell upon me as I wandered about, camera in hand.

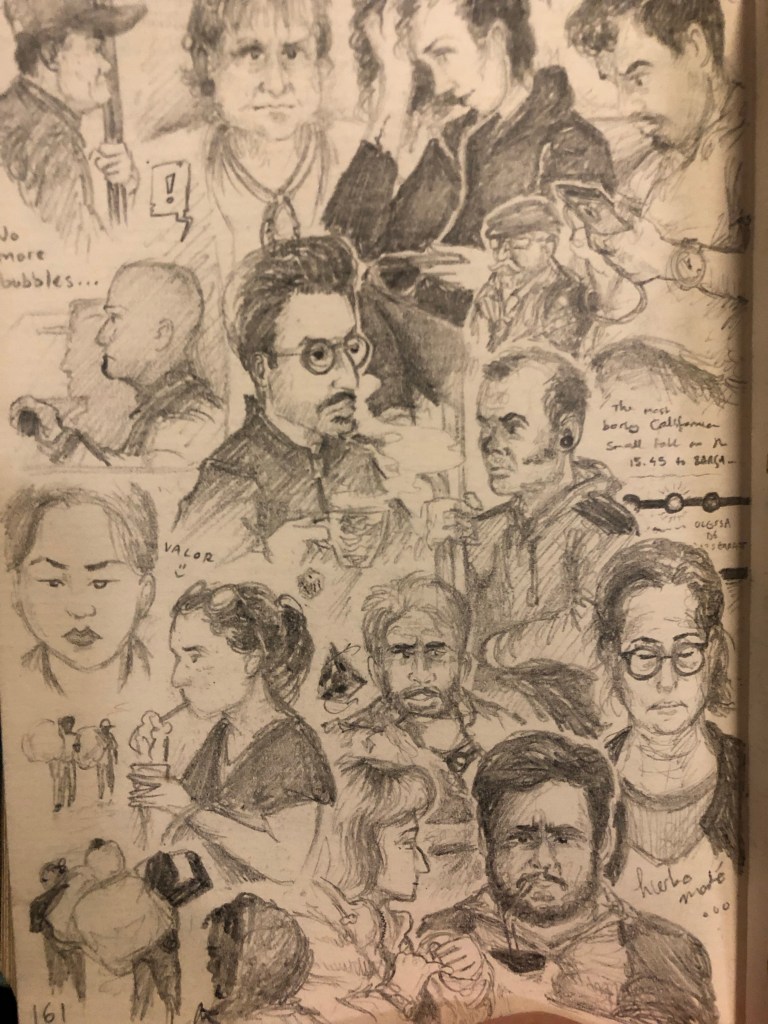

As a student, I started to perceive her with a keener eye. I looked beyond the wildlife guides and the history books and saw the people. In my own way, my infatuation turned into an awkward romance – quite literally, in one case. I learned the hard way that Spain guards its beauty jealously, and that, like any wild thing, she is deeply wary of the world beyond. You were brave, José, or at least restless – for you, I think, Spain was not enough. But for every one of you there must have been hundreds who knew that theirs was a beautiful country, and that change – if it must come at all – must be carefully and watchfully scrutinised as a stranger.

I was knocked about quite a bit as I came to terms with my identity. I wanted to be Spanish – I really, truly did – but it was more out of a selfish desire to be anything but English, rather than out of love and understanding. Every comment about my blue eyes, my accent and my figures of speech cut me like a knife. It was a reminder that the car that took your life also took away mine – my chance at being a part of a land and a people that I had grown to love, dashed upon the concrete by a stranger behind the wheel whose name I will never know.

I had almost given up on that hope until I found you. One day, the scales of that pretentious longing fell away and I remembered the reason I had set out on this journey, all those years ago – the journey laid out before my feet by my mother, who had far more cause to feel the pain of your loss than I. When I found your family, at last, everything suddenly came together. If I had any doubts, they were lost forever. I did have a family in Spain: cousins and uncles and aunts, as many as I could ever have hoped for and then some. And I found you, José, together with your mother Mercedes. Did you like the flowers I left for you? I am sorry I did not leave any there this year. I will make amends for that before the year is out. But know that you are always in my prayers. Every time the rosary is in my hands, or there is a prayer on my lips, there too is your name – for you have been my guiding light ever since.

You probably don’t want me to put you on such a pedestal. And I’m old enough now and wise enough to know that pedestals are usually set at the feet of false idols. But if it weren’t for you, my life would be half a life. If you hadn’t met my grandmother all those years ago, I might never have seen the things that I have seen. Sure, I might have lived a happier, more grounded life as a full-blooded Englishman. I might have taken a regular job – whatever that is – and been content to settle down with a girl from the city.

But your Spanish blood changed all of that. Mixed in with that steadfast appreciation for order and eccentricity in equal measure that is so English runs an unquiet vein that demands adventure and passion – something greater than the ordinary, something beyond. I have railed against it and wished for stability and the loving arms of a girl who will ground me, but again and again I feel it, the call of the homeland, the maddening restlessness that drives the swallow south every autumn. I have gambled my life upon that restlessness, trading friends and normalcy for that fleeting dream that is always just beyond my reach. I am still here on this rock, teaching your language and culture and spreading your love of music wherever I can, but always I hear the call. It is fierce, elemental, like the thunderclouds of spring or the waves of the Atlantic.

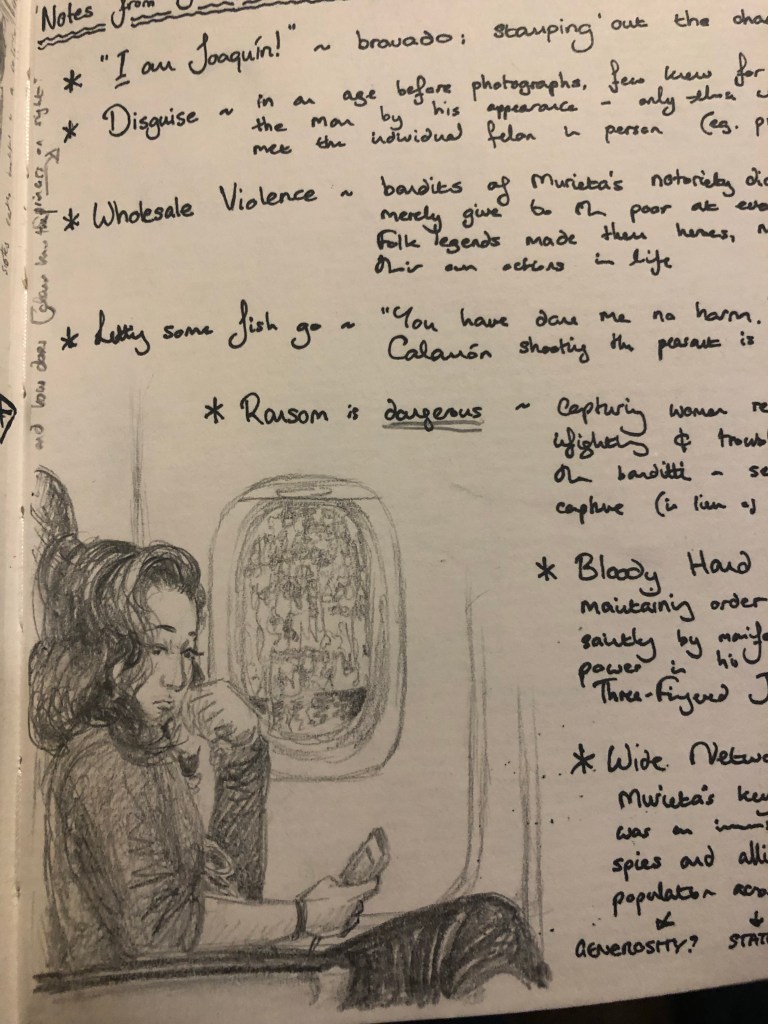

I do not know where I belong. I don’t think I ever have, and that’s why I’ve always drifted, loving and cherishing friends deeply while they were near, and then letting them slip through my fingers as the current carried me on. The stability I long for and the restlessness in my heart make for strange bedfellows – they are more like ships in the night. I have no home beyond my work, and my work is my anchor. You were no teacher, José, but we are kindred spirits, you and I: languages are my trade just as much as they were once yours, and while you used yours to build a bridge to England, it fell apart when you died, and I have spent the rest of my life building another one, both for me and for all of the children in my charge. Not all of them will follow me across that bridge, but if I can share with those few that do just a fragment of that brilliant light that waits on the other side, I will have done something to honour your legacy.

Watch over me, dear José. Give me the courage to chase my dream over the horizon, wherever it may lead.

Watch over me, dear Mercedes. Give me the wisdom and the words to tell my stories, and I will carry you with me everywhere in my journal just as you once did.

Watch over me, dear Mateo. Give me the power to face my fears head-on, the way you did when the government forced you out of your job. You found love in the middle of a war and dreamed of building a library. Perhaps that’s why they came for you. I am at least halfway to realising your second dream. Guide me toward the light of realising your first, also.

I don’t know what your take was on faith, José. From your letters, I don’t imagine you had an awful lot of time for it. But I do.

So watch over me, Blanca Paloma. You were with me when I was just a boy and you showed me that Paradise had a name. You walked with me on the Camino along with the spirits of my ancestors. You introduced me to the hoopoe, the kite, the ibis and the lynx. And you healed my heart when nothing else could. I know you are with me – I feel it in my heart.

I do not know if I am on the path you intended for me, José, but I know that it is the right path. And someday, I will close the circle. I will finish what you started.

Your grandson – linguist, adventurer, romantic and man after your own heart. BB x