Albergue de Peregrinos de Nájera. 12.59.

I was supposed to take the day off today, but as it’s a Sunday, nothing is open. No shops, no museums, zilch. So, since my intention to use my rest day to restock was somewhat redundant, I set out at the relatively tardy hour of half past six for Nájera.

Logroño must have been partying late into the night, like Jaca last week. There were more than a few amorous couples locked in each other’s arms in front of doorways on the streets running off the Gran Vía. The average age a Spaniard is able to leave home is now in the mid-thirties, which must make dating considerably more complicated here: the sexual revolution has happened, society has caught up, but the financial reality has got Spain’s youth in a stranglehold.

There are still Palestinian flags everywhere you go. It probably chimes with the mindset of the average liberal peregrino, but there’s another reason they’re so ubiquitous in this stretch of the Camino: we’re still in the Basque territories. And if any people are more likely to sympathise with an oppressed nation under the heel of a supposed colonising force, it’s the Basques, whose own freedom-fighting/terrorist organisation, ETA, only stopped its violent methods in the 1990s. I’ve seen one prayer in Hebrew for one of the captives still held by Hamas along the Camino, so it’s not entirely one-sided, but the Palestinian flag is far and away the most common flag along the entire Camino so far.

I reached the Parque de la Grajera about an hour after leaving the city. I was early enough to catch the night herons that seem to hang around the place. They have a somewhat patchy distribution across Europe, but they were here when I last did the Camino from Logroño to Burgos in the spring of 2023, so I was glad to see them again.

They were much too far off for a photograph, but the park’s red squirrels were a lot more obliging. Without the invading greys to worry about, they seem a lot more confident around people here, and so I was able to get quite close – or rather, it came quite close to me on its jaunty sortie across the bridge.

Today’s route featured a small pilgrimage of its own, to the shrine of La Virgen del Rocío. She is, in the humble opinion of this devotee, one of Spain’s most beautiful incarnations of the Virgin Mary. She certainly knows how to pick out a home, with her sanctuary within the Elysian marshes of Doñana National Park far to the south… and here she is, watching over a lagoon in La Rioja.

I remain convinced that it was partly her intercession – and that of the natural paradise where she resides – that healed me at last from last summer’s heartbreak, and it is partly because of that intercession that I am walking the Camino this summer… to say thanks. I owe her that much.

There were more squirrels to keep me company around the edge of the lagoon, including a boisterous couple that were quite unfazed by my presence, chasing each other up and down the trees on the edge of the lake. You have to travel quite some way in the UK to see these endangered creatures, since the American greys drove them out, but here they’re much more common.

La Virgen del Rocío is, among her other titles, a water spirit of sorts. Maybe that’s why she speaks to me more than the other incarnations across Spain that I’ve encountered: El Pilar, Remedios, Guadalupe… I’ve always felt some sort of connection to marshes and wetlands. It may seem odd that Mary, a woman from the hill country of Southern Galilee, should have such a devoted following in the wetlands of southwest Andalusia, but there it is.

El Rocío is the Spanish word for dew, and the Marian association with the Morning Star – Venus – as the herald of the rising sun is almost as old as her worship as the Mother of God.

I’ve often wondered whether the various Marian cults across the Mediterranean aren’t simply evolutions of the Roman tradition of the lares – guardian deities assigned to individual places – or perhaps even the Celtic peoples before that. In that light, it’s easy to see why other Christians find certain aspects of Catholicism hard to understand. But I think we’re all reaching for the same thing. Many Protestants would say they’re reaching for a more personal relationship with Jesus.

Well, what could be more personal than feeling an intense connection to God through a place that is so close to your heart?

West of Navarrete, the Camino meanders through a vast network of vineyards: a reminder that the tiny autonomous community of La Rioja punches above its weight in wine production (even if it can’t meet the demand on its own). It’s a 29km walk from Logroño to Nájera, but an easy one, and I was in town shortly after 12pm from a 6.30am start. I call that good going.

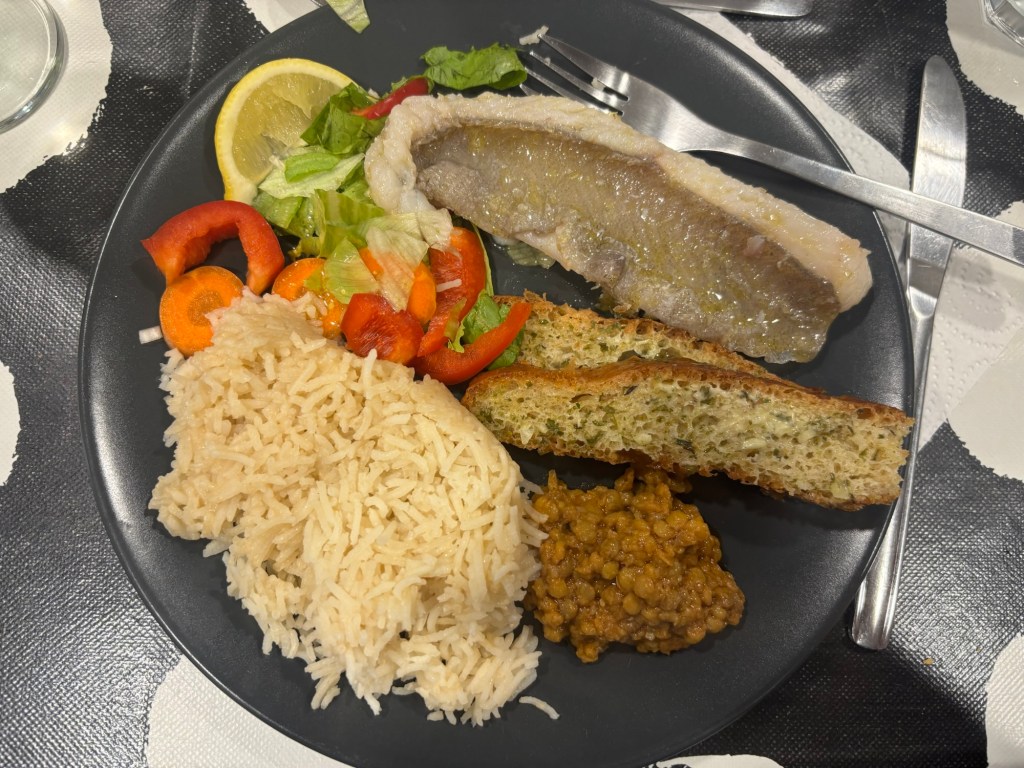

Reunited with the young folks tonight after an Irish exit and a hiatus of two days. Time for a sociable pizza night! I think I’ve earned it. BB x