Hotel Rambla Emérita, Mérida. 20.16.

It’s been raining all day again. I was out late with Tasha last night catching up on old times – neither of us could really believe that it’s been nearly eight years since I left – so I didn’t begrudge the downpour for a long and cosy morning in bed. You don’t have to be busy every day of the holidays, even when you’re abroad.

Luckily, I was all over Mérida yesterday with my conjunto histórico ticket, granting access to all the city’s Roman ruins, so the only thing I missed out on was the Alcazaba, which I might visit tomorrow with Tasha and her boyfriend Antonio, if he’s up and about. I don’t think I’ve seen the Alcazaba before – one tends to focus on Mérida’s Roman history rather than its Moorish past, and there are older and more impressive alcazabas (the Spanish rendering of the Arabic qasbah) in Andalucía: Sevilla, Córdoba and Granada, to name just the obvious ones.

Mérida isn’t unique in having a Roman amphitheatre either. There’s a pretty spectacular one (albeit less often seen) in Santiponce that I’ve often seen from the bus on the way in from the north. But there are a few more unique treasures to be found in Extremadura’s administrative capital, and I thought I’d tell you about one such gem below.

Let’s start with the lady of Mérida – because every Spanish city has its special lady. This one is Santa Eulalia.

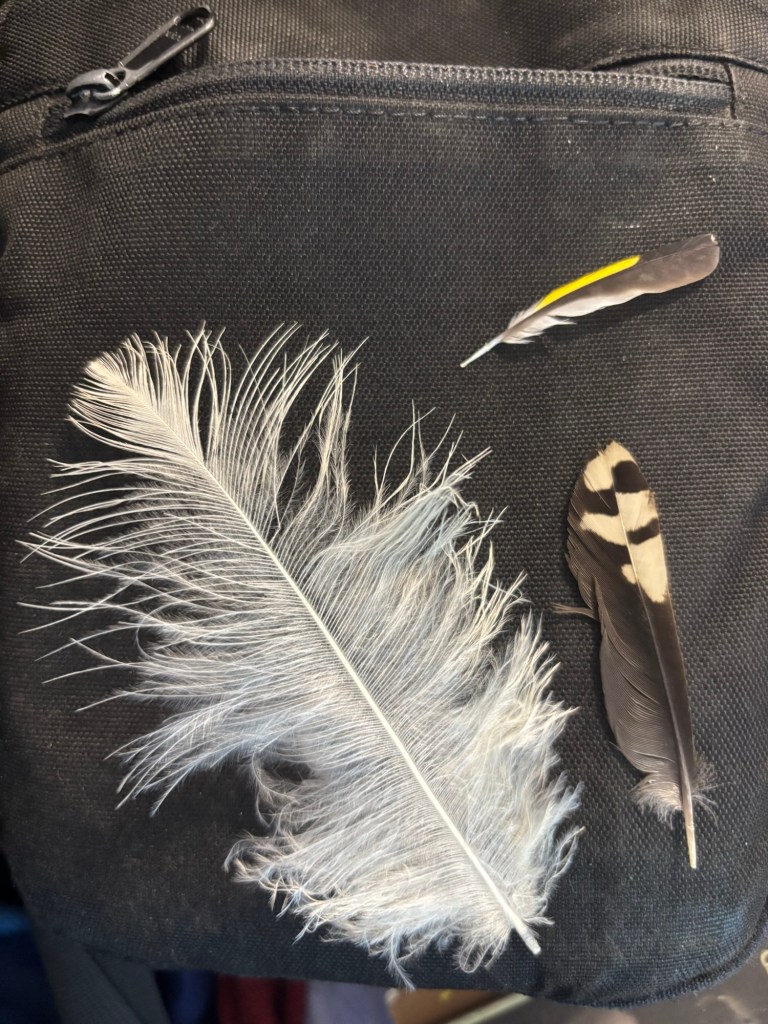

Eulalia of Mérida stands tall above the other Christian saints of Spain, which is especially impressive as she only lived to around twelve years of age. A Roman Christian, she and her family were forbidden to worship God under the Persecution of Diocletian. Incensed, and unable to keep her faith to herself, Eulalia fled out of exile to the city of Emerita Augusta, where she openly challenged the local governor, Dacian, insulting the pagan gods whom she was commanded to worship. After a few desperate attempts to reason with her, Dacian had the girl beaten, tortured and burnt at the stake. According to legend, Eulalia is said to have mocked her tormentors until her dying breath, which came out in the form of a dove.

Eulalia was once a great deal more powerful than she is today. Before the rise of the cult of Santiago, it was Santa Eulalia de Mérida in whom the Christian soldiers placed their trust as they made war on the Muslims occupying the lands their ancestors had once held; and it was to her tomb in Mérida that thousands of pilgrims travelled during the Middle Ages, before Santiago Matamoros muscled her out of the picture.

At least one of my Protestant Christian friends has remarked at some point about the thin line between the Catholic Church’s veneration of saints and idol worship. Surely – they have reminded me – it is God and by proxy his son, Jesus Christ, to whom prayers should be made, not the pantheon of mortals who claim to be able to intercede on my behalf?

I can see the argument as plain as day. There are shops up and down this country selling nothing but saint souvenirs: votive candles, icons and fridge magnets, scented rosaries and car ornaments. I have a few myself – a family rosary from Villarrobledo and a more personal one from La Virgen del Rocío, which these days is on my person more often than not.

However, I don’t think it’s as simple as that. How frightfully urbane, to assume that the only true relationship with God is a detached and decidedly modern Western take on prayer. How tremendously big of us to assume that we can comprehend a force that it is, by its eternal nature, beyond our understanding. Community is a powerful agent – it seems only right that the spiritual world, Christian or no, has a network of pomps to streamline the neural network that binds us all together. On Earth as it is in Heaven, as they say.

Spain has a long history of wandering saints. Santiago journeyed beyond death to Galicia, sparking the most famous pilgrimage in Christendom. Guadalupe travelled from her mountain home to México to become one the most venerated Marian cults in the world. Eulalia was dug up and reinterred in Oviedo, where she became a figurehead of the Reconquista (I genuinely had no idea I was standing before her final resting place this summer). Teresa of Ávila’s body parts have travelled all over, most famously her Incorruptible Hand, which used to grace Francisco Franco’s desk.

Tomorrow, I make for Sevilla. Journey’s coming to an end. I’d better make sure I’m fully packed. BB x