One of the very best things about my job is my role as the middle school Gifted and Talented Co-Ordinator. As one of the few not on the G&T list in my grammar school days you might jump to the conclusion that there’s a chip on my shoulder there, but that’s not quite right. A more likely excuse is that in my sixth form days I was involved with my school’s Arts and Humanities Society, a pre-university lecture/seminar group run by my history teachers, and it was so pivotal in my development as an academic that I have spent the last few years wanting to set up a society of my own here. The simple fact of the matter is that, four years into my teaching career, I’ve found the niche that allows me to do what I’ve always wanted to do: explore learning for its own sake.

So far, what that has entailed is two after school lectures, one every half term, on subjects that my students might otherwise not encounter in the classroom. I got the ball rolling last term with a talk on the Aztec, where we went on a whirlwind tour of the history of the Mexica, the geography of Mexico and the fierce deities of the Aztec pantheon – as well as the tale of Cortes, la Malinche and the fall of Tenochtitlan. Since I’d much rather the sessions were seminars rather than dialogues, I make a real point of taking questions and posing some of my own as I go so that these talks are more of a journey together than a lesson with me at the front. In the best of all possible worlds – the world I’m trying to create in a Monday afternoon classroom – I’d like to come out of the hour knowing that I haven’t added to their knowledge so much as given them new avenues to explore. That’s why I conclude each session by asking my students what they’d be interested in learning about next time. Today, there were a lot of requests for Chinese history: the Tang Dynasty, the Civil War and the Opium Wars. Perhaps that’s because we took a ride with Zheng He and his treasure fleet this afternoon.

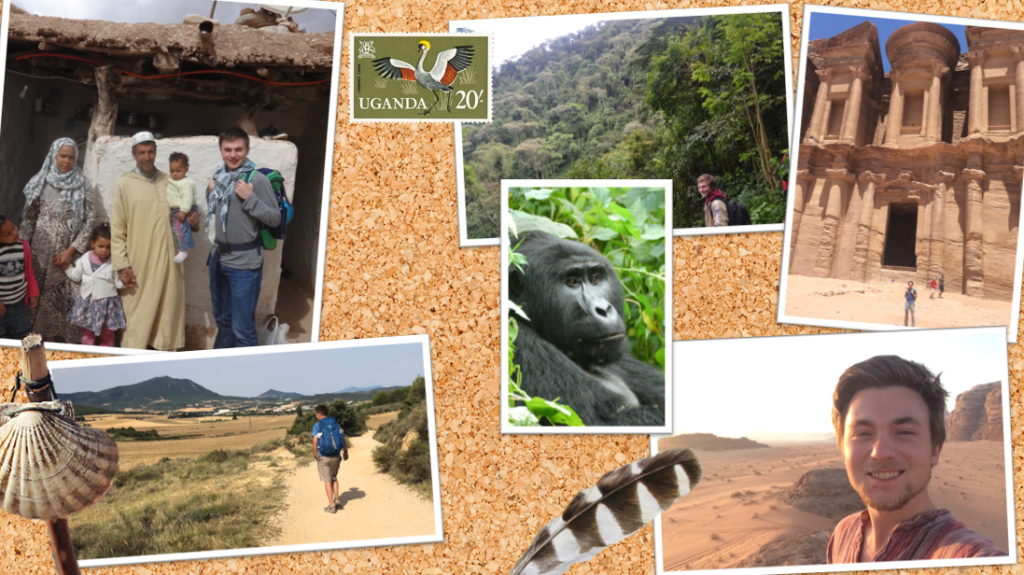

Today’s talk was on Explorers, after one of my students requested a lecture on adventurers like Cook and Lewis & Clark. It was so much fun to research, not least of all because I have been lucky enough to do no small amount of exploring myself in my twenty-eight years on this Earth. I started off with the graphic below and, after we’d agreed Mr Young really doesn’t suit a beard, I picked my students’ brains about the locations in each one. Using the clues of this man’s local dress, and the mountain gorilla, and the facade of the rose city, and the scallop shell, they smashed every single one. Proud teacher moment.

I get a lot of satisfaction from seeing my kids go from strength to strength in the language classroom. But I’d call myself a seeker of knowledge for its own sake long before I call myself a linguist, and this is where somebody like me is in his element. Seeing the electric enthusiasm of my students sparkling like Saint Elmo’s fire from their outstretched fingers as they vie to share their collected wisdom with their peers, answering questions I haven’t yet posed four slides in advance because they read this book here or their parents showed them that thing there… There’s few things like it. It’s one of those “this is why I teach” moments, and the best thing about it is that you’re not having to do an awful lot of teaching. The knowledge is there. All you have to do is open a few doors.

This afternoon, over the space of an hour, we traveled the world. We sailed around China, Africa and the Indian ocean with Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta and Zheng He. We crossed the Atlantic with Leif Eriksson and the Basques and wondered what took Christopher Columbus so long. We learned to navigate by the stars and explored the constellations. We met mild-mannered mountain men, meddling missionaries and bloodthirsty bandeirantes. We searched for Amelia Earhart’s final resting place, climbed the Matterhorn (and fell down the other side) and, saving the best until last, we sat down and had a difficult conversation with that most impressive of adventurers, and one of the greatest linguists (or even, in the opinion of this author, Britons) of all time: Sir Richard Francis Burton. Somehow I managed to cram it all into the space of an hour.

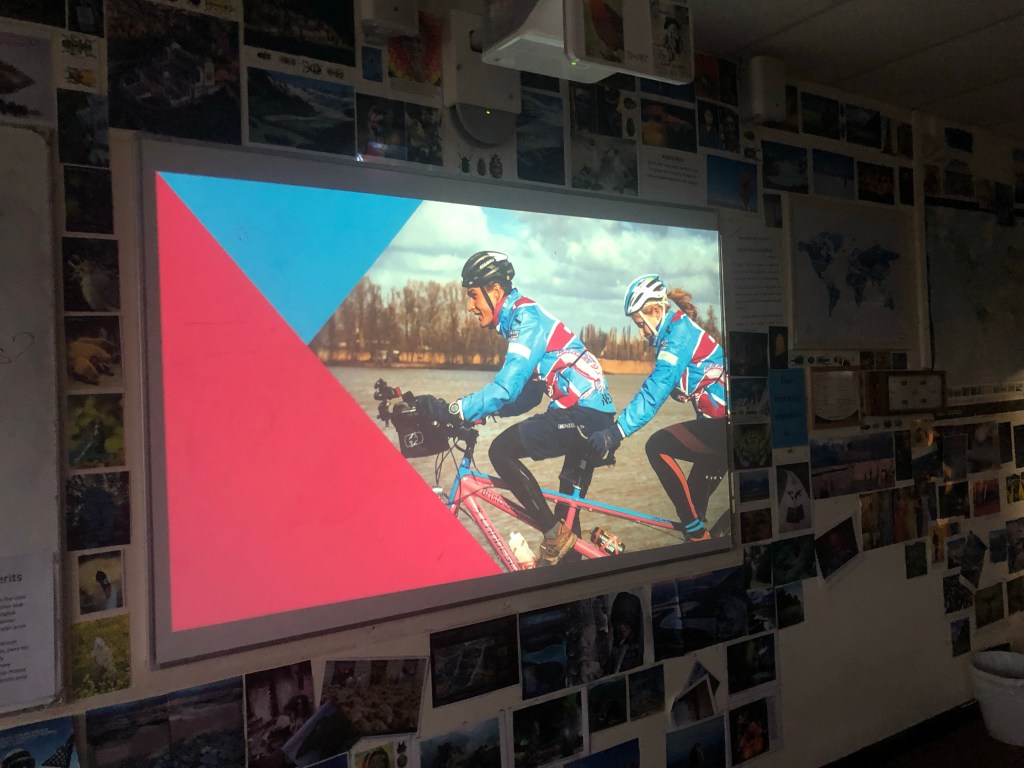

Well. Almost. We ran overtime by about five minutes, but not a single one of my kids reached for their phone, or started to pack up and leave. And that may well have to do with the fact that I chose to end the talk with the personal story of a friend of mine who gives us all a reason to believe in hope again: Luke Grenfell-Shaw, triathlete, fellow Arabist and CanLiver, and champion of the Bristol2Beijing tandem ride across the world. The best thing about that? Once again, I wasn’t even adding to their knowledge. Two of my students lit up at the image alone. They knew this man. They had heard of him.

I can’t tell his story. I won’t. Read about him for yourself – there are few men in this world like Luke. And though I poured my heart and soul into this evening’s talk, I’d like to think that it will be Luke’s story that my kids take home tonight. The world is vast, and explorers and adventurers have already been over so much of it and documented everything. But that doesn’t mean the age of adventure is over. People like Luke are living proof that adventure lies within, in our hearts and in what we choose to do with the world around us.

Godspeed, Luke. We’re rooting for you here.

https://www.bristol2beijing.org/

In the meantime, I’d better find myself an expert on Chinese history! BB x