Winter is on the retreat. It began on Tuesday, when I heard a dunnock singing from the top of one of the trees by the church. A tiny foot soldier, the herald of the advance guard that has set up camp at the edge of the Weald, singing his heart out in defiance of the lingering cold. The dawn chorus grows in strength by the day. It woke me before my alarm did yesterday. There are still a few redwings about, but it’s been a long time now since I heard the cackle of a fieldfare, and the evenings are getting lighter. Spring is still a little way off, but it is finally on its way.

I’ve been a lot more mobile these last few months. No, it’s not because I finally have a set of wheels – I don’t, and that is still very much a work in progress – but all the same, it has meant I have spent even more time in the Weald than ever before. While my head and my heart have been busy elsewhere, my eyes and ears have not taken a day off. The shifting seasons and the changes they bring have always been a major source of happiness for me, and there have been so many things to see on my weekly commutes that I’ve been pretty spoilt for choice.

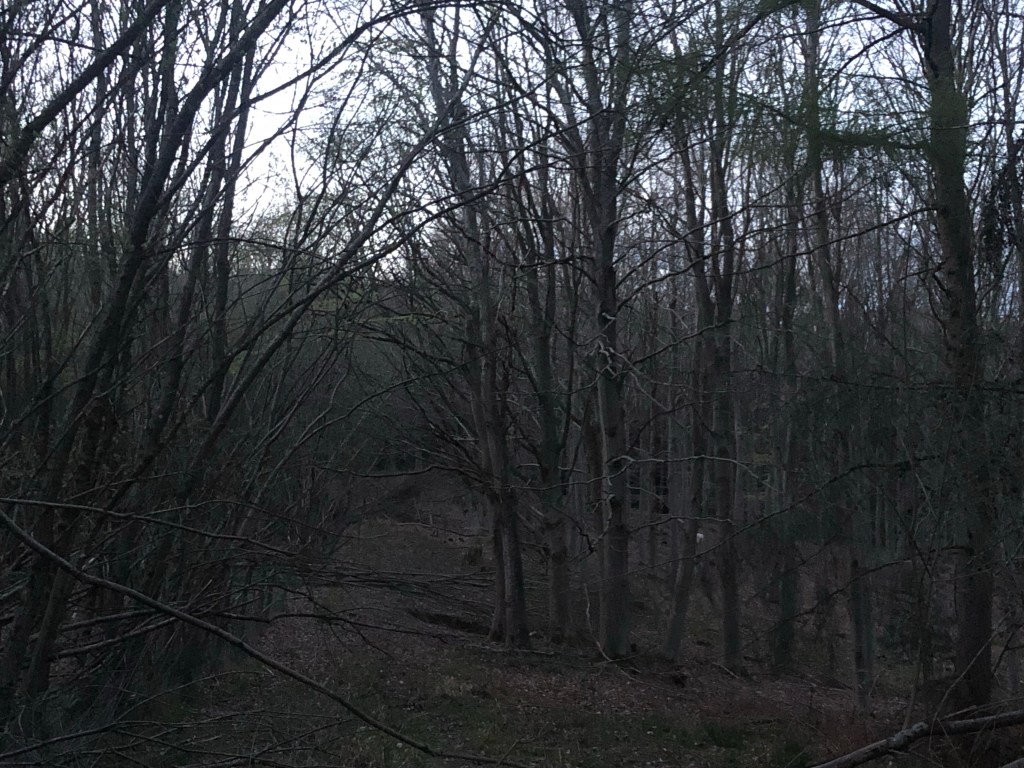

More than a couple of times, I’ve looked over my shoulder to see a roe buck staring back at me. I almost walked right past a couple on my way into town yesterday, and they stood their ground even when I stopped to stare right back. They’re easy to miss at this time of year, blending seamlessly into the starving ferns and leaf-litter, and I might well have missed them more than I’ve seen them. The only obvious sign you get is when they dash off into the woods, their tails flashing white like a signal behind them. When the snow came down in December, they were only too easy to spot. I very nearly missed my train into London because I stopped to let a small herd cross the path into the woods beyond, watching them until they disappeared into the gloom. It wouldn’t be the first time.

During a cold snap like the one we had before Christmas, it isn’t uncommon to see foxes out and about during the day, since the going gets tough for pretty much everything that lives in the forest. Last weekend I saw one curled up asleep in the open beside the Gatwick stream, one eye open and trained on me as I wandered by. Not too many weeks before, I had a close encounter with a younger tod on the edge of town, which was either so accustomed to people passing by or too hungry to care that I was sitting only a few metres away. Plenty of folk passed by without so much as a sideways glance, which is understandable, I suppose – foxes aren’t universally popular for a number of reasons – but the country boy in me can’t help but stop, and look, and listen. Whether or not they’re virus vectors or poultry pilferers, foxes are undeniably beautiful creatures when you get the chance to have a good look at them.

Then there’s all the voices of the Weald. Snatches of conversations in languages at once familiar and unfamiliar. The croak of the ravens that nest somewhere in the forest. The harsh cry of a hulking grey heron as it soars above the trees. The thin rattling wheeze of a wren, and the answering snare drum of a woodpecker. It’s all I can do to keep my head facing forward on my way to and from lessons at work, lest I make my love for these things painfully obvious. In a very real sense, I’ve been playing the same game since I was a schoolboy. That makes it twice as fun, I guess.

Boy, but it feels good to be writing again. I’m out of practice. I’ll report back when I have something to report. BB x