The students have gone home for half term. Silence hangs over the school. The corridors of the boarding house are dark, and a little cold, too. The floorboards creak under my foot with the kind of volume that only darkness can amplify. The dull glow from the torch on my phone casts long shadows. A friend of mine once explored an abandoned hospital on a dare. I did not go with him then, out of some primordial fear of the darkness within. And yet, here I am, haunting the empty corridors of this old house by night, the last man standing. Filling up a water bottle from the cooler on the Year 10 corridor becomes a quest in its own right.

I’ve had a lot of time to think lately. I guess coming out of a long term relationship will do that for you. One of the things I thought I might be able to recover was the fierce reading streak I had on my year abroad, but I just can’t find my mojo for that right now. Time just seems to slip through my fingers when I’m not at work. I wonder what the world does when it’s not working? I guess that’s what television is for, or Netflix, or whatever streaming service is in right now. But then, I’ve never been good at sitting down to movies or TV shows. My brain wants to be involved. There’s a precious few I’d happily watch over and over and over again, but it’s rare that I find a new picture out there that sinks in.

There’s not a day goes by where I don’t feel a genuine fulfilment in my line of work. Teaching is in my blood, a duty that my ancestors have carried out for generations. Knowing that I am the torch-bearer for my generation gives me a sense of purpose that is utterly unshakeable. And it’s not as though that purpose hasn’t been tested over the years. It’s just that, whenever something comes up to shake its fist in my direction, I know instinctively that there’s a greater mission behind it all, and that’s reason enough to persevere – even when my core beliefs are thrown into disarray. I wonder if my great-grandparents, Mateo and Mercedes, ever had such doubts?

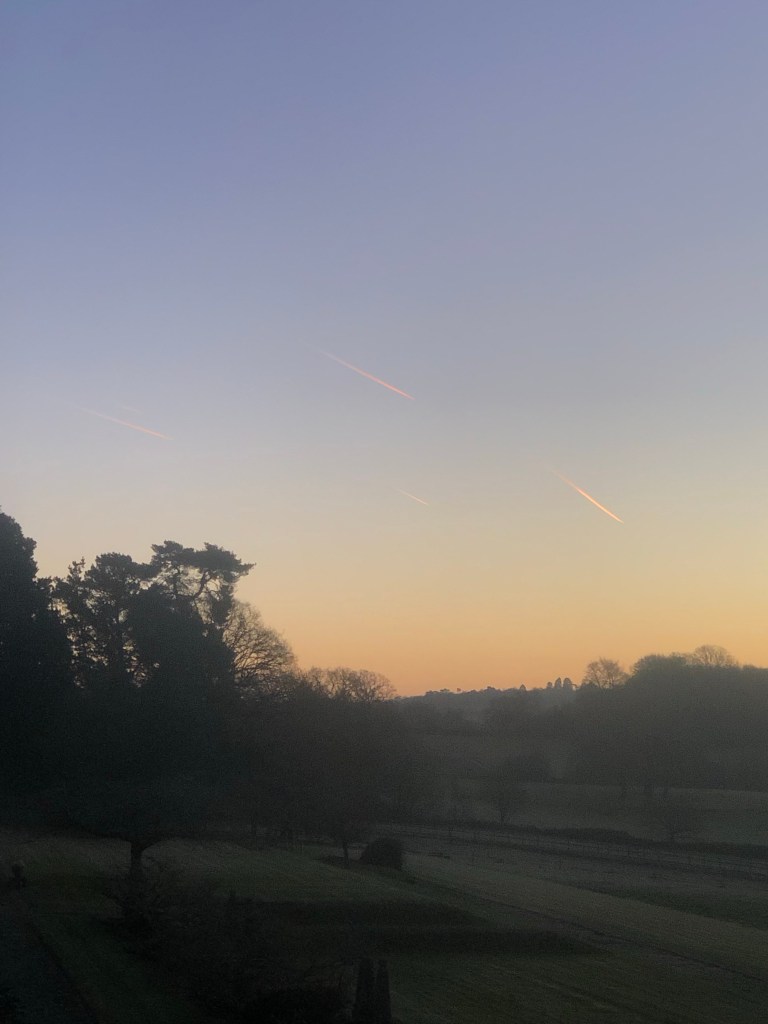

There’s a little owl calling outside. It’s been piping away from the upper branches of the Atlas cedar in the drive for half an hour now. The foxes have been quiet for a week or so now. I suppose their noisy January antics in the front quad are over for the year. Three buzzards were soaring over the grounds the other day during morning break, but none of the students seemed to notice. The redwings and the fieldfares have moved on and the snowdrops are out. The daffodils will be on their heels soon enough. I escaped to Richmond Park a few weekends back, just as the first blooms were sprouting. It was good to see the wide world again, even if only through my own eyes.

The meltwater of the long Covid winter is starting to run. Just like the birdsong and the subtle shift in the light over the last couple of days, change is in the air. Piece by piece, the last fragments of the old world are coming back. At the request of one of my students, I blew the dust off my long-neglected violin and rocked up to orchestra this week. I’m about as good on the thing as I ever was – that is, haphazard at best – but I’d forgotten how much fun it used to be. It’s one of those things that simply slipped through my fingers over the last couple of years.

I think I’ll take up the guitar this half term. A zealous diet of sevillanas have powered me through the darkness of the winter months this year, and I’m done with being able to sing along but never sing alone. At the very least it will give me something to do until my provisional arrives and I finally confront the long-delayed challenge of learning to drive, which I have put off for far too long.

I’m done with playing games. It’s high time I went on another adventure. The Easter holidays aren’t far off, and I could do with some more writing fuel. And spring is always such a hopeful time of year. BB x