Albergue El Texu, La Espina. 17.09.

One of the things I love the most about the Camino is that the planning required, relative to any other holiday, is minimal at best. In most instances, you can pick up your bag, start walking and stop in this town or the next when you’re tired. It helps to know which locations are truly special or worth seeking out, but you can always follow the Camino at your pace. For a teacher like me, for whom planning is a daily and often insurmountable chore, the last thing I want on a holiday is to have to plan all of my movements. The total freedom the Camino provides is one of its greatest blessings.

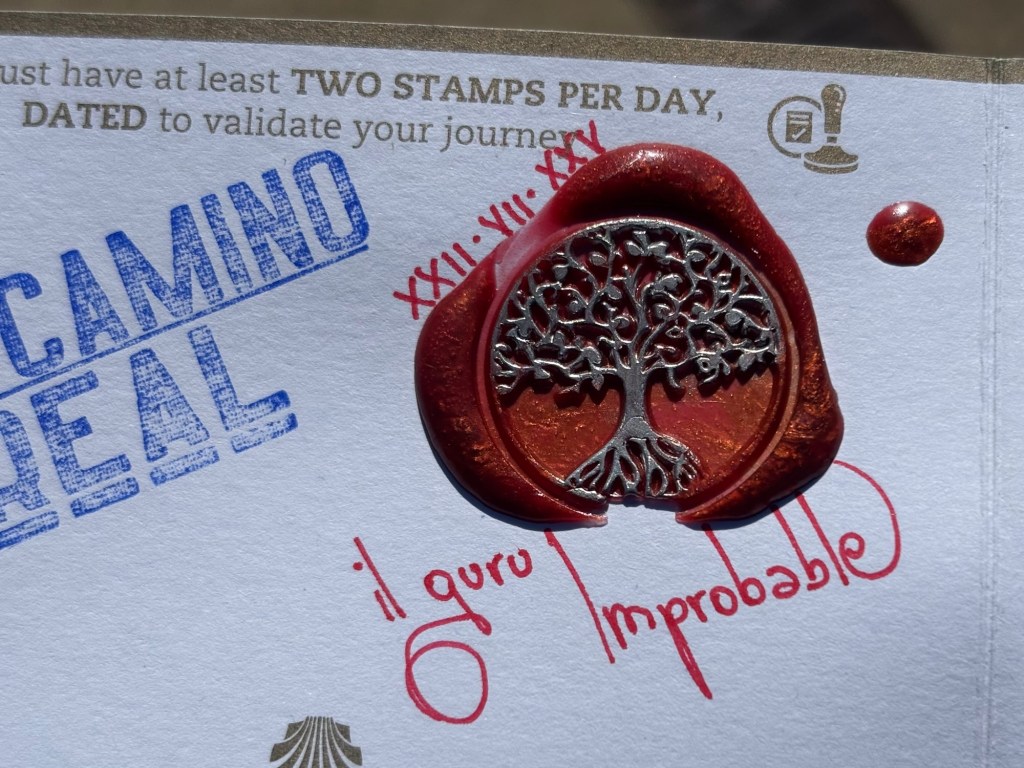

Except when you see signs like this.

I had read a lot about the quality of Bodenaya’s albergue, so I was a little disheartened to see this sign in the window when I got there at around half past one after an arduous climb up from Salas, only to find it was all full – already, and whole hour and a half before it was due to open. Bodenaya, like many albergues along the Primitivo, is small and personal, counting on just ten beds. However, this is not normally a problem if you’re quick on your feet and get there in plenty of time.

Sadly, popularity breeds on itself, and some pilgrims (sometimes with legitimate reasons) feel the need to book all of their accommodation ahead of time so that they can enjoy the walk in peace without worrying about having a bed for the night.

Which is great for them. But not for those of us who have to deal with the disappointment of doing everything right and being beaten to a bed by the eager beavers who would prefer peace of mind over the freedom of the Camino.

Everyone walks the Camino in their own way. That’s a fact. I just don’t agree with the idea of booking accommodation in advance along a route that is one of the few places in the world where you genuinely don’t need to. There are all sorts of other holidays where that kind of mindset is the norm. If I wanted to know where I’d be and what I’d be doing a week or a month in advance, I’d consult my teacher’s planner (or somebody else’s, as I hate writing in mine). Work is planned. The Camino is freedom.

There. I’ve said my piece. Let’s move on.

The hospitaleros at Grado put out a large breakfast spread, so I ate well this morning. I saw a few familiar faces along the road, many of whom had stayed at San Juan the night before after finding Grado’s municipal full (there’s a reason the municipales are often occupied by the younger and fitter pilgrims).

There were a few clouds on the horizon, but the sun rose in a warm, pastel pink, promising a warmer and drier day’s walk ahead. I was quite glad of the rain yesterday, but now that I am armed with more sun lotion, I am not as concerned about another day under the sun’s anvil as I was on the San Salvador trek.

The climb up from Grado is not half as impressive as the descent on the other side, which provides a sweeping panorama of the valleys ahead, all the way to the turbine-topped hills of Pumar that lead to the Bay of Biscay. No Asturian landscape seems to be complete without a small pillar of smoke from some factory or quarry: in this instance, the chalk mines at La Doriga.

Spain’s north has always been its industrial heartland. This is largely due to its abundance of natural resources like iron, copper and coal, which gave the region all the tools it required to build what would become one of the world’s first global empires. There were even gold mines here once, when the Romans scoured their own empire in search of that most precious of metals.

Many of the quarries are still in use, but some have fallen into disrepair, slowly disappearing within the dark forests of Asturias. This one caught me by surprise in the hills behind Salas. The vents through which the chalk must have been shuttled once had long since rusted shut, and vines and thick carpets of ivy had all but concealed the adjacent storehouses, but the tower remains standing. I’ve always been fascinated by abandoned quarries and factory buildings, and Asturias has plenty to explore, even along the Camino.

A short distance from the Camino (at the cost of a 200m descent) is the Cascada de Nonaya, a concealed waterfall hidden away deep in the forest. It’s easily missed from the pilgrim road, but Google Maps is a wonderful thing, so I knew what to look out for. Somebody has erected a metal simulacrum of the Victory Cross of Asturias at its base, so in the absence of a church, I made this one of my stops for a prayer today. It was a very special place: peaceful, dark, ancient.

After the waterfall, the Camino makes a very steep climb up the mountainside before levelling out along the main road towards Tineo. My destination, Bodenaya, turned out not to be – as I had the slightest inkling might be the case – so I shrugged and moved on. La Espina seemed promising, but the municipal albergue didn’t seem to be what it had been cranked up to be online. Then I saw yet another sign for a well-advertised albergue that wasn’t in any of the websites, and the fatalist took over. I know better than to deny fate when it’s trying to tell me something.

El Texu is a beautifully peaceful setup, run by a Dutch family and their volunteers. It wins the award for best shower on the Camino, as far as I’m concerned, and I haven’t even had the Thai green curry that Nani is making for supper! I’m normally a purist for Spanish fare on the Camino, but right now, a Thai curry sounds incredible. I can’t wait! BB x