Albergue Casa del Cubo, Burgos. 22.55.

There’s a grumpy old Spanish guy in the bunk below mine. He made a point of asking me earlier if I snored in that direct, you had better not way that Spaniards do (‘No roncas, eh?’). He put the same question to my two companions just before bed. Well, after a couple of rounds of solitaire in his phone, he’s snoring away down there, along with the Koreans in the bunks next door. Like it matters…! You’d have thought a pilgrim might have learned a little patience by Burgos.

We got lucky yesterday. The Albergue in Atapuerca had a room of six beds so we had a room to ourselves, complete with an en suite bathroom. Along the way we’d picked up Gust, a seventeen-year-old Belgian student who was struggling with his blisters, so we took him under our wing for the rest of the day. There weren’t many restaurants in town, so I bought some supplies from the only shop in town (where the Central American shopkeeper was having a great time rapping to a backing track while I browsed the vegetable aisle) and rustled up a rice and vegetable pisto for the six of us. It felt good to cook for company again. It’s been a while.

We set out shortly before sunrise, finding our way up the Sierra de Atapuerca by moonlight. The sun was not yet over the horizon when we crested the hill, and the soundscape was still very much that of the Spanish night: a couple of scops owls called their piping call from the trees, the high-pitched twittering of a bat occasionally caught my ears and, from somewhere far off, the unmistakeable churr of a nightjar.

We stopped for breakfast in Cardeñuela Riopico at the same place I came with Mikkel, Sofia and Lachlan two years ago. It was just as good as it was then, only this time, I allowed myself to stay and eat rather than tearing off harum-scarum for Burgos on my own.

The signs are still defaced all over the place with images of the Star of David equaling a swastika. They’ve tried to cover them up with pilgrim pointers here and there, but the pilgrim preference for the Palestinian cause is obvious.

We reached Burgos early, despite missing the turnoff for the Río Arlanzón alternative (which I maintain is bloody well hidden, as I’ve now missed that turning twice). The result was at least half an hour of trudging through Burgos’ deeply unattractive industrial estate on the eastern side of the city, so we amused ourselves with a protracted game of Just a Minute, at which Talia proved to be a past master.

It was just before eleven when we reached the albergue, which meant we still had an hour to kill, so we took it in turns to do an ice cream run / sightseeing. Gust parted with us to meet up with his brother. We might run into him on the road, or we might not. I hope he looks after his feet – they were in a bad way.

There was a Mexican wedding or quinceañera or some kind of celebration in town, dressed in the decorated black, white and red that could belong to just about any traditional European country – though the loitering mariachis rather gave the game away.

After an afternoon nap (complete with one snoring Spanish hypocrite), I set out to investigate the Museo de la Evolución Humana, one of the world’s best human evolution museums. I managed to convince the team to check it out, but set out ahead of them to take out some money for the meseta stage (where, if memory serves, ATMs are hard to come by).

I’ll be honest with you. Human evolution is one of those things that absolutely fascinates me. In another life I’d have studied anthropology and primatology. Maybe seeing chimpanzees and mountain gorillas in the wild drove it home all those years ago, or maybe it’s an offshoot of a childhood obsession with all things palaeontological, but it’s genuinely one of my major passions in life, albeit one I don’t talk about so much.

I had a similar experience with the Museo de Tenerife in the spring, but the MEH in Burgos is even more jaw-dropping. The knowledge that I was looking at the real bones of some of our earliest ancestors was genuinely spine-tingling.

The caves of Atapuerca are one of the most valuable dig sites for the bones of ancient humans in the world, with over twenty-eight specimens found to date, alongside a host of other Pleistocene and earlier animals that no longer grace these hills, such as hyenas, jaguars, Irish Elk and the mighty cave bear.

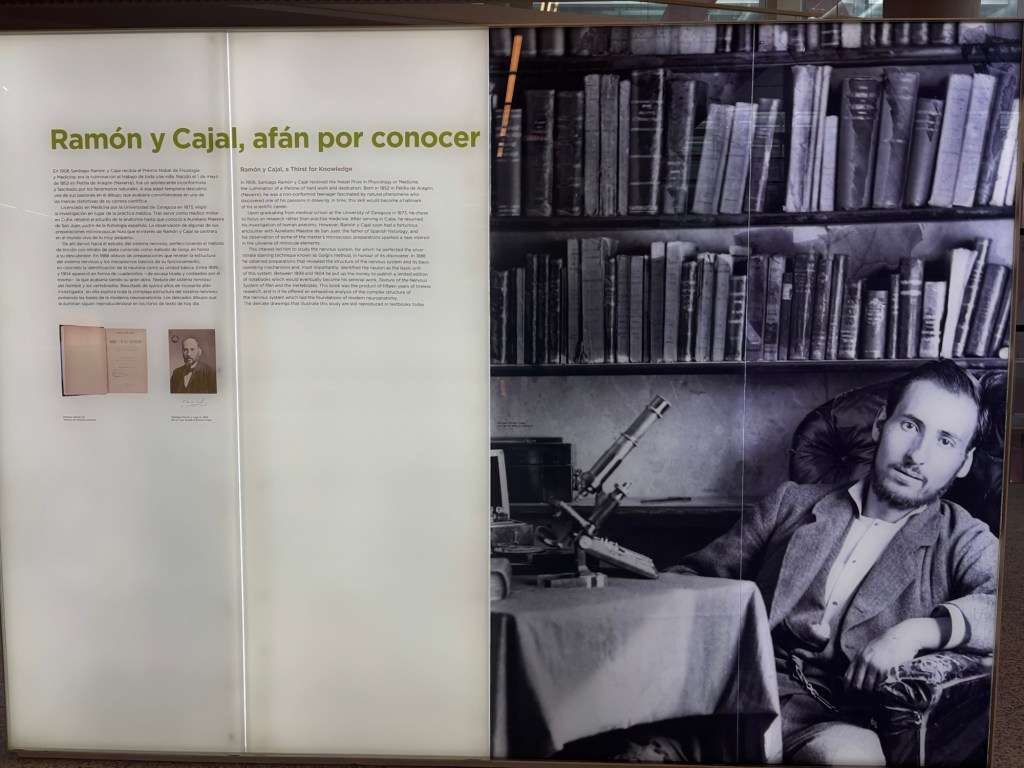

I gleaned everything I could about our ancestors the last time came here in 2013, but there was plenty more to clue up on that if missed before: this time I learned a lot about Ramón y Cajal, Spain’s most eminent scientist and the man who discovered the neuron and its function. Maybe that’s why so many of the main streets and squares in Spanish towns and cities carry his name, connecting people and places like synapses firing daily.

In this morning’s walk-and-talk, one of my companions said she was intrigued by my quest for knowledge. That’s probably the biggest ego massage I’ve had in a while, but I’ll take it. I’m glad to have learned something very new, and it is very much an integral part of my personality to be always on the hunt for a new story, a new tale to tell.

I’ll pick this last one to finish, because it’s getting late, I’m behind on my blogging and the Koreans next door are on the verge of creating an unconscious four-part harmony with their cacophonous snoring.

There’s a small replica on the third floor of the MEH that is, as the plaque reads, quite possibly one of the precious of all the treasures in the collection. It is a mammoth task carved into the shape of a human – but with one strange detail. The head isn’t human at all. Rather, it’s quite clearly the head of a cave lion: stocky, bull-nosed but intensely leonine. It’s known as the Löwenmensch figurine – or the Lion-man of Hohlenstein-Stadel, and its concrete evidence of our ancestors’ ability to imagine around 40,000 years ago. Quite possibly, it’s the earliest evidence for mythology out there: man-beast hybrids remain a fairly common feature of world mythology to this day. Just look at Hinduism.

I’ll have to look into this incredible artefact some more when I get hole. But for now – sleep. I’ll be up again in five and a half hours… unless the Koreans wouldst wake Heaven with their snoring. BB x