Cerro del Sol, Granada. 12.56pm.

They call it the Cerro del Sol, but the sun is hidden behind a white haze of cloud. It covers the snowy peaks of the Sierra Nevada so indistinctly that it’s hard to see where the snow stops and the clouds begin.

It’s pretty quiet up here. There’s a general soar of traffic on the road up to the skiing station of Pradollano in the Genil valley below, but beyond that – and the occasional rev and growl of some larger engine – it’s just me, the butterflies and the birdsong up here. Mostly fritillaries, coppers and marbled whites, though I did see a beautiful swallowtail float by a moment ago, before I put my cardigan over my head to shield my eyes from the white glare of the sun. It shines brighter than the garden Star-of-Bethlehem at my feet. Such a beautiful flower – I’m not sure why I never noticed them before.

I’ve come up here to write – and to heal. I didn’t sleep well last night. Some wounds, it seems, take a long time to mend. So I’m up in the quiet of the dehesa, in the hills east of Granada, soaking in the best palliative that nature can offer. Herself.

The occasional buzz of a fly. The twitter of a pair of pallid swifts racing by. The summery buzz of a grasshopper and the chuk-chuk-chukar of a partridge somewhere in the scrub far below.

A couple of Sardinian warblers are engaged in a territorial dispute in the broom bushes below, rattling off their warnings like Gatling guns. And always and everywhere, I can hear the song of blackbirds – an ever-present symbol of Granada.

This is the Dehesa del Generalife. I suspect the Moorish sultan of old must have come hunting here with his retinue in the days of al-Andalus, as these hills are teeming with small game: wood pigeons, partridge and rabbits (I didn’t see the latter, but this is absolutely their kind of terrain). What a sight that must have been: the Moorish sultan and his hawks, looking up at the snowy peaks of the Sierra Nevada and across the Vega of Granada.

It’s far too easy to see why this place bewitched the Romantics and scores of travelers back in the day, before the modern tourist trade sank its teeth into the place. Well, here’s a corner of Granada they haven’t spoiled: quiet, ancient, magical. Sure, it’s an hour’s hike from the Alhambra, but some things are worth the trek.

On my way up here this morning, I paid a visit to the Capilla Real to see the tombs of Fernando and Isabel, the Reyes Católicos. I figured I’d made the voyage to El Escorial to see the other kings and queens of Spain, so I ought to pay my respects to the ones who started it all.

A surly security guard at the door gave me a long, hard look as he waved me in and warned me not to take any photos. I indicated the notebook and pencil in my hands and asked if I could sketch. He didn’t reply. His stoney expression might have been cast in the same marble as the sarcophagus behind him. I guess he didn’t see the joke.

It’s funny how some people get so uppity about tourists taking photos, but nobody ever seems to mind a sketchbook. I’ve stood on street corners for up to an hour sketching and nobody bats an eyelid, but whip your phone out in some places and there’s hell to pay.

I bought a couple books in the gift shop (I needed some reading material and they were relatively cheap, by Spanish standards) and climbed back up the Carretera Empedrada through the Alhambra forest, where I stopped to check in my flight for next week and sort out tomorrow’s bus to El Rocío. An enormous tour group of German pensioners ambled by. There must have been at least sixty of them, perhaps more. They were followed not too far behind by two outings from a Spanish private school – recognisable by the distinctive shade of blue uniform that is so popular with colegios privados out here.

That figure of eight thousand a day I heard yesterday really does seem more believable when you stop for a while and watch the tourist traffic.

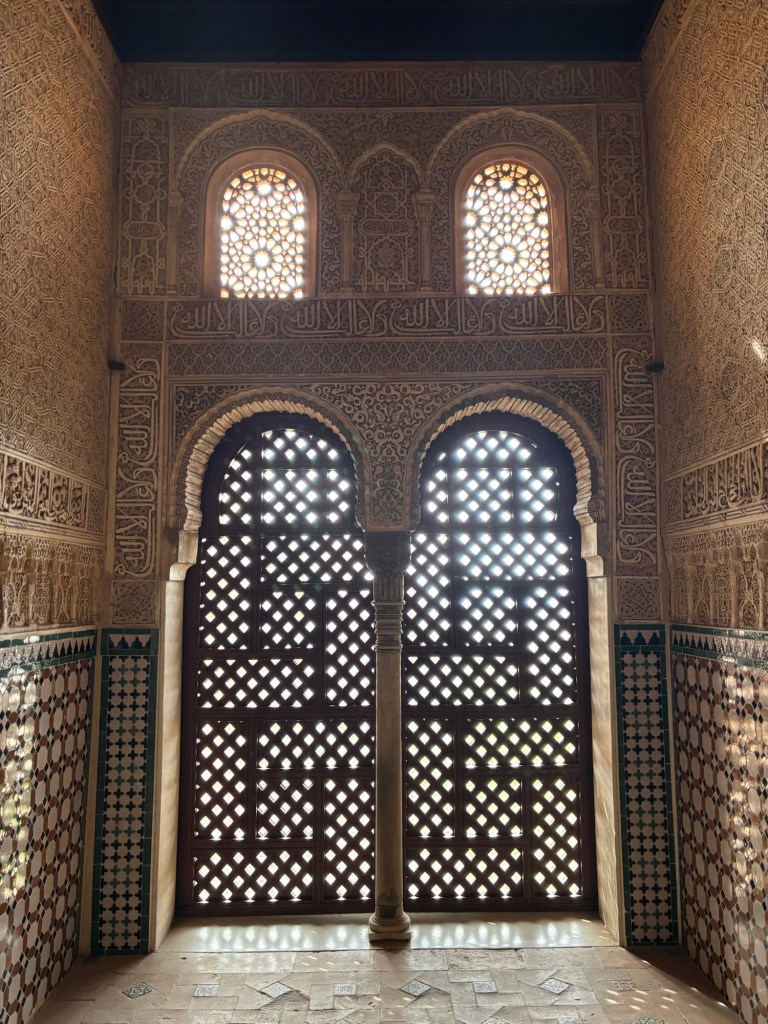

A short amount of time in the wilderness was enough, so around midday I dusted myself down, left the swallowtails to their games and headed back the way I came. When I came to the Alhambra, I took the right fork this time, following the Cuesta del Rey Chico down along the Acequía Real. It’s a steep descent (and an even less forgiving ascent) but it follows one of the main water channels right down to the Darro, so you’re accompanied all the way down (or up) by the most beautiful sound of running water. The Alhambra’s watchtowers serve as waymarkers: the Tower of the Captive, the Tower of the Judge, the Tower of the Peaks, and the Tower of Comares, the seat of the Sultan of old. The Sultan and his family may be long gone, but their waterworks are still running as they did then, six hundred years ago.

As I came down the hill, a thought came to me that had come several times now since I arrived in Granada. Who would not defy the world for such a place? Who would not have fought off the very hordes of Hell itself to defend this paradise on Earth? And what greater heartbreak can there be than to be banished forever from a place that was more than just a home, to know in the very depths of your heart that you had lost the keys to Heaven itself?

It’s not hyperbole. I’m merely paraphrasing the laments of the Andalusian poets of old when Granada fell to the Christians in 1492. It puts my own petty broken heart into a much-needed broader context. There was a sense of loss here far greater than anything a single heart can withstand. I have felt the tremors of it before in Sevilla and Córdoba, but nowhere stronger than here, the last bastion of the Muslims in Spain. Such a raw outpouring of emotion leaves a mark. Ghost stories would spring from it in more credulous parts of the world. Here, it is an indistinct melancholy – something in the air that once was, and is lost forever in all but memory.

Writing two hundred years before Granada’s demise, al-Rundi’s lament for the fate of Sevilla captures the grief:

A pretty lady, splendid as sunlight,

Her beauty just like coral and jewels bright,

Dragged off by infidel for rape most vile,

Her heart perplexed, she’s crying all the while.Abu al Baqa’ Al-Rundi, Ritha al–Andalus

I wonder how the Muslim tourists to the Alhambra feel upon seeing such a place? There do not seem to be as many as I remember.

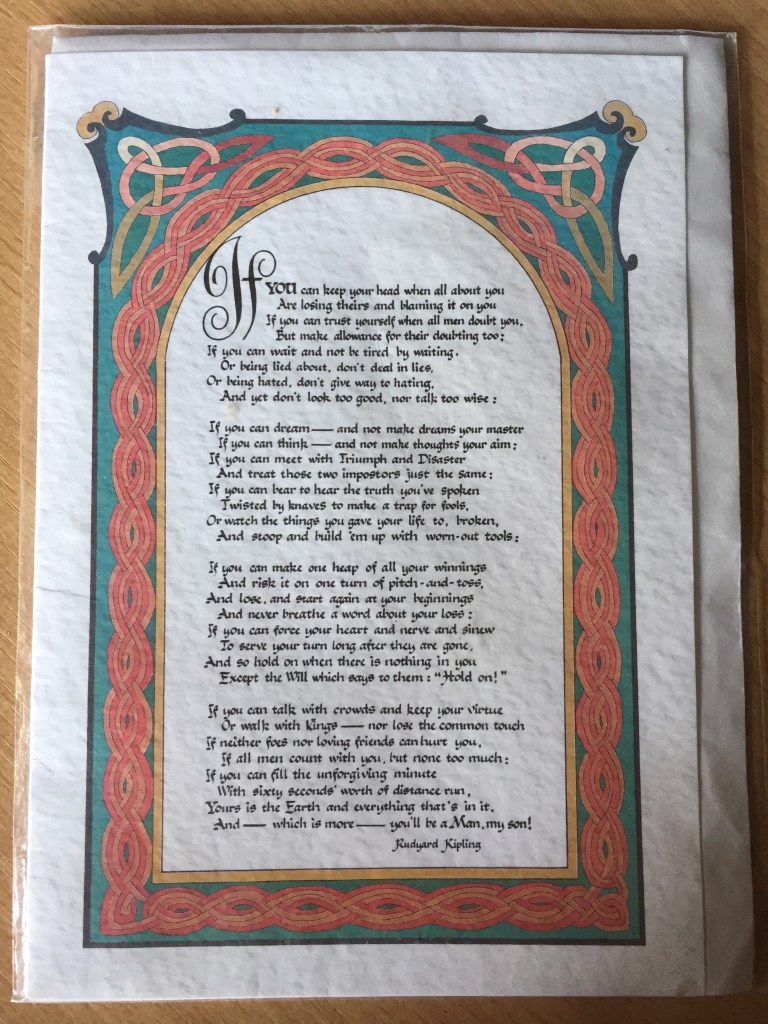

One week remains. Tomorrow, I make for a place that has always been close to my heart: my Granada, my Jannah, my paradise on Earth. It looks like it will be a rainy weekend. But nothing could put a damper on the thought that I will see that place again, after all this time: El Rocío. BB x