I at least made an effort to wait for my fellow pilgrims this morning, but impatience got the best of me. When half an hour passed and all but a trickle of the pilgrims from my albergue had come and gone, I gave up and set out for León. I wasn’t in any particular hurry, but a conversation over dinner with an Italian veteran of the Camino (this would be his tenth rodeo) had me reflecting on his words: you can never do the Camino at any pace other than your own. Well, there I was, trying to match the speed of another pilgrim or two. In the end I have to be true to myself. So off I went.

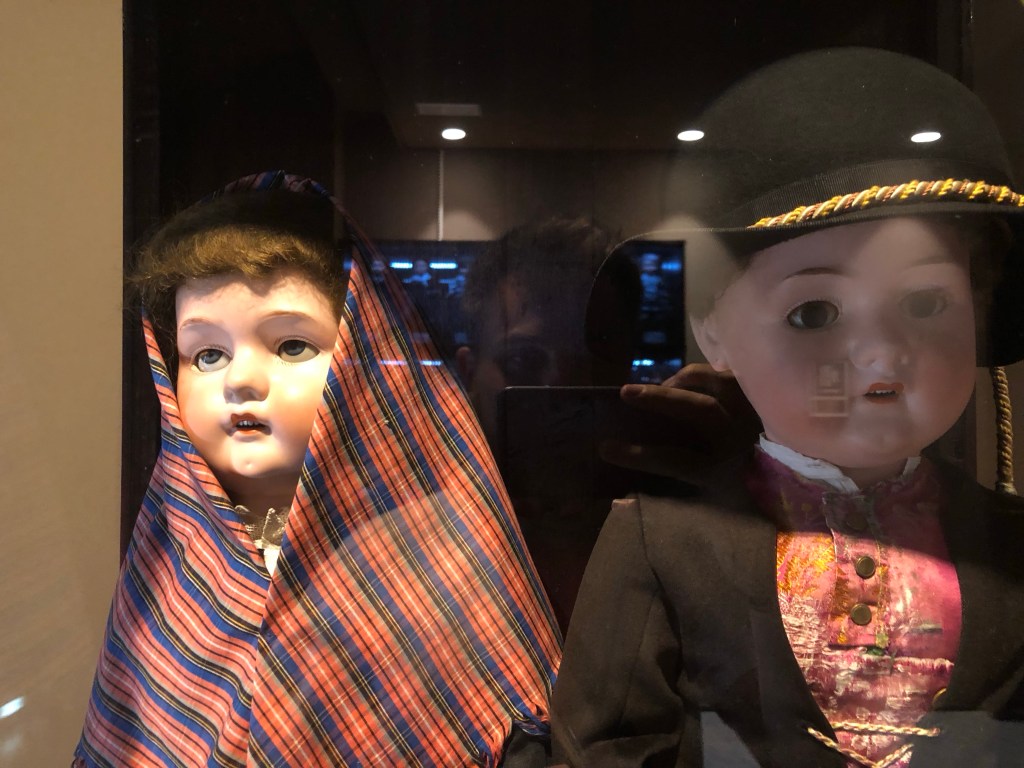

It’s not far from Mansilla de las Mulas to León – four hours, tops, though I could probably have done it in a little over three. But for the Museo de los Pueblos Leoneses, which I really did want to visit, I might have pushed on yesterday and done two days’ work in one. But I am being kind to my feet, seeing so many pilgrims in varying states of deterioration, and so I made my way leisurely this morning.

The approach to León is not the most scenic of the Camino by any standards – most of it passes through an extensive suburban industrial estate – but there was still some magic in the sunrise when it came over a roadside field where a large number of storks were flying in to feed from all directions.

I dawdled for a bite to eat in Arcahueja, still in the hope that a few of my pilgrim companions would show up. They must have been tardy this morning, because I never did see them. Instead my French got a serious polishing over a conversation with Jean-Paul from Carcassonne and Adine from Versailles. It might be lacking the instant spark of my last Camino, but if I remember this leg for one thing, it will be the constant linguistic gymnastics – I don’t think I’ve had to bounce between languages so often ever before. It’s bloody good fun!

I reached the outskirts of León at around 10 but it was almost 11 by the time I reached the Benedictine albergue, my digs for the night. Of the old guard, only Sean the Irishman and Alan from Rennes elected to stay here – I haven’t seen anybody else I know. It’s equally possible others will join here. It’s an established fact that the road gets seriously busy from Sarria, so that’s something to look forward to.

For future reference, July is – surprisingly – low season. The Camino is at its busiest in May, June and then August and September. For whatever reason, July is a quiet month on the Camino. Well – now I know!

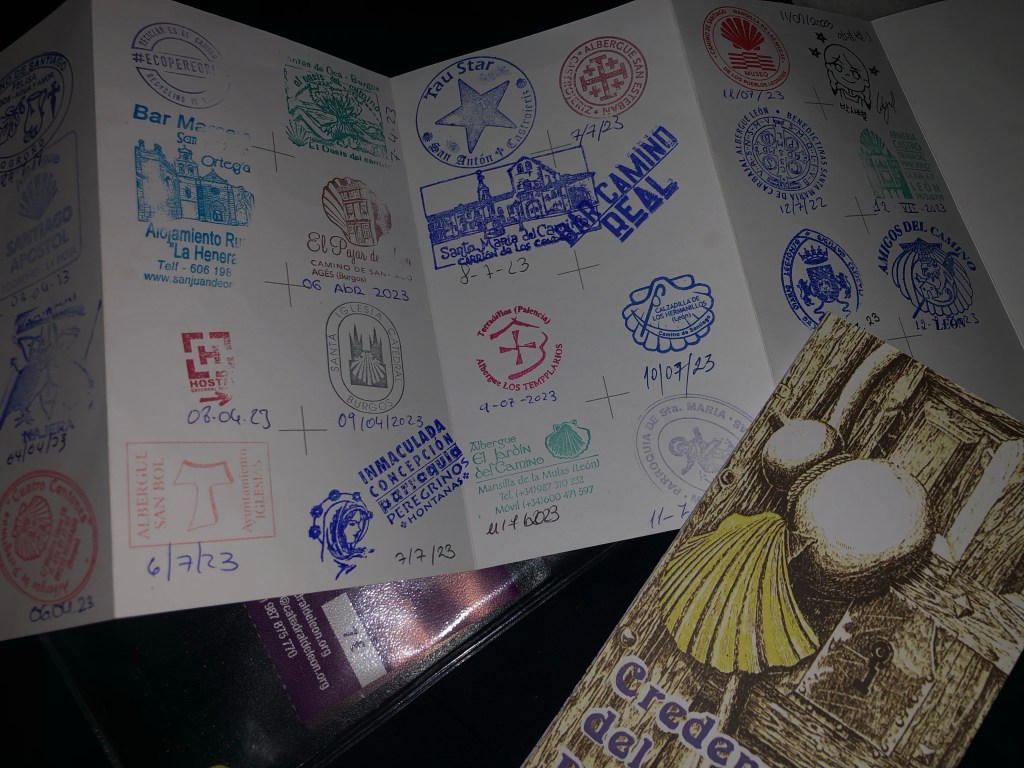

León’s enormous cathedral was under heavy scaffolding the last time I visited so I thought I’d pop inside. It’s pretty magnificent as cathedrals go, but I still think that spending so many hours of my childhood in Canterbury Cathedral has left me somewhat jaded when it comes to cathedrals. More importantly, it produced another stamp for the pilgrim passport, which is now dangerously close to completion…

I had a snack lunch in the kitchen with a very cheap spread from a nearby Coviran and had a short siesta to while away the hours before everything reopened at 6pm. Conscious that the Galician stage requires a minimum of two stamps per day (or something like that), I went to the Asociación de Amigos del Camino de Santiago to seek a new credencial. It wasn’t immediately obvious, but rather, tucked away in an office on the fifth floor of an unassuming tower block above a bank near the Plaza Santo Domingo. The socios inside, however, were wonderfully friendly and I had a good long natter after their initial confusion over my names (Spaniards always seem to have issues gettin their heads around the British custom of middle names). Armed with a new credencial (and with my mood improved by a humorous argument about whether or not to stick the two credenciales together, which was a bone of contention between two of the socios), I am now prepared for the final two stages of the Camino. Bring on the stamps! BB x