Finisterre. The End of the World. It’s a fitting place to end the Camino, which can sometimes feel like it really does go ever on and on, down from the door where it began. Well, here we are at the end of the road. Kilometre 0. My great quest for the summer is over.

With a good thirty-two kilometres between O Logoso and the seaside town of Fisterra, Simas and I set off early this morning. One last six o’clock start, an hour or so before the dawn, to end the Camino as it began: in the dark. The churring of nightjars echoed in the forest around us as far as Hospital, after which the road climbed up over a treeless moor before slowly beginning to descend toward the clouded horizon beyond.

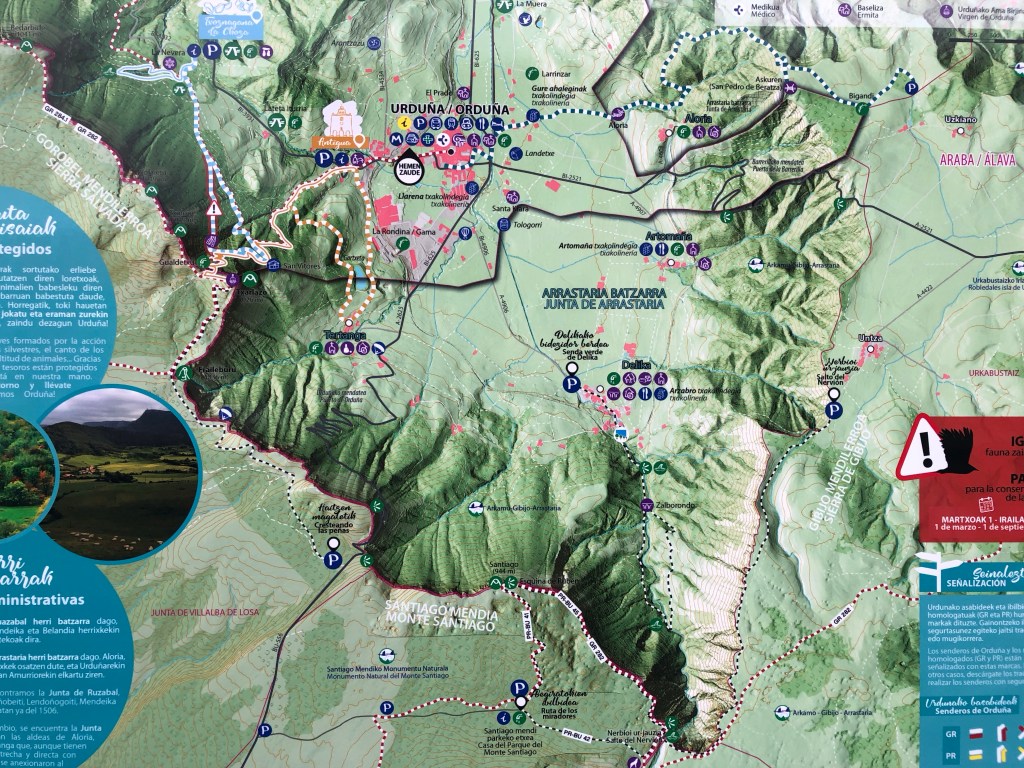

We passed a few alarming signs declaring ‘territorio vákner’, which didn’t make a lot of sense until we stumbled upon an enormous sculpture in the woods of a wolf-man. The ‘vákner’ was, according to 15th century pilgrim lore, a Galician forerunner of the werewolf legend, and one of a number of terrible beasts that beset pilgrims in the forests after Santiago. The more you know!

Less fantastical, though by no means less legendary, we found a Tupperware box on one of the stone walls deeper in the woods containing a number of breakfast options: yoghurts, bananas and pastries, complete with plastic spoons in case of need. The invisible benefactor, an eleven-year old local boy, was trying to raise money for a trip to Madrid. I tipped him generously via his piggy bank and enjoyed the breakfast I otherwise might not have had this morning. What a little angel!

Shortly after leaving the forest, as though out of a dream, the sea came into view. I have been so excited to see the sea after three weeks on the road and saving it as a reward for the final day was definitely the right thing to do. We came down into the busy former whaling town of Cee and had a proper breakfast of churros con chocolate, for the princely sum of 3.75€. And that’s including Simas’ café con leche. I’m going to miss how cheap this country is.

Having killed an hour, we pressed on north and west through Corcubión, which was being kitted out for a medieval fair. We detoured a little to see the coast, and were guided back to the Camino by a friendly local afflicted by throat cancer, who pointed us back to the road using a robotic device at his throat. We had not gone much further than Estorde when the sun came out, causing the white sands of the beaches to shine out like a beacon. Given the gloomy forecast for the rest of the day, we took a chance and detoured once again to one of the coves, finding it deserted. And boy am I glad we did!

This was what I walked five hundred and sixty kilometres for: truly, the treasure at the end of the rainbow. There were no pots of gold, but there might as well have been diamonds in the water: each gentle wave kicked up clouds of white sand that glittered in the sunlight like a thousand twinkling stars. Sand eels and mullets darted in silver shoals nearby and a sandpiper scurried up and down the shoreline at a safe distance from us. The way the forests practically tumble right into the ocean, ringed with beaches that shine a purer white than anything the Mediterranean can muster… I’m amazed the Galician coast isn’t as heavy a hitter on the tourist trail as the Costa Brava. Amazed – and grateful. Because from some of the graffiti on the town walls – no a la Marbellización – it’s pretty clear the gallegos don’t want it to have that level of fame either.

A special mention should be made for saint number two of the journey: Nacho, a Valencian who had set himself up on the hill overlooking the Langosteira beach with two paella dishes full of home cooking that he was handing out to passers-by, free of charge. He was quite insistent on this last point, maintaining that though he was between jobs he had enough money by the grace of God to live on, and wanted to share his luck with the world. We had a good natter about what constitutes a real paella, but above all it was really uplifting to meet such a good-hearted man from my grandfather’s region – because while I’m proud to have Manchego heritage, my grandfather was actually born in Torrevieja, which means my immediate ancestry is actually Valencian. Go figure!

We reached Fisterra just after one and checked into the albergue municipal, which was already quickly filling up. It is as well that we did, too, as it landed us the final stamp in the credencial and an additional compostela for completing the final 100km of the Camino. After a quick nap we grabbed a table at O Pirata, a very characterful port-side seafood restaurant whose staff (and hangers-on) really did give off the right vibes as a motley crew rather than a team of restauranteurs. Between our waiter, who might well be the fastest-talking man in Spain, the chef with his black bandana and earring, and the three musicians sat outside, strumming guitars and clapping along – not to mention the seafood itself, which was delicious – it was easily the best meal of the whole Camino. Best of all, they threw in a free ego massage, telling me it wasn’t just the La Mancha shirt that gave away my Spanish heritage but also my ‘actitud’. I’ve actually managed to convince quite a few Spaniards that I’m a native on this Camino, which is a huge thing for me. I’m one step closer every day to reclaiming my heritage!

After lunch, Simas went back to the albergue for a siesta but I fancied a wander around town before the forecasted rain came down. What I thought might be a museum/aquarium in the harbour turned out to be an open-air working fishery, where a raised walkway lets you look down on the fishermen at work, processing and sorting the morning’s catch. It’s a brilliant idea and a fascinating way to have a look-in behind the scenes – especially after enjoying the fruits of their hard work for lunch! One chap was sat measuring the many thousands of razor clams and sorting them by weight, which looked to be a truly Sisyphean task: it must take hours to finish before the next haul arrives and the task begins again.

Stamps and celebratory seafood platters aside, you can’t say you’ve completed the Camino unless you really do go all the way to the end of the road, which is another three kilometres down the coast to the windswept cliffs of Cape Finisterre. The pictures imply a lonely lighthouse watches the cape, but it’s also home to a hotel, a bar, a car park and a couple of souvenir shops, so it’s not as remote a spot as you might think. The steep banks of the cliffs were pretty busy when we got there, with both pilgrims and tourists from various parts of Spain, and it was a good place to bid farewell to several pilgrims I have crossed paths with on the road: Alan, the wannabe hostalero, and the French team of three, Jean-Paul, Adine and Philippe; as well as Liza the Belgian (whose wish was granted by beating me to the Cape) and Catherine the German (who wins the award for the most random encounters along the whole Camino).

I found a quieter spot lower down and sat there for a while, watching the waters of the Atlantic below. It was a good place to reflect. I let go of a lot of things at last, letting them drift from my heart through my fingers and out across the ocean. Down below, gulls wheeled and cried around the cliff edge while a sparrow and a redstart made a few dizzying sallies across the precipice. My eyes were trained on the waves, searching for one thing in particular, and after half an hour – in the wake of a fishing boat – I saw what I was seeking. Not the lonely gannet or flight of shags that rounded the cape, but a fleet of shearwaters, an endearing and highly acrobatic seabird that truly lives up to its name, flying low over the water with the tips of their wings slicing the tips of the waves like blades. I was far too high up to tell what kind they might be, but I imagine they were Balearics, given their size and number.

If the ghostly harrier and quail were the spirits of the early Camino, it’s the handsome shearwater that marks its end. While I’ve walked most of the Camino alone, I’ve had companions every step of the way, from the merry stonechats that have been with me every day to the nightjars that have kept me company in the twilight hours. If you can put a name to the sights and sounds all around you, you’re never truly alone on the road.

If you kept going in a straight line from here, you’d reach Long Island and perhaps even New York City. But unless you have the stamina of a god and the strength to match, that’s simply not possible, so here the road ends at last. I penned the words ‘Llévame contigo’ (Take me with you) into my faithful stick and planted it in the earth just behind where I had been sitting. I hope somebody does take it with them, and that it brings them as much joy and support as it has brought me.

I thought of its predecessor, and the feathers that had made it so memorable to other travellers on the road, and as I did, a couple of ravens suddenly appeared on the wind, soaring in circles around the cliffs below. One of those feathers I carried before belonged to a raven – so perhaps they were with me all along in spirit. I’d like to think that. According to legends of old, it was a raven that first brought the light of hope into the world.

Well, that’s a wrap. It’s now twenty to eight on Friday 28th August. The rain is falling outside and I’m booked on the 11:45 bus back to Santiago. I’m going to find myself a café near the harbour and do some writing while I wait, in this seaside town with which I have fallen in love. Galicia has been beautiful since O Cebreiro but its coast has utterly enchanted me. It feels like home, and yet like Spain at the same time. It feels like Edinburgh, Hythe and Olvera all rolled into one.

I will come back. There is more to the Costa da Morte than I have seen. I must come back. BB x