Andén 13, Estación de Autobuses de Cáceres. 13.29.

That last post was a bit lacklustre. I can’t be at the top of my game all the time, but I’ll admit it is hard to write convincingly about my favourite topic – nature – when the rain kept me indoors for most of the day. I got out for a bit during the evening to have dinner at Mesón Troya, one of the restaurants in the square (usually a place to avoid in larger towns, but not so here), but beyond my short sortie beyond the castle walls, I didn’t get very far yesterday. Instead, I contented myself with watching the stars from the hilltop and counting the towns and villages twinkling in the darkness of the great plains beyond: Monroy, Santa Marta de Magasca, Madroñera, and the brilliant glow of faraway Cáceres.

Morning summoned a slow sunrise into a cloudless sky. If I had brought walking clothes, I would have set out across the llanos on foot – but Chelsea boots, a smart winter coat and bootcut Levi’s jeans don’t exactly make for the most comfortable long-distance fare, so I erred on the side of caution and took a stroll into the berrocal – the rocky hill country south of Trujillo.

Idly, I set my sights on a restored 17th century bridge some five kilometres or so from town, but I was quite happy to wander aimlessly if the path presented any interesting forks.

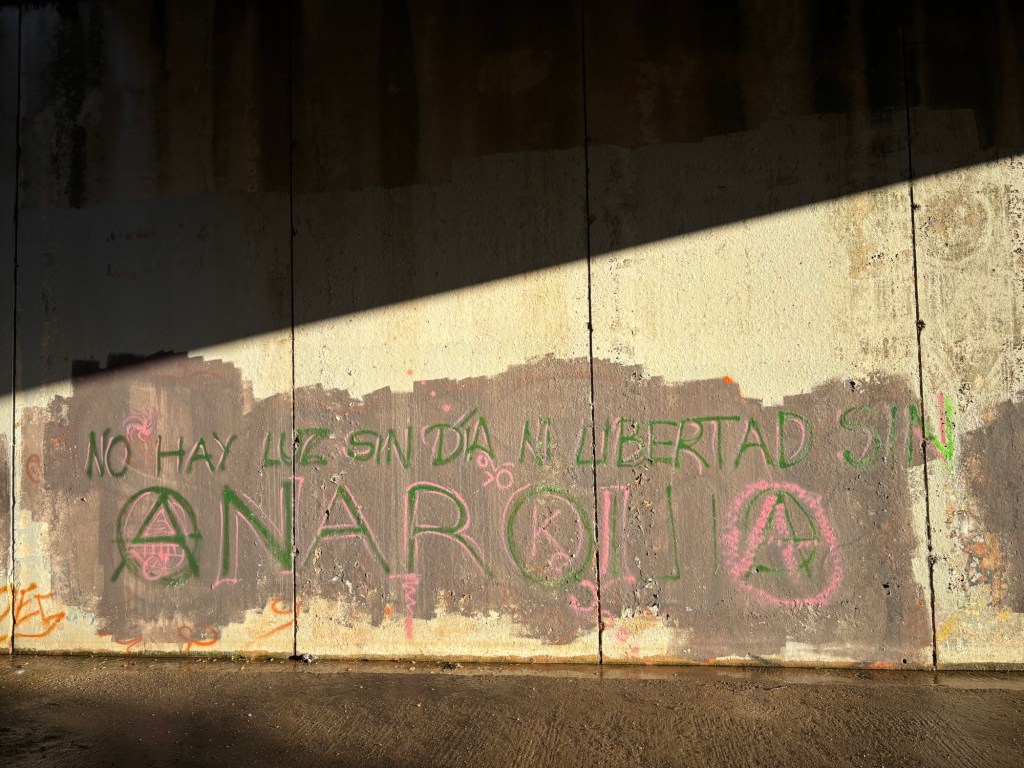

My working life is so full of tasks that require forethought and planning that it’s nothing short of liberation itself to have that kind of absolute freedom that I crave: the freedom to do or not do, to turn back or to push on, to take this road or that, without any thought as to the consequences (beyond the need to get back in time for the bus). A freedom that becomes maddening when it’s taken away from me, like it was in Jordan, all those years ago. It’s a hardwired philosophy that I’ve become increasingly aware of as I’ve grown older, bleeding into my views on speech, movement and identity – and massively at odds with most of my generation.

Perhaps it’s an inherited desire for freedom from my Spanish side: I do have family ties to Andalucía, a region that once made a surprisingly successful bid for anarchy, and my great-grandparents quite literally put their lives on the line to make a stand for freedom of thought under Franco’s fascist regime.

Or perhaps that’s just wishful thinking. Either way, it’s hard to deny just how important that sense of total freedom is to me. Maybe I’m more like the Americans than I thought.

I didn’t make it as far as the bridge. The full day of rain from the day before had done more than dampen the sandy soil and form puddles and pools in the road. It had also swollen the Arroyo Bajohondo to the size of a small river. It didn’t look particularly bajo or hondo, but I didn’t trust the stability of the soil underfoot and didn’t fancy making way to Mérida with soaking jeans up to my knees for the sake of a tiny bridge, so I turned about and returned the way I had come.

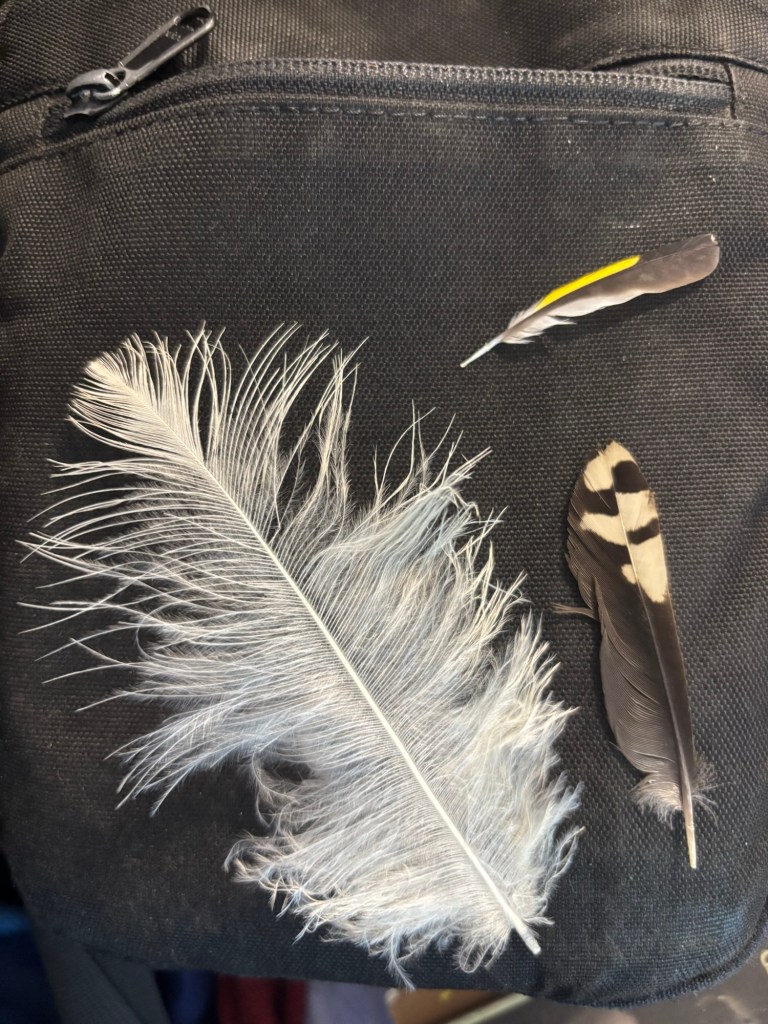

Without a car at my disposal, I couldn’t make it out onto the plains, home to Trujillo’s more emblematic species (bustards, sandgrouse and stone curlews), but the berrocal was teeming with wonders of its own. Hoopoes, shrikes and stonechats watched my coming and going from the rungs of rusting farming stations, while woodlarks and skylarks ran this way and that along the stone walls that marked the boundaries of cattle stalls along the way. A flock of Iberian magpies kept me company on the way back, their jaunty black caps almost shining in the sunlight, and I nearly missed a lonely lapwing sitting in one of the fields – a curiously English sight in far-flung Extremadura – before it took off on powerful, bouncing wingbeats.

Speaking of powerful wingbeats, I was practically clipped on my way down to the arroyo by three hulking shapes that flew overhead. I clocked one as a griffon – there are few silhouettes I know better – but I had a feeling the other two might have been black vultures – something about their colossal size and the heaviness of their beaks. They seemed to have disappeared by the time I turned the corner in pursuit, which is hard to imagine for creatures with a wingspan of around 270cm.

A change in perspective always helps, however. I found all three on my way back, sunning themselves on a granite boulder not too far from where I’d first seen them. I suppose I’d have had my back to them on the way down. And what an impressive sight they are! Please forgive the photo-of-a-photo until I get home and can replace the image below with the real one from my camera, which always outperforms my phone when it comes to anything that requires distance.

Even with the full day of rain, I’ve scarcely had a moment out here where I’ve felt lost or alone. Spain works an incredibly potent magic upon me, whether it comes in the form of the music of its native language, pan con aceite y tomate, the immense blue skies of Castilla or the spectacular sight of its vultures, forever and always my favourite sight in the whole world.

I conveyed this jokingly to an old lady from Villafranca on the bus. She gripped my arm with a talon that the vultures might have envied and told me in no uncertain terms to “búscate un trabajo aquí”. It does feel like the universe is trying to help me to set things right and come back. But I have to get it right. I need this to work this time. So – fingers crossed.

If I could spend the rest of my life in the passing shadow of the vultures, I’d die a happy man. BB x