Cape Finisterre, 20.11.

Galicia provides. Happiness writes white but the white light is brilliant, like the sands that run along the length of the bay beneath my window. Like the feathers of the gannets and terns that dance above the face of the water. Like the sparkling reflection of the sun as it sinks below the horizon along the 42nd parallel north, disappearing beyond the Atlantic, beyond Chicago, beyond the end of the world.

Madrid feels a world away. I caught the early AVLO train from Chamartín and joined a modest number of passengers on the three hour journey to Spain’s north-westernmost region. The railway line tunnels under the snowy peaks of the Guadarrama before racing across the featureless plains of Zamora and then, slowly, climbing into the wooded hills and craggy moors west of Astorga before rolling through the deep valleys of Galicia proper. Spain is one of those countries that alters radically as you travel through it, and the Madrid-A Coruña train is a very good way to prove that point.

I arrived in Santiago de Compostela with a couple of hours to kill before the bus to Fisterra, so I wandered into town and sat in the main square in front of the cathedral for a while. A few school groups posed noisily in front of the cathedral, while exhausted pilgrims sat at the feet of the pillars, soaking up the sunlight to recharge their batteries. There aren’t as many now as there were during the summer. I guess that’s to be expected. The year I made the trek, 2023, was also a delayed holy year, the first since the COVID-19 pandemic shut the Camino down, so the numbers were especially high.

I wonder how far these bold pilgrims had come this year. What friends did they make on their journey? What memories will they take away with them forever? Did somebody watching from the sidelines wonder that about me, years ago?

The bus from Santiago to Fisterra is almost as long as the train from Madrid, but it does travel along one of the most scenic routes in the whole country. To reach the famous cape, it first has to pass through all the towns and villages along the coast, fording the great rías that weave through the cliffs on their way to the sea. The sun came out from behind the clouds just as the cape came into sight, and the whole coast seemed to come to life: the yellow flowers of the gorse shone like gold, the sand beneath the shallows glittered like jade. My heart did a similar leap once when I saw the silhouette of Olvera, my old hometown, for the first time in seven years. It made me smile to think that this place had joined that pantheon.

I arrived early, so I went down to the beach to soak up the sea air for a while. Fisterra is so special to me because it combines the two sides of my heart: the sounds and smells of the sea from my childhood in England, and the language, cliffs and mountains of my adult love for Spain. Mountains take my breath away (especially the craggy limestone kind) and marshes hold a special kind of rapture for me, but I think I will always come back to the sea when I need to feel whole again.

As I watched, a sandwich tern flapped into the little bay and started diving for fish. It was a beautiful sight to see, for the waters are so clear here that I could see the bird’s brilliant white form beneath the water after it had dived, moving like a living arrow. After five attempts it speared a shining silver fish and took off to the south with its catch in its beak. I realised the path on Google Maps didn’t actually exist and beat a quick retreat to the hotel for check-in.

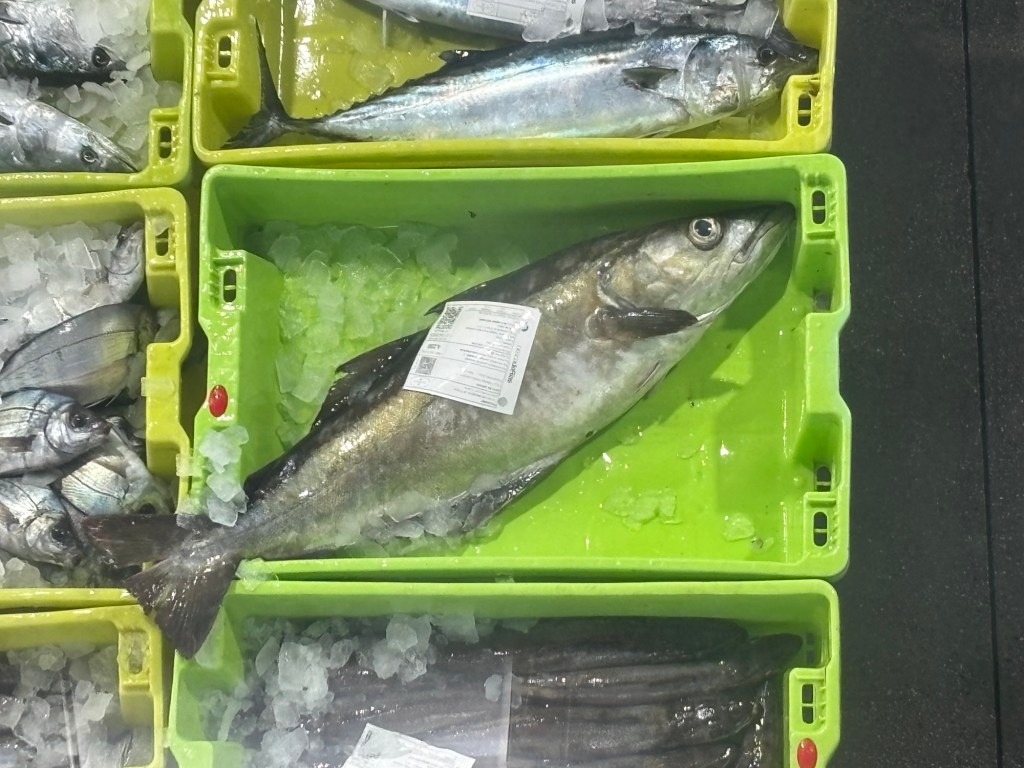

The last time I was here, I only saw the town’s fishery out of hours. I got lucky this afternoon: on my way to the cape I dropped in and caught the daily auction (or lonxa) in full flight. Crates of hake, mackerel, red gurnard and more than a dozen other species I learned to identify as a kid went to the highest bidder in one of the mildest mannered auctions I’ve ever seen (though, to be fair, I haven’t seen that many auctions). Some of the larger fish had QR codes slapped on the sides linking them to the fishermen who caught them, I suppose – my camera didn’t reach far enough to tell.

On one side of the room, crates of sea urchins were stacked fifteen high. I didn’t see any percebes (the region’s famous goose barnacles), but then, the manner by which they are collected is very different indeed, so that’s hardly surprising.

I left before the giant anglerfish went under the hammer. I’d have been curious to know how much that went for.

I called home from the cape and said I’d be back before sunset. It’s now fifteen minutes to sunset and I’m still here, but I’m glad I stayed. The weather here is so changeable and this might be my only chance to watch the sunset from the cape, as it was rained off the last time I was here. A small cohort of like-minded pilgrims and locals have come out here with the same idea. A couple of noisy Spaniards made a pig’s ear of taking a highly choreographed selfie nearby, much to everyone’s frustration, but they’ve gone now, and it’s been nothing but the sound of the waves for the last twenty minutes.

I’m going to stop writing now. The sun will be sinking below the horizon soon and I want to appreciate every second as it does. See you on the other side. BB x