AVLO Carriage 4, Loja. 17.40

Andalucía hurtles by a in a blur of olive green and marbled brown. I’ve never seen it so green: all that rain Spain must have had last month has completely transformed the place, turning the golden fields of my memory into a paradise on earth. I could hardly ask for a better welcome home to the land of my childhood.

Landmarks sail past the windows like ships with friendly colours. There’s the jagged spires of El Torcal, high above Antequera, the first place that genuinely inspired me to write a book set in Spain. There’s the Peña de los Enamorados, a lonely bluff rising out of the fields where, legends tell, a Christian knight and a Moorish princess hurled themselves to their deaths rather than live divided by their warring faiths. There’s the limestone massif of Loja, crowned with wind turbines, their blades motionless in the afternoon air. And there’s the reason why they’re stood so still, standing in awe: the Sierra Nevada, dwarfing all the other sierras for miles around, covered in a vast blanket of snow. If the sunset is good, I will try to snag a spot at the Mirador de San Nicolas at just the right moment tonight, when the setting set sets the snowy peaks of the Sierra ablaze behind one of the most beautiful buildings in the world: the Alhambra de Granada.

Mirador de San Nicolás, Granada. 21.01.

How should I describe it – coming home? I never lived in Granada itself, but between coming here at least three times before and a year living over the sierras to the west, this place feels… so familiar, compared to the other places I’ve been on this trip, anyway. The accent, the noise, the simple fact that the music playing over car radios as they pass is flamenco and not reggaeton… This is the Spain that captured my heart many years ago, when I was just a boy.

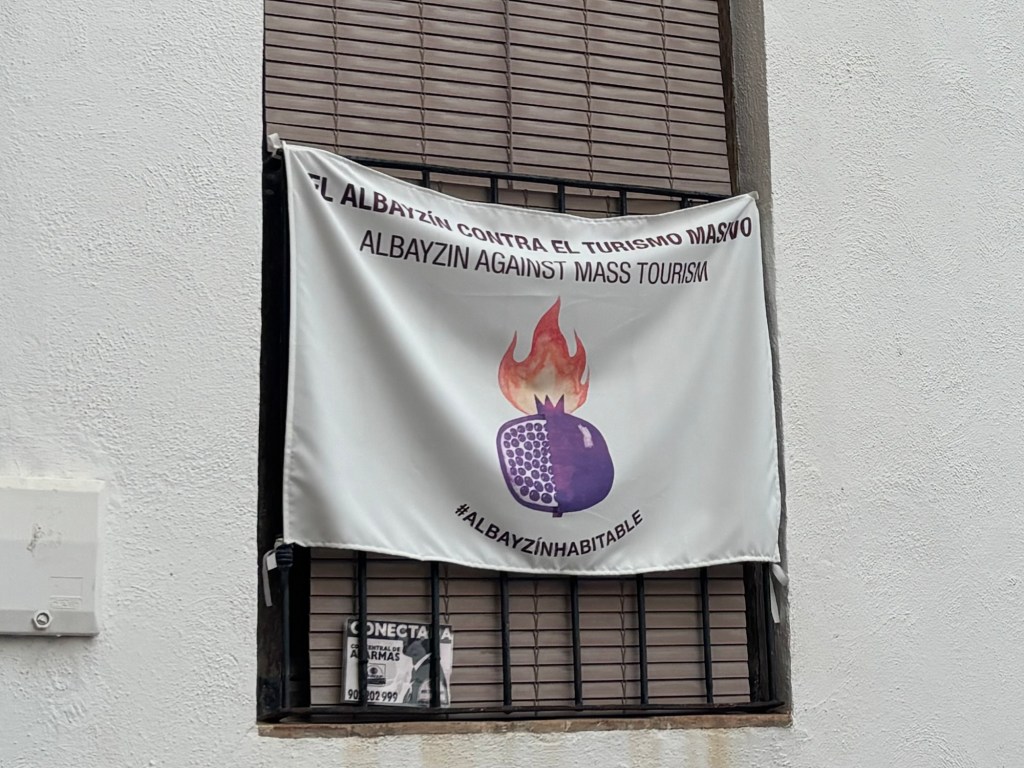

Things have changed since then, but not by much. There’s a lot of anti-tourist graffiti around, but then, perhaps I’m actively looking for it now. Here, in one of the most popular tourist destinations in Spain, that anger is directed at the American corporate AirBnB, an alternative accommodation method for the experience-minded traveler, which is currently being relentlessly advertised on TV with the tagline “don’t end up surrounded by a hotel”.

That’s all well and good, but much of Spain relies on the tourist industry to survive. In 2023, tourism accounted for an astonishing 12.3% of the country’s GDP, making it one of the most tourism-oriented countries in the world – and the numbers have only increased since then. Much of Granada, including Sacromonte – the formerly rundown gypsy neighbourhood beyond the city walls – has been given a makeover in the last twenty years to draw in as many tourist dollars as possible, and in its wake, a lot of the former pensiones – Spain’s traditional accommodation option, consisting of spare rooms rented out to travelers – have been replaced by glitzy “experience-oriented” AirBnBs. It’s an economy for the young and enterprising – or the international – and much of Spain simply can’t keep up. Adapt or die. And when the old ways are sacrificed on the altar of progress, some of the identity that made that place so special is lost. Eventually, even the tourists will realise this and stop coming, leaving these areas high and dry.

That’s why the phrase “AirBnB mata el barrio” (AirBnB kills the neighbourhood) is scrawled all over the place.

Fortunately, the magic of Granada continues to shine through the crisis. There might be a lot more of the American drawl on the street than there used to be, but it’s shouted down by the happy hubbub of the locals. Wandering along the Darro toward Sacromonte, I came upon a noisy group of youths on its banks, enjoying a picnic in the shadow of the Alhambra as their kind has done for centuries.

They weren’t too happy about a tourist family flying a drone nearby and threw a couple of colourful insults of the verbal and non-verbal kind at the buzzing menace as it passed overhead.

Sacromonte has hurled itself at the tourist trade as never before. Every other house seems to have decked itself out as a “tablao flamenco” where you can catch a live Flamenco show. Marketed as the “home of flamenco” – a title more appropriately applied to Sevilla’s Triana district, though the zambra certainly comes from here – Sacromonte was Granada’s former gypsy quarter, whose inhabitants lived in cave dwellings beyond the city walls since they were not permitted to live inside the city.

The heat of the summer is one reason they retreated into the rocks, and the zealousness of the Spanish is the other: this “pariah district” served to accommodate the unwanted, the unclean and the un-Christian – which amounted to the same thing for much of Spanish history. It even housed some of the city’s Jewish and Muslim population following the fall of Granada in 1492, as they were gradually driven out of the city by the conquering Christian warlords.

When my mother came here in the 1980s, this was not really a district you’d want to find yourself in after dark. Nowadays, that’s precisely the time the locals want you around, as that’s when the flamenco shows take place. I’m still considering whether to check one out. I’m hoping for something authentic, but I feel that star may have descended a long time ago.

Up above, the Mirador de San Nicolás remains as busy as ever at sunset, with throngs of in-the-know tourists and locals waiting to see the spectacle of the Alhambra and the Sierra Nevada beyond bathed in red light. It was cloudy tonight, so a few of them ambled away disappointed. That at least meant I snagged a spot on the wall to sit and draw the mountains for a while. I didn’t take the camera. No need. I got the “famous” sunset photos years ago, and besides – there’s a fair bit of ugly scaffolding on the Alhambra now that wasn’t there before.

The Mirador de San Nicolás is a funny place. I imagine it’s raved about in all the guidebooks as the secret is most definitely out. There’s still a bunch of musicians here plying their trade as there were ten years ago, asking for “collaborations with the music” on the back of the guitar after every song. They’re not quite as tuneful as I remember. The men had a fair amount of duende but the girls singing along were absolutely tone deaf, which took away from the magic a little.

But not as much as the large number of folks on the wall with their backs to the Alhambra, staring gormlessly at their phones.

I must have been there for at least half an hour, because when I was finished sketching the moon was up, the Alhambra illuminated and the city lights twinkling away in the gloom of the vega below like velvet. I relinquished my spot on the wall and set off for my pensión.

On my way back, I was stopped by the piping call of a scops owl. I haven’t heard one in years, nor seen one even once, for that matter, so I set out to track it down. They’re master ventriloquists, especially in a city of infamously winding streets where their voices seem to come from all directions at once, but I did manage to follow its call to the Placeta Cristo Azucenas, where I spotted the diminutive creature as it took flight as a noisy van hurtled past. Hopefully I’ll see it again before my time here is up.

Well, it’s now 8.23am of the morning after. I’d better head into town, find a laundromat and get some breakfast. I’ve got a lot of things to see and do today – not least of all, the Alhambra herself. BB x