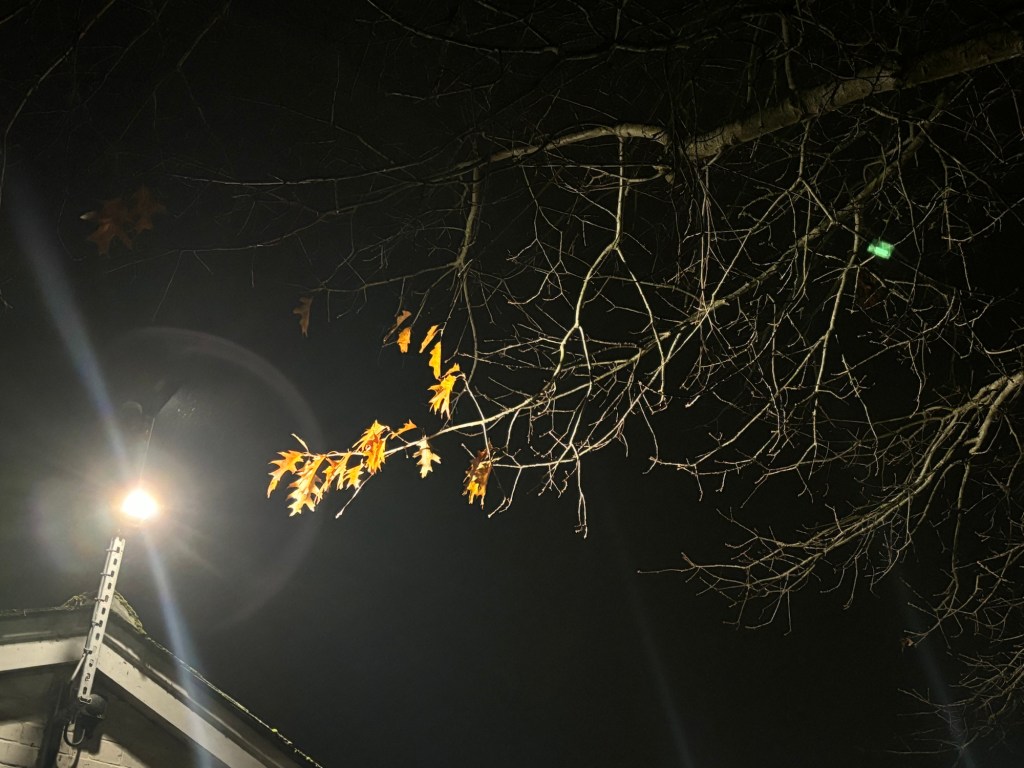

There’s a small oak tree that grows beside the boarding house. It shed its leaves a couple of weeks ago, briefly covering the tarmac in a golden-brown carpet, before the groundskeepers swept them all up into the back of a truck and took them away to the tip. A beautiful gift of death tossed into the trash. Word must have got around, in that silent way that trees have, as so many of the trees around the school have since held jealously onto their leaves well into the usual falling season. My oak, stripped to the skin, looks cold. Winter will soon be here and it has lost its coat.

The world seems a little darker right now. It’s not just the longer nights. The news is full of it. Abuse in the Church of England. Treachery and death in the Middle East. A self-confessed day-one-dictator returning to the White House. Politicians who once laughed at the Man spinelessly throwing in their lot behind the future power base. Shadows creeping over Ukraine. I expected to see more of it on my social media feed, but there’s been surprisingly little said about the US elections. Perhaps the folks I know have listened to the voices in the wind and decided that now is not the time to voice their concerns online. Perhaps they vented their frustration elsewhere. Or perhaps – and I suspect this to be the grim truth – most of them just didn’t care overmuch.

There’s a quote often attributed to the Anglo-Irish philosopher Edmund Burke that runs along the lines of ‘evil triumphs when good men do nothing’. As is the way with so much these days, there’s almost no evidence that he actually said such a thing. We have learned to doubt everything. In that light, how can you blame a nation for putting their confidence in a self-confessed liar?

Burke did, however, say something similar, albeit a lot more profound:

When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle.

Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770)

He might have been writing a little over two hundred and fifty years ago, but he might just as well have been describing the world as it is today. It is always rather chilling when the voices of history stretch their pale and clammy hands into the present.

Until we learn to put our differences aside and work together – even with those with whom we do not, cannot or simply will not see eye to eye – our future will be in somebody else’s hands. Until the educated West accepts this reality, there will be no end to the head-scratching and the bewilderment. I have beat upon this drum since my schooldays, where it was doubtless drummed into me by my teachers, but I still believe this to be true: that you should always be prepared to listen and engage in conversation, no matter what you believe. Cancel culture does not work. It just fans the flames of those who feel their needs are being ignored and their voices silenced. We are marching into an increasingly intolerant age, and it worries me that those who fight for tolerance’s sake are among the vanguard, whether they know it or not. Men like Trump ride into power on the backs of such virtue-signallers.

I’m reading my way through a number of books to try to see the world through somebody else’s eyes. It’s my way of dealing with the situation – particularly when my profession is to help children to make their way in the world. I’ve started with Douglas Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe in an attempt to understand the growing immigration frustration in my country (having been an immigrant myself, however briefly). Ilan Pappé is in the wings. I can’t say I agree with everything I read, but it’s broadening my perspective a little more, and that’s no bad thing.

In the spirit of remembrance, they read the list of names of former students of the school who lost their lives in the two world wars in front of the war memorial yesterday. All of the numbered fallen had one thing in common: not a single one had died on the field of battle. Died in a collision during training. Run over by a lorry near base camp. Killed by an explosive during a training exercise. Shot down by friendly anti-aircraft fire after returning from a successful mission. The senseless waste of war was never more plain. When I was younger I had the morbid suspicion I would see another such great war in my lifetime. It was only ever a whimsy, but these days I am not so sure.

Some of the students were dressed in their military uniform. I had a grim vision of a towering cenotaph. Etched into the cold marble slab were names from every corner of the globe. I hope it does not come to that.

On closer inspection, my little oak has not lost everything. Not yet. A few golden leaves have held onto life, a full fortnight after the rest bowed to the inevitable. It just so happens that they are growing on the branch that reaches closest to the light. I wonder if that is what is keeping them alive.

We can’t give up hope. Hope is one of the things that makes us human. As winter draws near and the world darkens a little more every day, remember to hold on to the light in whatever form that takes for you. It is a warm and precious thing. BB x