No two days are the same when you’re a teacher. It’s hackneyed, but it’s true: children are infinitely more changeable than tired and heavily programmed adults, whose desire to rebel and create has usually been all but eroded by the necessities of everyday life. That being said, I guess I expected at least a modicum of routine when I answered the call to become a teacher. How wrong I was… and what a couple of years it’s been!

Two years and two months ago (almost to the day) I remember sitting in my living room with my housemate with the radio on, listening to the Prime Minister’s national briefing. Perhaps you remember it – it was the one where he officially announced a national lockdown in the wake of a sudden surge of COVID-related deaths.

It’s eerie to think how little attention we paid to the scourge of the decade back then. You could certainly argue that when Trump called it the Chinese virus he was only echoing what a great many people were thinking at the time. When I left for my placement school in late February COVID was little more than a minor article concerning the city of Wuhan. When I came back to work three weeks later I had to reprimand a student for refusing to sit near a Chinese classmate. If you want to get a feel for how it felt back then, read John Christopher’s 1956 apocalyptic novella The Death of Grass. Without giving away too much of the plot, it centres around a disease which originates in China (where it may or may not have been engineered) which leads to the starvation and death of thousands of Asians, but does not cause any genuine panic in the West until it arrives on their doorstep a few months later. The parallels are more than a little alarming.

Then came Boris’ address to the nation and the closure of schools – more than a week after other businesses had been ordered to shut up shop. Our kids had already been sent home a few days prior, so I suppose it wasn’t entirely unexpected, yet all the same, I remember thinking we might just make it to the end of the week and the Easter holidays before the portcullis came down.

I was wrong.

For the rest of the summer, I taught my lessons online. Those of us who had been reluctant to shift our practice into the virtual world were given a violent kick into the future. Google Classrooms replaced real classrooms as we moved everything online: first to Google Hangouts, then to Google Meet. The constant low hubbub of the classroom vanished, to be replaced with the two-tone jingle of Google Meet’s “hand raise” feature.

Some students – perhaps at their parents’ request – kept their cameras on at all times, but most disappeared behind their initials or a selected profile picture of this or that image lifted from Google. I caught myself consciously staring out the window and trying to focus on objects in the middle distance as my eyes began to ache from the strain of staring at a screen all day. Exams that might have taken an hour to mark took all afternoon. I tried to keep an eye on all twenty-odd tabs I had open so I could monitor my students’ work, knowing full well that even in a real classroom I couldn’t possibly expect to teach a lesson whilst eyeballing every workbook simultaneously. Saturday school was cancelled, but by the time Saturday came around I only really had the energy to collapse.

As the summer drew to a close and some staff and students returned to the site for a phased return, I remained at my post on the other side of the south, giving mum moral support as she fought to keep her school alive and counting down the days until I could unplug from Google for good.

When we returned in September, it was to a school that had to learn to live with COVID. Social distancing put a definitive end to any interaction between year groups – and, by definition, sporting events and music (singing was outlawed anyway). Lessons were necessarily cut short because of the need to wipe desks down between classes. Students kept to their zones and teachers moved from place to place, as though we’d given the finger to Brexit and decided to follow the European model. The whiteboards were often unusable due to the constant application of hand sanitiser, and more than ever, I was teaching through PowerPoints and digital workbooks – and falling increasingly out of love with both as a teaching method.

Most of my friends who weren’t in teaching were either working from home or operating in new, post-Covid systems that had them in the office three days out of five. We didn’t see changes that drastic in teaching, to be honest, with most families calling for a return to normality for the sake of their children’s mental wellbeing. Be tolerant. Be understanding. So we plodded along, tolerant and understanding. Some people followed the rules about social distancing to the letter. Some didn’t. Invariably, where they didn’t, outbreaks followed.

And while we dealt with the outbreaks as they came – usually by sending classes or year groups home one at a time – we had to deal with an increase in power outages, too. For whatever reason, we were hit by a real spate of them as we hurtled into the second lockdown (and in a genuinely absurd divine prank, one has literally just hit as I was writing this… never mind hindsight, this is just plain spooky). Power cuts meant no internet, and no internet meant no lessons (or email, for that matter). So while “snow days” were forever killed off by the invention of remote learning, the common power cut took its place.

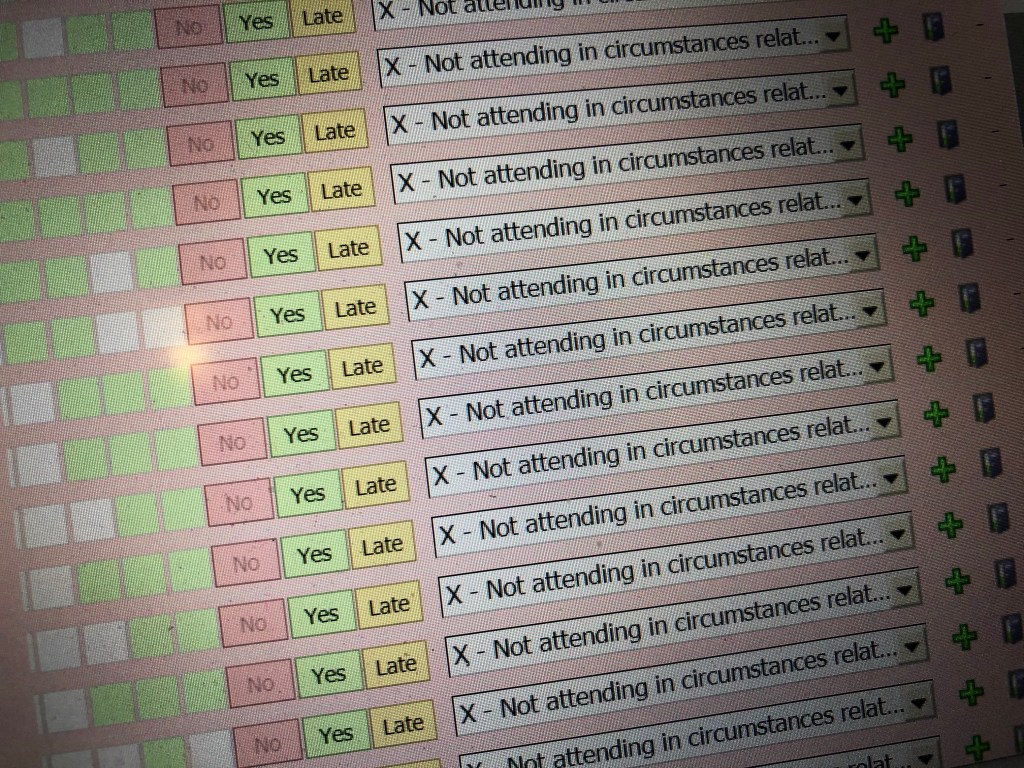

The second lockdown was more tedious than the first: stripped of its novelty, most of us were just waiting for the all-clear. And when we did return, there were so many things to keep an eye on. Which students were on RPDs (Remote Pupil Device) this week? Which ones weren’t (they needed work sent to them instead)? How did you balance your teaching to make sure the ones on the screen were getting your full attention, when the other twenty-odd sitting in the classroom also required the same?

Boarding was even more complicated. Over the course of the year I played teacher, counsellor, test-and-tracer, secretary, waiter, cook and delivery boy. I donned plastic gloves, apron and a face shield and took temperatures with a gun-shaped thermal detector. I took my isolators for walks – codenamed “fresh air” – after putting the others to bed, so there was no risk of them contaminating others. More than once I wondered what this boarding school malarkey would be like without all the myriad responsibilities that living with Covid thrust upon us all.

September 2022 began on a much more hopeful footing. Many of the previous year’s trials remained, such as the boarders’ test-to-fly hurdles and the itinerant disappearance of this or that student from the classroom (for a period of no fewer than 14 days – then 9, then 3). However, as winter turned to spring and a third national lockdown looked about as likely as a white Christmas, we breathed a collective sigh of relief. The jabs had done their job – or rather, the moral panic had abated with the knowledge that more than half the nation was now triple-vaccinated against the menace. Covid became a cold: more of a nuisance than a threat.

If truth be told, I’ve probably forgotten many of the day-to-day details. Things have changed so much over the last two years. With school exams now back in full swing, I’d even go so far as to say that it’s only in the last three weeks or so that things have finally returned to normal – whatever that was.

Over the last week I’ve been asked to support no fewer than three overseas school trips planned for the next academic year. This week alone we bring the summer half term to a close with a practice expedition for the Duke of Edinburgh students, a summer concert in the Abbey, our first Sports Day in three years and a Speech Day that we’ll be able to attend in person, rather than in tutor groups via a Google Meet link. It’s taken a long time, but in the grand scheme of viruses and plagues and diseases, we’ve bounced back incredibly quickly.

I had a great time today standing in as a very willing target in the “Throw a Sponge at the Teacher” stall at the Sixth Form dog show, but more than anything else, I was over the moon to see so many students, staff and parents back on site, mask-free, mingling as though the last two years never happened. Fear did not get the better of us, and we have come out the other end smiling.

I’d still recommend John Christopher’s novel for a dose of reality, if only to cancel out the hubris high I’m feeling right now – because his message is no less relevant now than it was over sixty years ago – or even two years ago:

The scientists have never failed us yet. We shall never really believe they will until they do.

John Christopher, The Death of Grass