There’s a day in the second or third week of January that, at least in these cloud-ridden islands, marks the turning of the year. Not the first day of spring exactly, but an early harbinger that the dark days of winter are finally on the retreat. For me, it’s always marked by the first real blast of birdsong, and it usually goes hand in hand with a generous glow of sunlight after many days of cloud, or that infinite whitening of the sky that is so very well-known to those of us native to this rock. There’s no calling when exactly that day will fall, but when it does, it’s nothing more or less than exactly what the doctor ordered, as far as I’m concerned. I grab my journal and keys, leave the flat, walk up to the office and – boom. There it is. The dawn chorus is already in its final movement, but still going strong. The voices of robin and blackbird and woodpigeon and sparrow lift my heart skywards. I’m then in an irrepressible good mood for weeks which neither marking nor duty nights nor even thunder, rain and storm can stamp out.

I guess I can only apologise to my colleagues for the nauseous wave of positivity that nature washes over me. It’s almost first-year-of-university-level enthusiasm (which, for those of you who knew me then, you know…).

Perhaps spurred on by that wintry magic, I made two random throws this weekend. I bought a kite, and I decided to re-read one of my favourite childhood stories. The kite is easy enough to explain. I had a kite once, when I was a lot younger, which has Jeremy Fisher emblazoned on its face. If I remember correctly, it didn’t fly very well. I guess we never tried it out on a day when the winds were good. It just seemed to gather dust in one of the cupboards until, one day, it disappeared. Anyway, I’ve got the whimsically romantic notion in my head that kite-flying is one of those things I’d love to do with my kids someday, so I ordered one on that whim. It arrived yesterday, and if I get a moment’s peace this week, I’ll put it through its paces out on the South Downs.

As for the reading – alright, I confess, I didn’t do any reading per se. I had a fair amount of spring cleaning to do, but I wanted a soundtrack while I worked and I figured an audiobook would be just the ticket. I’d had Michelle Paver on my mind after dipping my toes back into her ghost stories a few days ago, which naturally conjured up memories of reading her Chronicles of Ancient Darkness series when I was at secondary school. I remember absolutely adoring the first in the series, Wolf Brother, and motoring through at least the first sequel through my school library. I cannot remember exactly whether I made it as far as Soul Eater, the third in the saga – if I did, I forgot the plot more completely than that of the second – but I remember the books rising out of a videogame-clogged adolescence like icebergs, one of precious few literary stepping stones across a goggle-eyed, pixelated river that ran at full strength for far too many years. Was it Paver’s intense attention to the natural world in her writing that hooked me? Probably. She is one of my favourite authors for precisely that reason: she knows her settings as though she has lived within them her whole life through.

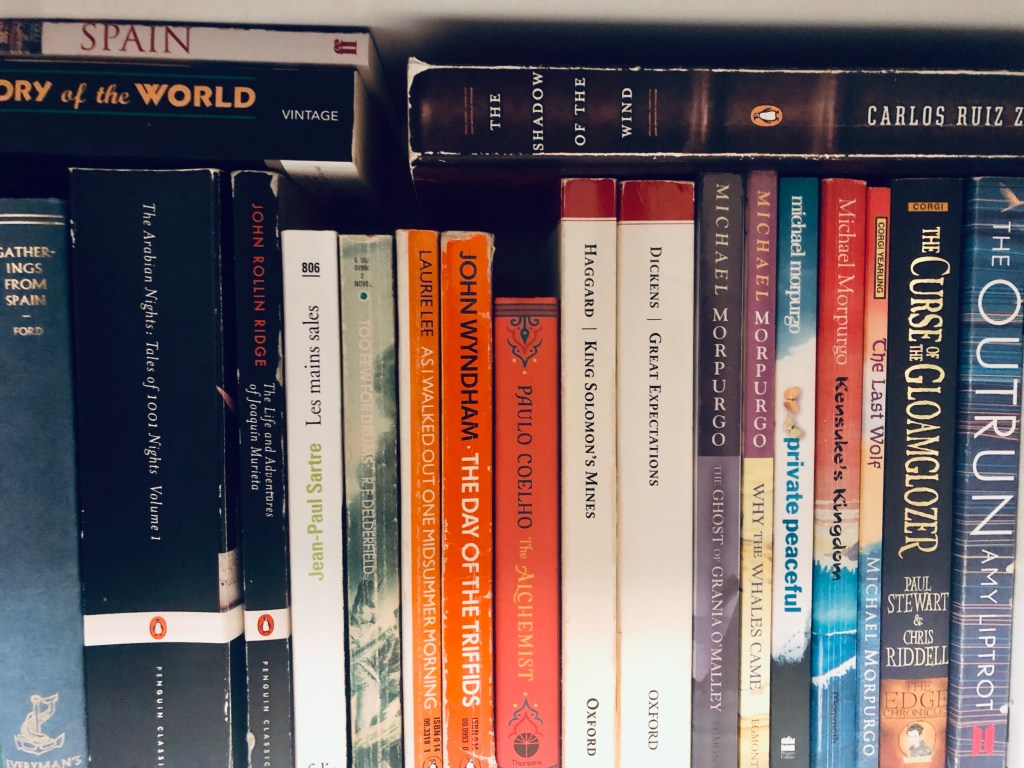

Wolf Brother had a lasting impact on me as a writer, more than I had previously suspected, and it took listening to the masterful narration of Sir Ian McKellen over the weekend to realise just how deep the roots of her magical storytelling stretched into my own creations. Naturally, my own stories have changed a great deal since I started writing them over twenty years ago, but if you look closely, you can see the tell-tale brush strokes of the authors who showed me the way. I could fire up my hard-drive right now, pull up a folder, pull out a chapter and point out the guiding hand of this or that storyteller. Here is some of Paver’s naturalism, and there’s some Rider Haggard gung-ho. Paul Stewart and Chris Riddell had no small part to play in the healthy dose of tragedy, and I’d wager a fair amount that there are traces of Michael Morpurgo spread throughout like watercolour, since at a certain point in my childhood I pretty much read nothing else. There was just something about his writing that spoke to me like no other writer could. He had me hooked on all his animal-centred storylines, his Scilly Isle adventures, and his occasional reference to something on my wavelength (like namedropping The Corrs in Arthur, High King of Britain). Kensuke’s Kingdom and Why the Whales Came rank near the top, and sit in pride of place by my desk alongside the other books that mark certain turning points in my life: Day of the Triffids for traveling solo, King Solomon’s Mines for going mad in Amman, The Arabian Nights from my university days and The Outrun for a dose of reality when I left that world behind… and The Tale of Benjamin Bunny… just because.

What were the stories that had the biggest impact on you as a child? Which authors colour your writing? I’ve ended the last couple of posts with a question, which is a) repetitive and b) pedantic and c) a sign of how much I’ve been teaching and how little I’ve been writing these past three years. But it’s something I love to ask people, when I get the chance. The power of storytelling has been precious to me since I was a bratty kid insisting on the fifteen-minute bedtime stories and not the three-minute tales (I swear I wasn’t just looking for an excuse to stay up late…!), and I hope it’s a joy I can share with my children someday.

When you come back to a book you enjoyed as a child, you see it through two pairs of eyes and two hearts: the eyes of a child embarking on a journey as though for the first time, and the eyes of a parent who knows the dangers ahead but cannot help hoping things turn out for the best. It’s incredible how the magic contained within the pages of those stories never fades, no matter how many times you come back to it. I make a point of re-reading Triffids every time I travel alone, but I’ve neglected the stories of my childhood for too long.

Once I’m done with the rest of Torak’s adventures, you’re next, Morpurgo!

BB x